When we think of global cities we often think of architectural landmarks—Big Ben, the Eiffel Tower, the Golden Gate Bridge. These architectural idioms often act as visual metaphors for the cities at large, serving as tangible examples of cultural heritage.

But cultural heritage doesn’t have to be physical. Just ask Shakespeare. In his play Coriolanus, the bard wrote, “What is the city but the people?” Indeed, sometimes cultural heritage is intangible, invisible for 90 percent of the year.

That’s certainly the case in the Cypriot city of Limassol, where the city’s rapid growth amidst a scandalous high-rise building boom has produced something of an identity crisis—a humble fishing village in the 19th century has, in 2024, found itself the small island nation’s answer to Dubai. And despite the city’s unchecked growth and constantly shifting demographics, there’s one unique aspect of Limassol that has unified the city: the city’s annual celebration of Carnival.

In 2022, when I gave a presentation on competing visions for the image of Limassol at a Cypriot museum, I discussed the initiatives of several architects and intellectuals discussing their plans and ideas for Limassol’s future image, all attempts to bring order to the built environment’s chaotic state.1 But I had the good fortune of meeting Stelios Georgiades, a Cypriot diplomat who spent 14 years writing the definitive book on the Limassol Carnival (ΚΑΡΝΑΒΑΛΙ ΛΕΜΕΣΟΥ: Μια μαγική ιστορία, 2016). Georgiades explained to me what my analysis was missing—an evaluation of the heritage that couldn’t always be seen, and yet has been present for hundreds of years.

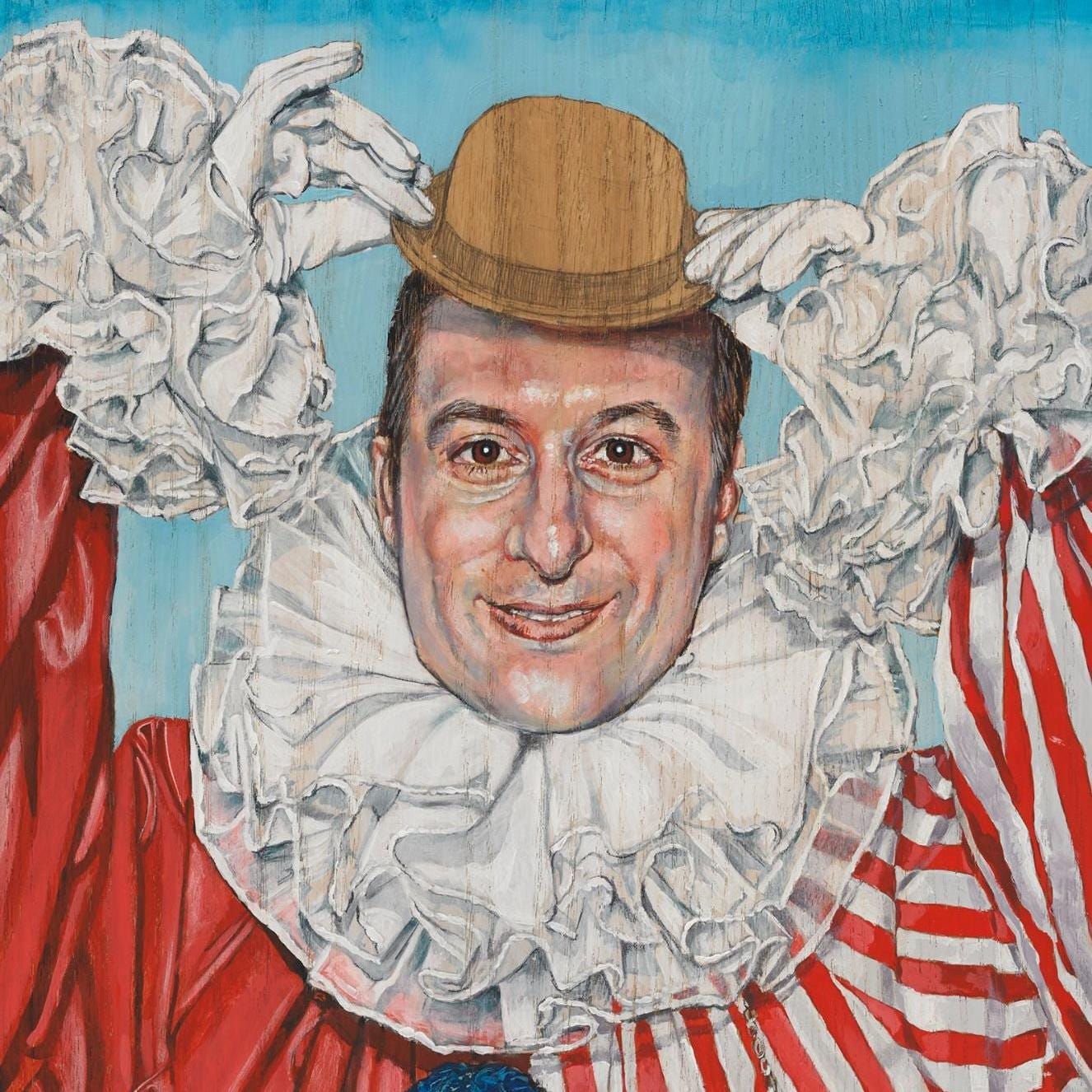

While some go as far as tracing Limassol’s carnival to an ancient festival of Dionysus, a more likely origin is the influx of Catholic Europeans during the Crusades and later Venetian rule on the island, when the French and Venetians brought their pre-Lenten festival to the island. Though Limassol’s Carnival is celebrated by a majority Greek Orthodox population, it has a lot in common with the Mardi Gras in New Orleans and Rio de Janeiro’s Carnival celebrations—featuring parades, masked balls and parties. “In the past, people could not travel,” Georgiades said. “Carnival was like the window to something different, something more exciting.”

A work of oral history, Georgiades’ book preserves the memories of multiple generations of Limassol residents. To Georgiades, Limassol’s Carnival is an example of what UNESCO calls “intangible heritage,” local traditions passed down from generation to generation.

Other examples of intangible heritage, per UNESCO, include Syrian glassblowing and Switzerland’s pasture culture. “You cannot touch it like a building,” Georgiades said. “You cannot preserve it in the way you preserve a building.”

After centuries of celebrations, carnival achieved a resurgence in the early 20th century, when British rule spurred industrial development in Limassol, and the festival facilitated social mixing between classes—the well-to-do mixed with the working class, sex workers, and British sailors. The carnival acted as a mechanism for social fluidity, and sexual and gender fluidity as well.

“The carnival gives a sense of pride for all these people,” Georgiades said. “Pride of their town, a connection of a group. It builds an identity… [of] being very artistic and creative.” The carnival has also earned Limassolians a nickname in Cypriot Greek: The Crazy People. “It’s considered a compliment for the people of Limassol, a title of honor to be called crazy,” Georgiades added.

The Limassol Carnival’s annual revelries, masked balls and costumed parades are an annual tradition and expectation. When the city canceled its parade in 2021 and 2022 to meet the country’s stern COVID measures, Limassolians organized their own unofficial celebration.

“You could feel that there was an unease, quiet, and I felt that it was going to explode,” Georgiades recalled. He explained that a former carnival queen organized a parade of cars on the main Limassol avenues as a makeshift celebration. “There were like thousands of cars in the streets.” Many of them were festively decorated, their drivers honking and passengers shrieking for joy. Naturally, a large number of the revelers ended up gathering on the coastal road, causing chaos and violating covid restrictions. “Carnival could not be forbidden, not even in the most strict days of the pandemic,” Georgiades said. “It’s an anarchic town.”

With its cosmopolitan expatriate population, Limassol is unlike any other place in Cyprus. Walk its streets, and you can hear languages like English and Russian just as often as Greek (lately, Limassol has also been known as “Limassolgrad”). In this way, the carnival tradition has persisted as a binding glue between residents of the city—intangible heritage filling in where perhaps the built environment cannot.

Georgiades wrote the book because he worried that the carnival runs the risk of becoming too commercial at the expense of its authentic roots. “The carnival is becoming so huge that a lot of people are making a lot of money,” Georgiades said. “There is a danger the carnival can go in the totally wrong direction.”

Taken together, Georgiades saw Limassol as a city caught in between its lengthy past and its preoccupation for building a new tomorrow. “You have all this construction which concerns the future,” Georgiades said. “You are caught between a mess created for the future and a very heavy past. Where are we now?”

This is the 37th post in The Cyprus Files, a newsletter series from The Usonian chronicling my Fulbright experiences in Cyprus. Thanks for reading, and if you haven’t subscribed to The Usonian to learn about storytelling and design from the edge, please consider joining the list.

I gave a revised version of this talk at a conference in New Zealand. If you want me to give this talk at your venue—or are interested in publishing a version of this story—please DM me!