Rosecrans Baldwin on the city-state of L.A.

"Everything Now" author on L.A. as the city recovers from the fires

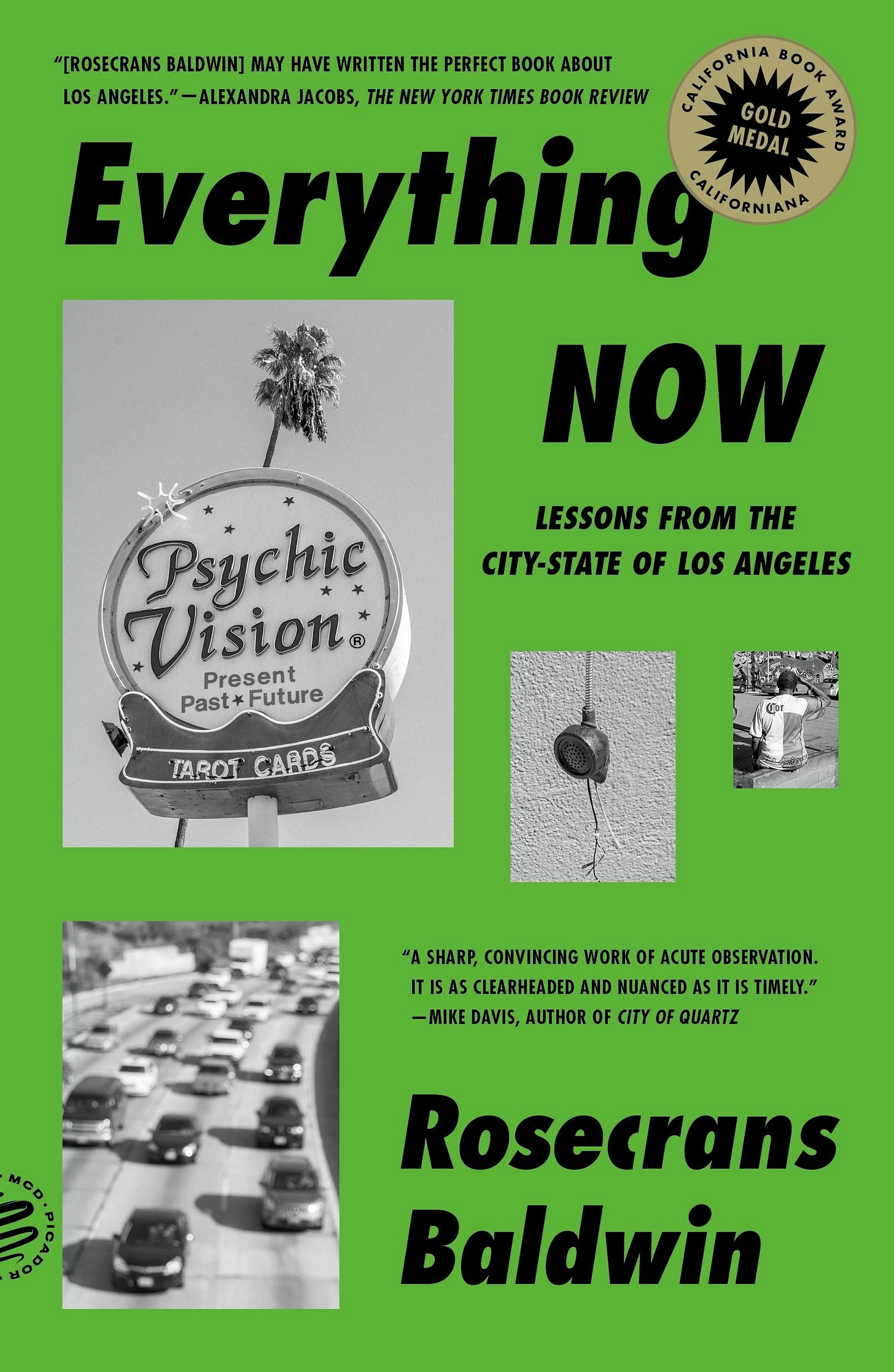

In each installment of “The Usonian Interviews,” The Usonian spotlights a storyteller from a different corner of the globe. This week, The Usonian spoke with author Rosecrans Baldwin about his book Everything Now: Lessons from the City-State of Los Angeles (Picador, 2021), which examines the many facets and contradictions of L.A. with insight and wit.

We discussed L.A.’s devastation due to the Palisades and Eaton fires of January 20251 and L.A. County’s new structure of governance enacted in the 2024 election. Order Everything Now from Bookshop, Barnes & Noble, or Amazon.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length. The views presented by the interview subject are the opinions of the subject and do not represent the views of the article’s author or this newsletter. Browse the full interview archive here.

THE USONIAN: As the Palisades and Eaton Fires raged, I reread your chapter in the book on the 2018 Woolsey Fire (“Everything That Has Happened Here Will Happen Here Again”). In that chapter, your reporting echoes L.A. writer Mike Davis’ arguments in Ecology of Fear, that fire-prone areas like Malibu are inherently dangerous places to live. After this latest round of fire, have your views on this changed?

ROSECRANS BALDWIN: After this round of fire, it's been interesting to watch things that I would expect to see, and then interesting to see things that I didn't see coming. There's been good reporting in Bloomberg and the L.A. Times about vultures from the real estate industry showing up in Altadena and the Palisades to lowball property owners—just to offer cash and get them out of there as soon as possible.

In the reporting for Everything Now, I visited with a family that had gone through the mudslides in Montecito. A disaster of a different type, but still, they had investors. In the book, I talked about a real estate agent who was getting cash offers from foreign investors as the mudslides were still happening.

This is a valuable place. It will continue to be a valuable place, and yet it is also a place, as Davis makes the argument in Ecology of Fear and in City of Quartz, where the concrete that goes into our buildings is sodden with capitalism. This is a place that sometimes doesn't have much care for decency, or human touch, that even to this day it can just seem like a “Wild West” money grab.

But on the flip side of that, the past two weeks, I was really heartened to see all the mutual aid that is filling in for gaps in governance, all the people that are driving strangers to get their groceries, making food, buying ZYN for firefighters. (I say that as someone who is heavily addicted to nicotine, so I sympathize.) That’s been really warming. It’s brought me to tears.

There’s this Davis quote about how or what he told me one time in one of our phone calls: “Whenever you bring large numbers of people from diverse cultures and they have to live with each other, you can’t have a better incubator or crucible for creating new culture. It’s really in my mind the glory of LA.”2 [During the fires] we got to see that, be reminded, heartened, and excited.

These past two weeks have been really tough. I have a cousin who had this adorable little hillside home in Malibu. She had raised her children there. She had survived numerous fires there, and she got burned out this week. I remember eating Thanksgiving on her patio. It’s so pretty. The natural beauty of Los Angeles doesn't quit. The trouble is that when you go up against Mother Nature, Mother Nature bats last—you’re not going to win. You don’t get to triumph. You are foolhardy if you think that this mid-century piece of architecture, beautiful in its own right, is going to withstand fire with large eaves that can catch embers and wooden roofs and with big plane trees built right next to the side of the house—we just can’t build like that anymore.

It’s a harsh reality. The Davis argument “letting Malibu burn,” that is to say places that burn consistently and frequently, places where we devote taxpayer money and put lives at risk in terms of first responders to save and then rebuild—[he argues] we should not rebuild with future fires in mind. Yeah, I get it.

My heart can’t go there right now because of what’s happened to my cousin and what’s happened to all these people, friends of mine who grew up in the Palisades, who grew up and lived in Altadena, talking about having all their memories wiped away. I mean, it’s too soon for me to be able to make the intellectual leap. But it’s not wrong, right?

TU: I wanted to take a step back. In the book, you characterize L.A. and greater Southern California as the “city-state,” this “placeless place” that also has a distinct character. Could you lay out that comparison?

RB: It took me a couple years of living here (I've now lived here for 10 years) to get a sense of what people who grew up here sometimes understand—when you live in “L.A.,” you live in “Greater Los Angeles,” right?

Not just Los Angeles the city, or even Los Angeles the county, but you can live in Huntington Beach and live in “Greater Los Angeles.” You can live in Azusa or Ventura. You can live as far as the edge of Santa Barbara and San Diego, San Bernardino County and Riverside County. You may live in your town, you may live in your neighborhood, and even though you may not leave that place very often, you are a part of a greater whole. And it’s not just the greater whole that is Southern California, which is basically the Mexican border up to the Inland Empire, the Central Valley and its agricultural communities, but across all these communities there is a ghostly presence of “L.A.-ness.”

It's everything from the diversity of the people to the taco trucks, to the Dodgers flags flying off people’s cars. The little ways we have establishing common cultural identity are pretty pervasive here. For people who don’t live here, I mean, I’ve said this numerous times, but Los Angeles is a horrible place to visit as a tourist. There are places to go, right? People come for Disneyland, they’ll come to the city, Venice, Watts or downtown, Hollywood and the Walk of Fame. There are stereotypes and clichés and icons that come out of this place.

But to grasp what it is to be here and an Angeleno is to live here and have a network of friends and to know what it means that if you live on the eastern side of Los Angeles and you have friends in Venice, you’ll see them less frequently than you will see your friends who live on the East Coast of the United States.

Los Angeles County is 88 separate cities. It’s a weird mix, because sometimes those cities feel like neighborhoods less than independent municipalities. And our governance is wild. It’s divided between those city governments, a frequently corrupt City Council, a virtually powerless mayor, and a system of county supervisors that doesn’t make any sense anywhere else.

Interestingly, Angelenos last year elected to have a supervisor to supervise the supervisors,3 which if you listen to certain supervisors’ interviews, it’s been a long time coming, but I think they were reluctant to yield their power. But finally we’ll have someone who will be one of the most powerful political figures in the United States, responsible for millions of people, a vast budget, and huge problems.

The vastness of Los Angeles can be a little bit difficult to understand from the outside. From the inside, it often feels like Instagram, where the scroll never ends. You could be driving from Long Beach to Ventura and be like, “this is Los Angeles,” and it kind of is. It’s not Los Angeles, but it’s “L.A.”

For Everything Now, I interviewed D.J. Waldie, who wrote this great book called Holy Land, a memoir of growing up in Lakewood, which was one of the first “instant cities” of Los Angeles. He very succinctly said that in Lakewood, we know that we don’t live in Los Angeles. We defy the idea of living Los Angeles, but we also know that we definitely live in LA.

That idea of “L.A.” is an identity shared by people who speak different languages, have different religions, have different interests, but similar to a city-state. Long before we had nations, city-states were how people organized themselves. Back when the Earth was more frequently divided into kingdoms, fiefdoms, and empires, basically you would have people gathering around a natural resource, whether a river or access to an ocean. City-states were often places of diversity, and trade was usually the thing that brought them together. City-states defined ancient Greece and Southeast Asia, as well as the areas we now know as Iran, Iraq, and Turkey. Before we had cities and nations, we had city-states.

And to me, landing in Los Angeles 10 years ago, driving around, having no idea what I was experiencing, I was really confused all the time. The more I explored, the more it made sense to me that Los Angeles was different from other big cities in the United States. It didn’t share the bedrock Americana of Boston, Philadelphia, and New York. It had more international reach than Miami or Seattle. It didn’t attach itself to the state of California the way that Houston and Dallas attached itself to the idea of Texas. To me, it really felt like a different kind of place. It’s still a city in the United States. But to apply a little imagination to it, to try to describe the emotional experience of living here, it started to feel like something more.

TU: I attended your talk in Echo Park this past November, and there was a gentleman who made the comment that the borders of L.A., culturally speaking, extended all the way to New York City; he also said, if I recall correctly, “Cleveland was L.A.” I also interviewed some NASA scientists from the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (in La Cañada) this week, and they were telling me they had to shut off contact with the Europa Clipper probe which is on its way to Jupiter—so in a literal sense, what happens in L.A. impacts the entire solar system. How do you consider the city-state’s influence, both ambiguous and literal?

RB: It’s definitely a literal influence on urban planning, from the idea of combining centers of skyscrapers, of which Los Angeles has several, to suburban sprawl, to rural areas, agricultural areas, and true wilderness. This is a biodiversity hot spot in terms of the amount of migrations and species that live here. The natural side of Los Angeles is often overlooked.

New Yorkers love to compare Los Angeles to New York. Los Angeles doesn’t really think about New York at all, outside of people in the entertainment and finance industries. But during this week of fires, I noticed on social media, someone was trying to help confused New Yorkers understand the calamity. They were like, imagine if Central Park's on fire—and I’m like, that’s actually more like 47 Central Parks. Imagine all of Manhattan burning, and throwing in part of Queens.

A friend of mine is a very successful author. He had a book published that just became a massive bestseller. He said, the difference of doing a book signing where 10 people come up and tell you how great your book is, versus 1,000 people getting in line to tell you how great your book is, is mind-blowing and really stressful.

The reason I bring that up is because humans have a hard time with big numbers. When you think about Greater Los Angeles, it’s like 18 and a half million people, and just going by land size, the largest metropolis in the United States. It’s hard to get your mind around in terms of our influence. There’s the urban planning influence, but Los Angeles influences the world through our entertainment industry in Hollywood, but also sporting and music.

Los Angeles is both southern and western-facing. A massive amount of our population got here thinking about Los Angeles as being someplace to the north that resembles places in Mexico, Central America, South America. An enormous amount of our population got here coming east. You know, whether they were coming from Korea, Cambodia, Japan, China, and so on. Those connections to family, to business, and to finance mean that Los Angeles is also really tethered to all those places.

That’s also true of Seattle in the Pacific Rim, and Miami to the Caribbean. Broadly speaking, New York also has a global network, the same way London does, the same way Tokyo and Berlin do, but Los Angeles I consider to be different from New York because Los Angeles is not entrenched.

There are negative aspects to that, like neighborhoods get renamed and redeveloped. In New York City, a CVS becomes a Subway, then a Chipotle, then back to a CVS—but the building doesn’t move too much. And after the 1992 uprising after the Rodney King case, people say there was recovery, but you can still drive around that area. There are huge corners and blocks where commercial development hasn’t returned. We just have a lot of upheaval here—in disasters, in shifting populations.

Because of the hodgepodge of our governance, because of the boom and bust cycles of Los Angeles, there’s a lot of room here to get involved with the city, that you don’t have to be an elected official in city in City Hall to affect change, to have power. Coming back to the fires last week, people are making big differences, and they don’t have to have a lot of power to do it.

TU: I wanted to talk further about the passage of Measure G, which expands the L.A. County Board of Supervisors from 5 to 9 and will feature a “Supervisor of Supervisors.” How could this impact governance here?

RB: To put a person with a name and a face in a position of responsibility—in my opinion, accountability is a good thing. I’m by no means going to carry the banner for the idea of running the government like a corporation. That’s what’s happening in D.C. right now, and we’re going to watch it play out in all kinds of nasty ways. But accountability in governance is a good thing. I believe in democracy. I believe that people should vote.

Los Angeles is a great example of the middle class collapsing. And right now, the traditional idea—which is to say early-20th century to contemporary times—of achieving status and a toe-hold in the middle class with home ownership is collapsing. Right now, with insurance companies leaving Southern California, with prices out of control, with a desperate need for housing—it’s possibly our primary crisis. It’s scary to consider that. In the United States, [the conventional wisdom] was that you have to own a house, that this needs to be your primary way of building investment security; granted, you better hope that someone will buy it from you someday.

But that’s not true in all in other countries, necessarily. If you look at Germany, the percentage of people that rent for their entire lives is much higher, and there’s a lot of protections around that. My attitude is often to be skeptical about the water that I’m told to drink, including the tap water in Los Angeles.

I think it’s a good measure. I’m glad it happened. I don’t have a crystal ball. I don’t know how it will play out, but the idea of someone whose job it is to be held accountable by the voters to getting stuff done seems good to me, because this person will have real power. That’s not true of the mayor of Los Angeles.

TU: L.A. has always been cast in alternate frames—as an utopia, climate-wise, and a noir dystopia more broadly. The book discusses everything from the city’s proclivity to wellness cults to the city’s history of racial discrimination and violence. The book is called “Everything Now.” How do we reconcile all these conflicting aspects happening all at once?

RB: We don’t. There’s a quote from the psychotherapist Esther Perel, about how when you have multiple conflicts happening, whether in one individual psyche or within a couple, it’s not about reconciliation, it’s about managing the contradictions. This is a big place with a lot of people. A lot of people have different interests that can be opposed to one another, that can be in common with each other, but they’re not going to be the same any more than two people’s interests are going to be the same in a relationship.

But harmony is about managing the contradictions. It is about accepting the idea that there will always be difference and finding balance through that acceptance. On the one hand, you have the supposed open-mindedness and tolerance that is in the new age-y side of Los Angeles, its embrace of mystics and crystals and cults, Kundalini Yoga, “healthy” food, and so on.

At the same time, as long as Los Angeles has been here, a deep history of racial intolerance and crime, brutality, and incarceration. When you think about people who came to Los Angeles in the first place—once the railroads were built, you had a lot of Southerners arriving here, and that is white Southerners bringing the Ku Klux Klan with them, which had long strongholds here, in Huntington Beach or white power in El Segundo. And you also had Black families fleeing the south during and after Reconstruction. Then you had people from Iowa seeking health cures. You have Los Angeles boosterism for years, spelling one thing after another to get people to come here. And so people arrive with these attitudes, and ideas and hopes and dreams, and now we have this great diversity thanks to all of them.

Frankly, it’s about management. It’s about expectations. There’s a documentary made about the food critic Jonathan Gold called City of Gold. And he has a line in there about how, when you have all these people from all these backgrounds essentially forced to live on top of one another—it’s in the fissures, the little places where they meet that you find the best things about Los Angeles.

But I do think that that engenders a sense of tolerance. And I don’t mean tolerance in terms of the far end of new age-y-ness, of being open to everything—I don’t mean tolerance in terms of a very disgruntled acceptance of the first Black or Asian person to move into your neighborhood, because Los Angeles has had multiple waves of white flight, Black flight. This neighborhood was Jewish, and then it was Latino, and so on. We’ve had all these different evolutions, but tolerance in terms of a moderate sense of empathy, a moderate sense of acceptance and ideally finding that you will benefit from that person benefiting too.

I do think that's a hallmark of Los Angeles, in a good way. I remember when I was talking to D.J. Waldie. He was making a point, and he really backed away from it. But I actually thought it was more true than he thought. He said we have this extraordinary climate, this beautiful Mediterranean climate of 323 days a year of sunshine, and we’re outside all the time. Yes, we’re in our cars. But that cliché is kind of overblown.

You might never leave your neighborhood, whether it’s Latino, white, Asian, Black—you might just see the same people all the time, but the truth is, a lot of us are on the move, and you can’t help but just keep running into people, especially people that are living unhoused, that are living in tents, on your sidewalk—unless you live in Irvine, that’s probably a daily aspect of your life. And yeah, you can roll up the tinted windows on your Range Rover and pretend it’s not there. But that’s not the common experience. The common experience of Los Angeles is—though you don’t see this on screen—people who ride the bus, and people who work jobs with people who don't have the same background as them. That does lead to a sense of, common interest and common purpose. And that’s where I come back to the city-state idea—by doing for you, I’m doing for me.

People outside Los Angeles love to hate Los Angeles. If that’s their point of view, the thing that I know to be true is L.A. doesn’t give a shit. We really don’t care. We invite you to come to Disneyland. We invite you to come discover this wonderful place full of beauty and diversity and interesting things and gritty architecture and pain and suffering. We’re open to you experiencing it, and at the same time, if you want to talk shit, that’s fine. You’ve been talking shit for hundreds of years. It’s the same voices, and again, we don’t care.

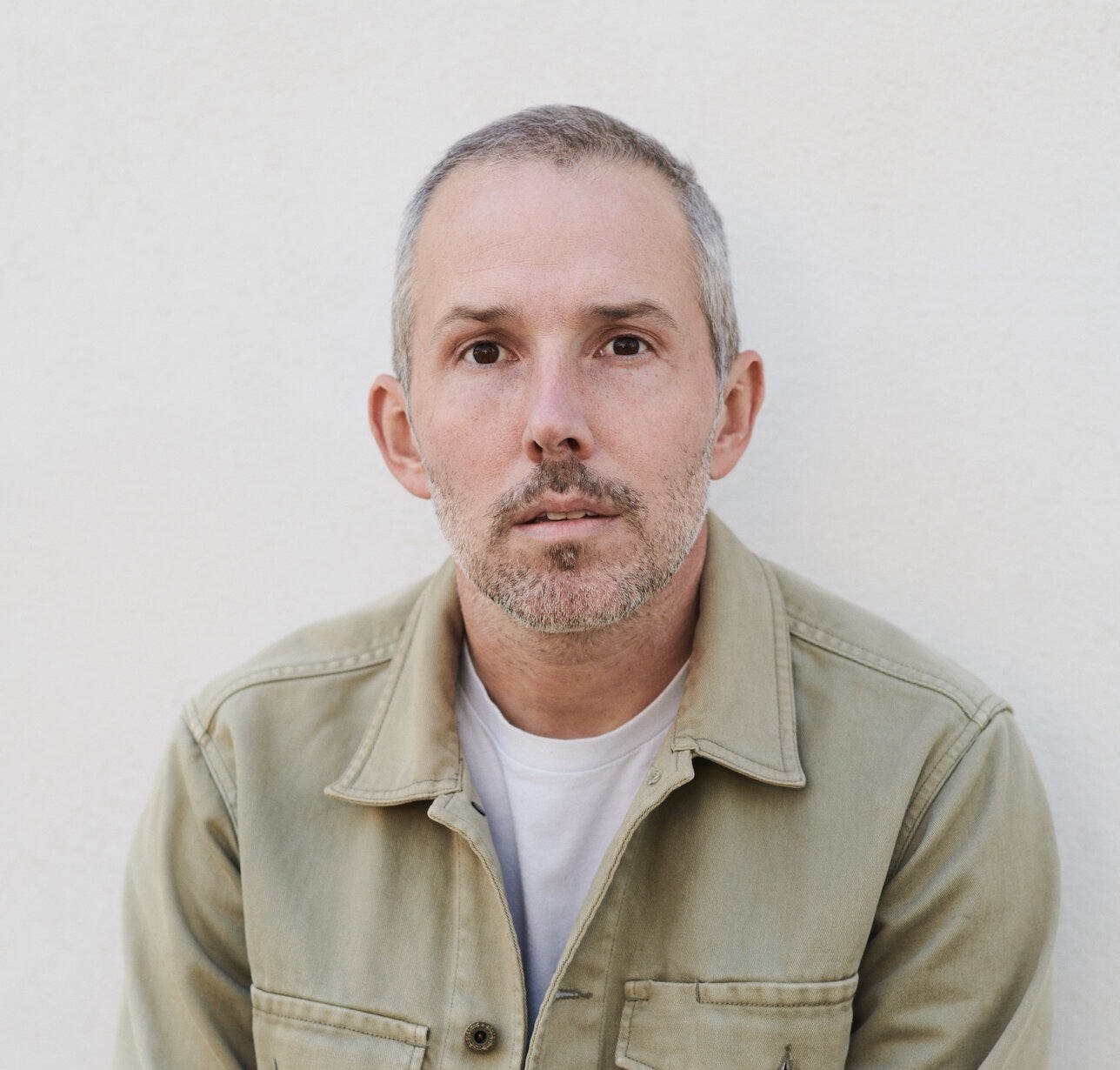

Rosecrans Baldwin is the bestselling author of Everything Now, winner of the California Book Award. Rosecrans is a correspondent for GQ and a frequent contributor at Travel + Leisure. Several of his articles have been selected for the Best American Essays and Best American Travel Writing collections, and he was a finalist for a James Beard Foundation Journalism Award. On Substack, he writes “Meditations in an Emergency,” a weekly essay about something beautiful, with a Sunday supplement for supporters. He lives in Los Angeles.

Read my coverage of the fires for Princeton Alumni Weekly here (which I also ruminated on in last week’s issue of The Usonian).

Measure G, which expanded the L.A. County Board of Supervisors from 5 to 9, passed in the 2024 election.