The void and the infinite

The mysterious Lagos Handbook, Rem Koolhaas, and Doxiadis Associates

This post is an excerpt from an article I published in the 2024 volume “Adaptive Cities?” from the Associazione Italiana di Storia Urbana (AISU), based on a paper I presented at the AISU conference in Turin, 2022.

It is unusual to read an enigmatic master’s thesis and come across the parody image of a Pokémon-esque trading card game depicting a “globetrotting planner.” The portrait on the trading card consists of Constantinos Doxiadis, an influential Greek city planner. The game is called “Big manTM.” On the card, Doxiadis’ “powers” include high levels in diagramming, urban design, and infrastructure, an average ability at “nation building,” but possessing a “diagram bonus.”

Doxiadis, despite being active in thirty-plus countries from 1953 to 1975, is an historically under-appreciated figure in modernist urban history. The efforts of Doxiadis and his firm have only recently begun re-evaluation in urban studies conferences and journals. For Doxiadis to appear so bizarrely as a figure in a fictional trading card game, in a book about Lagos shaped by the guiding hand of another star architect, demands further scrutiny.

That curious text is available to be read at the Frances Loeb Library of Rare Books and Special Collections at Harvard University, and it is titled The Lagos Handbook, or a brief description of what may be the most radical urban condition on the planet. The volume is anything but brief—it runs some 612 pages, with seven maps and 193 drawings. Crafted as part of the Harvard Project on the City, the effort was submitted as a master’s thesis for the project’s participants at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, under their faculty advisor, Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas.

Within architecture and design circles, The Lagos Handbook has taken on the status of a myth. One blog entry on Archinect by Quillian Riano enigmatically stated, “As far as I know there are only two copies, one in the GSD’s Loeb Library main collection and one in the GSD’s special collections.” On another thread of Blogger, Riano posted, “I wonder what’s up with that book, even the librarians at the GSD laugh when I ask if they have any insider knowledge.” Another respondent on that thread, Nate Slayton—one of the credited authors of The Lagos Handbook—wrote, “The single copy in loeb’s special collections is likely the extent to which it will ever be broadcast.”

In fact, the Lagos Handbook thesis was the basis for a book called Lagos: How It Works, scheduled for publication in 2008, its listed authors Koolhaas and Edgar Cleijne. According to an interview in The Guardian, Koolhaas explained that in the end, the adaptation of the thesis was not pursued due to political correctness. “There’s an old school of thought that somebody like me has no place to go [to Lagos],” Koolhaas said. “Because of that innuendo, in the end we didn’t publish… it was the first manifestation of what is currently a really big issue: how political correctness defines the limits of what you can do.”

However, sections of the Handbook were repurposed and adapted into a section on Lagos in Mutations, a publication that accompanied a 2000 exhibit in Barcelona. A 55-minute documentary directed by Bregtje van der Haak, Lagos Wide and Close (2004), was re-released in 2014 online. But most of The Lagos Handbook, as Slayton iterated, sits in the Loeb Library for the curious researcher to stumble upon.

Other writers, such as Kostas Tsiambaos, have previously linked the ideas of Koolhaas to those of Doxiadis. Granted, the Harvard Project on the City was not the effort of one personality, but several. But the involvement of Koolhaas is interesting, particularly since few contemporary figures in architecture and planning have sought a connection to or dialogue with Doxiadis.

The Lagos Handbook’s admiration for Doxiadis’ theoretical work in relation to Lagos and the idea of the megalopolis indicates an intellectual influence on the thinking of the Harvard Project on the City, and on that of Koolhaas himself. Since the 1980s, architectural theorists have become suspicious of modernism and its neocolonial undertones. Koolhaas has elsewhere argued (and lamented) that the discrediting of modernist city planning as a profession has ironically come at a time in history when neo-modernist planning studies might have utility.

The Lagos Handbook

The copy of The Lagos Handbook in the Loeb Library entertains a far-ranging breadth of topics—from ethnographies of the Oshodi market, to the informal lake-bound settlements of Makoko, to the phenomenon of oil company “compounds” for wealthy expatriate contractors. Taken altogether, The Lagos Handbook is a truly dizzying opus of seemingly limitless proportions—fitting, given its object of study is the eponymous Nigerian megalopolis, whose metro area in 2021 enumerated a population of over 14 million. Such a book’s argument is hard to assess, but its epilogue spells it out:

A pressure cooker of scarcity, extreme wealth, land pressure, religious fervor and population explosion, Lagos has cultivated an urbanism that is resilient, material-intensive, decentralized and congested. Lagos may well be the most radical urbanism extant today, but it is one that works. This book is an account of the convergence of extreme conditions, the consequences and adaptive responses of urban form at the leading edge of globalization.

The book follows the house style of Rem Koolhaas and his Office of Metropolitan Architecture, its presentation evoking the avant-garde images and large print of his classic doorstop compendium created with Bruce Mau, S, M, L, XL. The handbook opens with a provocative slideshow featuring images of Lagos’ dizzying sprawl against the text of various luminaries, Western and African (but mostly Western), to reflect on the Nigerian milieu. The quoted figures include Joseph Conrad, Paul Theroux, Bill Clinton, Graham Greene, Robert Kaplan, and Chinua Achebe. The first slide—juxtaposing a map of Nigeria with a quote from a 1996 article in the Houston Chronicle—certainly sets the tone. It reads, “The most corrupt nation in the world.”1

In citing so many colonial authors and 1990s-contemporary elites, the text makes the effort to indicate it is the final word on such omniscient declarations. Lagos, in its view, is a form of hell, but, against all odds—it works, apparently. There is also a teleology to the narrative in The Lagos Handbook—that Lagos is an image of the future of all cities, of all mega-regions, the ultimate product of globalization and the capitalist system. As Lagos became Nigeria’s primate city, it monopolized the economic growth of the country, driving more and more low-income arrivals from rural areas searching for jobs that didn’t always exist, a desperation driving the growth of informal settlements and marginal forms of employment. In that way, the reality of Lagos has a lot in common with Doxiadis’ idea of ecumenopolis, the theoretical city that, in his view, would one day encompass the entire globe due to unchecked population growth.

Constantinos Doxiadis and Doxiadis Associates in Africa

Headquartered in Athens atop Lycabettus Hill, Doxiadis Associates (DA) was best known for its master plan of Islamabad, the capital of Pakistan. But during the firm’s apex from the 1950s to the mid-1970s, it was involved in hundreds of projects, in more than 30 countries, most notably in the firm’s work for a housing plan in Iraq, a master plan for the state of Guanabara in Brazil, and a study projecting a “Great Lakes Megalopolis” centered around Detroit, Michigan.

Central to DA’s organizational mission was Constantinos Doxiadis’ design philosophy of “Ekistics,” the science of human settlements. Coined from the Greek word for “settling down,” ekistics in practice was an early form of interdisciplinary city planning, with its own language and methodologies. The ideology formed the intellectual backbone of Doxiadis’ constellation of related organizations based in their shared office complex in Athens—a think tank called the Athens Center for Ekistics, degree-granting institutions such as the Athens Technological Institute and the Graduate School of Ekistics, the Ekistics journal of planning, and the Delos Symposia, a conference series on human settlements held on a cruise ship which sailed the Aegean every summer. Doxiadis also wrote many books to develop his ideas, from his textbook Ekistics: An Introduction to the Science of Human Settlements to Ecumenopolis: The Inevitable World City. These texts represented an interesting precursor to Koolhaas’ similarly ambitious publications

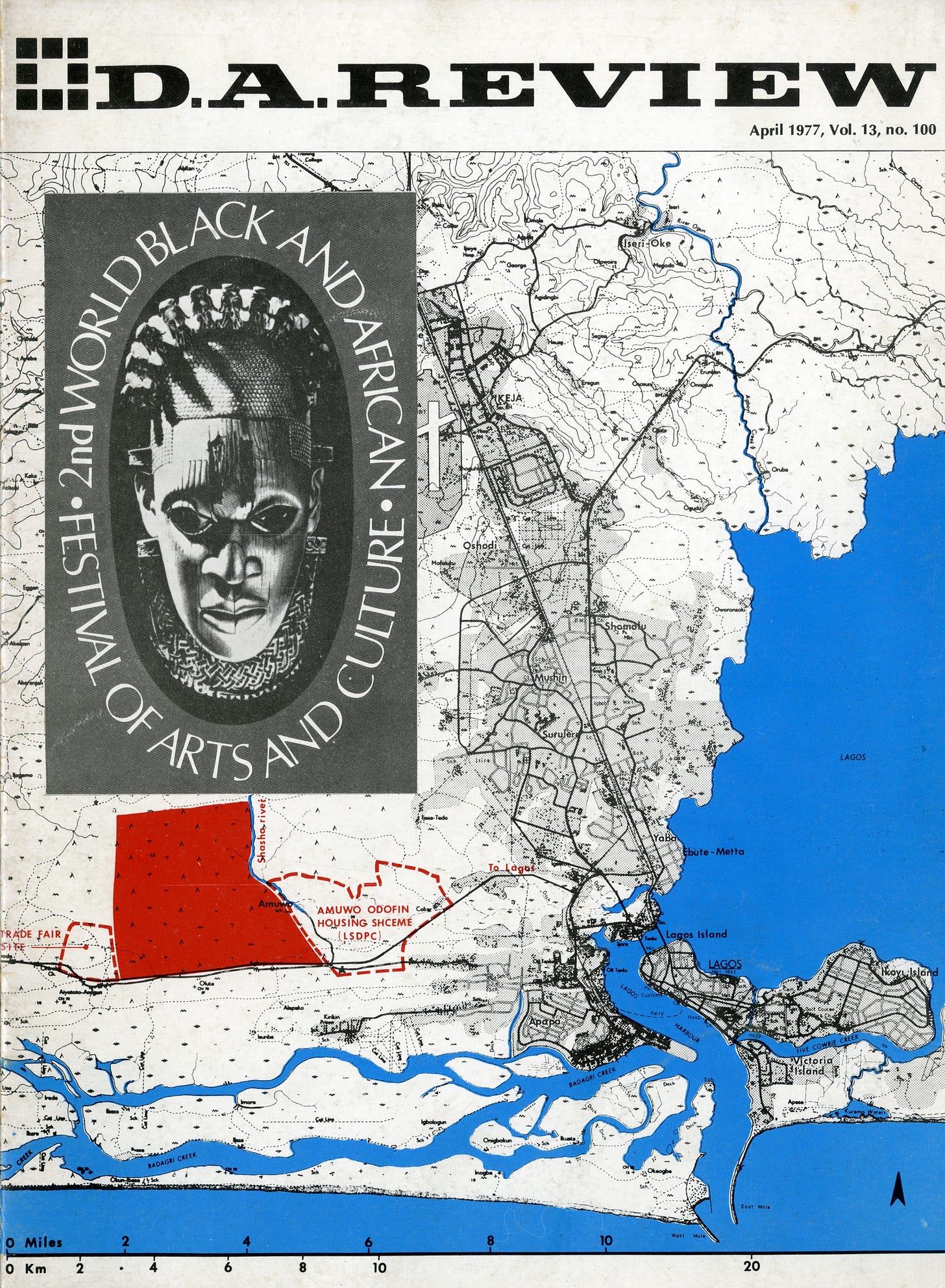

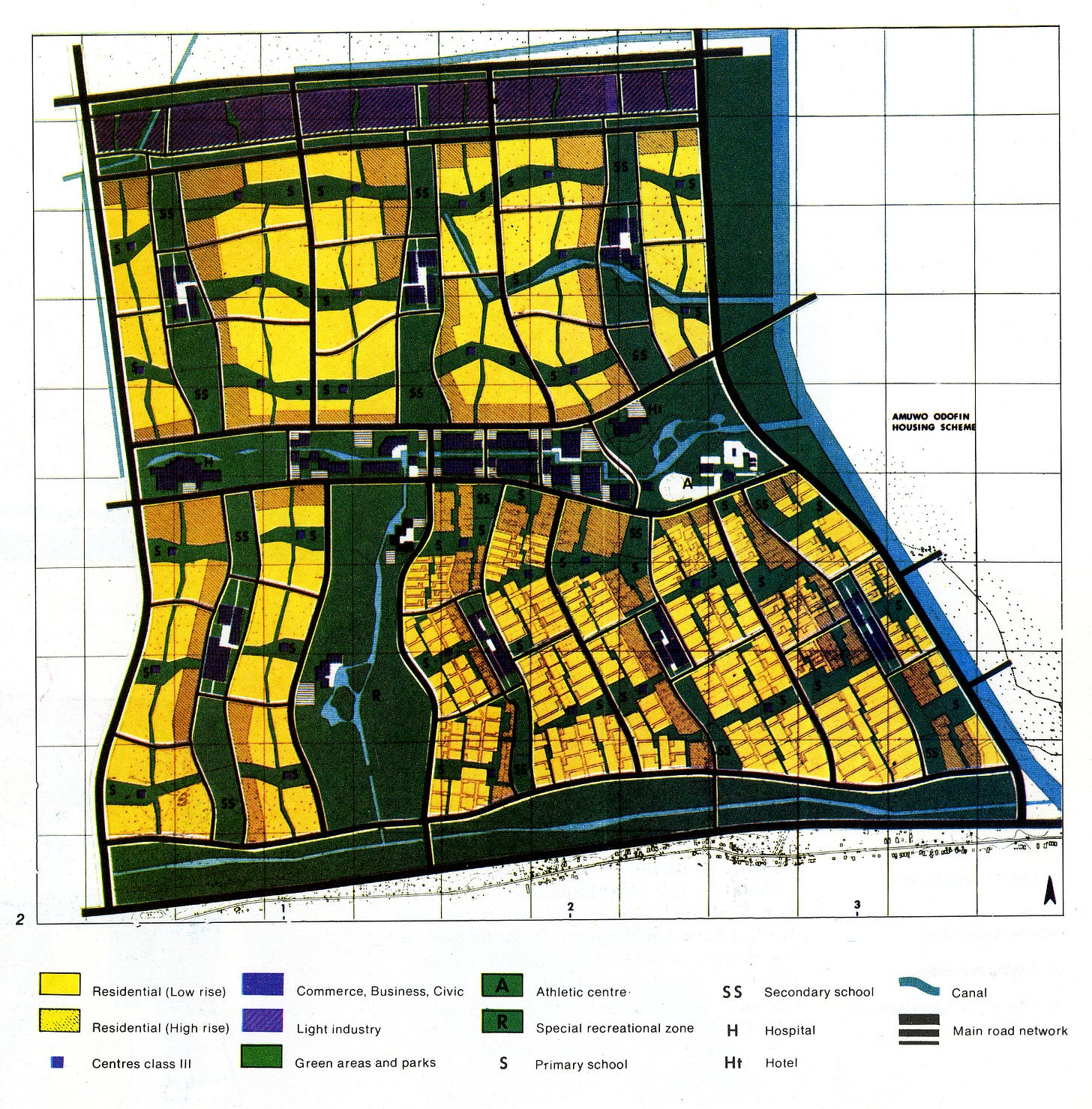

In Africa, DA conducted projects of varying extent in Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Sudan, Ethiopia, Somalia, Ghana, Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo), Zambia, and Nigeria. The work in Tema, Ghana comprised one of the firm’s most significant projects on the continent. In Nigeria, DA’s involvement began in 1972, when they produced development plans for twenty urban centers. This led to master plans for the Black Arts Festival Village (also known as FESTAC), a master plan for the city of Illorin, the capital of Kwara State, the master plan for Jos-Bukuru, capital of Benue-Plateau state, and master plans for a series of towns, including Eket, Etinan, Opopo, and Oron.

In one of the most comprehensive retrospective volumes of Doxiadis’ career, Alexandros-Andreas Kyrtsis cautioned that attributing Doxiadis’ singular vision or intent in his Nigerian projects was a flawed prospect, given Doxiadis’ death in 1975 of ALS and his declining health in the lead-up to his passing. The Lagos Handbook added: “It is unclear whether or not Doxiadis actually spent any time in Lagos, because of a conspicuous absence of his usually excessive documentation of site visits.”

But Doxiadis’ practices were well-established at his firm by this time, and though the firm was sold and substantially restructured after his death, for several years afterward his associates carried on with his design ethos in his absence. Moreover, even though his Nigerian projects didn’t officially begin until 1972, he began writing about Africa in the 1960s, a point that The Lagos Handbook authors raised to justify his inclusion in their work.

Read the rest of the essay, originally published by AISU, here.

This is the fifth essay in The World Planner series, chronicling my biographical investigations into the life and times of Constantinos Doxiadis. These pieces take longer to write than the other posts, so they’ll appear on an intermittent basis.

If there are stories you would like to share about Doxiadis for inclusion in my work, please write to me at doxiadisbiography[at]gmail.com.

Perhaps these pronouncements account for the “innuendo” that Koolhaas alluded to, precluding the publication of the Lagos Handbook.