Famagusta Collage, Part III: City of Othello

Medieval and Renaissance clearinghouse between Europe and the Near East

“I am very glad to see you, signior.

Welcome to Cyprus.”

–Iago, to Othello,

in William Shakespeare’s “Othello” (1603)

About eight hundred years ago, a fabulously wealthy city emerged on the golden shores of the Mediterranean island of Cyprus. The city’s name in Greek was Αμμόχωστος, a name which meant “hidden in the sand.” But this city was ruled by the Franks, and they called it Famagusta, and under the rule of the French-speaking kings the city was anything but inconspicuous.

This is Part III of a five-part series on the history of Famagusta. We’re moving through time quickly, and this time we’ve jumped ahead 2000 years, more or less. [Catch up with Parts I and II here.] But now, we’ve moved on to the medieval city which remains the traditional heart of the city today.

Medieval Dubai?

The last European outpost of the Crusades standing after Saladin’s reconquest of Jerusalem, Famagusta’s port became fabulously wealthy as an European clearinghouse between Europe and the Middle East, bypassing Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul) in the spice trade—that is, until the European discovery of the Americas and the colonization of South Asia and Oceania started eroding Venetian and Ottoman spice monopolies for good.

The staggering wealth of Famagusta meant that massive sandstone cathedrals were built here, the medieval version of conspicuous consumption you might today see in Dubai (or heck, on the other side of the island of Cyprus, in Limassol). Today these cathedrals stand like eroded coral reefs, majestic ships of stone that have seemingly accreted here, some in a state of partial ruin for more than five hundred years. It was here, within the halls of the grandest cathedral of Saint Nicholas, that the French kings of Cyprus were crowned the “kings of Jerusalem”—really, more of an aspiration to identify with an historical blip of proto-colonial sovereignty than anything else. Think of medieval royalty like the modern-day CEO—you could remove a king from one domain just for them to be appointed to run another.

Venice and Othello

When the Venetians took control of Cyprus in the late 1400s, a hostile takeover that involved marrying off a queen, they armed that glamorous port city to the teeth. Fearing the domineering Ottoman presence just miles away, the Venetians upgraded the French-built walls around the city, some of the most impressive of the Renaissance. After all, the Serene Republic, at the height of its empire, was a naval cartel.

And it was in that context, with Venetian Cyprus preparing for war, that Shakespeare chose to set his tragedy of a warrior betrayed by his own comrade. The play’s name was Othello. To refresh your high school reading list: Othello, a Moorish captain of Venice (typically cast as a Black lead) is married to the white Desdemona, daughter of a Venetian senator. Othello’s subordinate, Iago, bitter at Othello passing him over for promotion, convinces Othello that Desdemona has been unfaithful, and in his rage, Othello murders her.

However, when Othello finds out that he was misinformed, he takes his own life. Iago is punished, but he never elaborates as to his exact motive. A melodrama with themes of race and jealousy, Othello has endured as a classic story, and in 2001 it was even staged as taking place on a high school basketball team in Julia Stiles’ very weird but engaging Shakespeare adaptation, O.

Othello may be inspired by an Italian folktale drawn from a real-life incident (if that doesn’t sound like a line from Knives Out, then I don’t know what does). But the title character may also bear some inspiration to an historical Venetian doge named Cristoforo Moro, as well as a London court visit by the ambassador from the Barbary Coast in Shakespeare’s time—but of course the inception of a story is a multitude of factors including the air pressure of the days and weeks Shakespeare composed the play, so all that stuff is fine-grain trivia to debate about.

And though Shakespeare never refers to Famagusta by name, this is the port of Cyprus that would have been the epitome of the Cyprus Shakespeare was describing—a Cyprus that by the 1603 release of Othello was more than a generation gone.

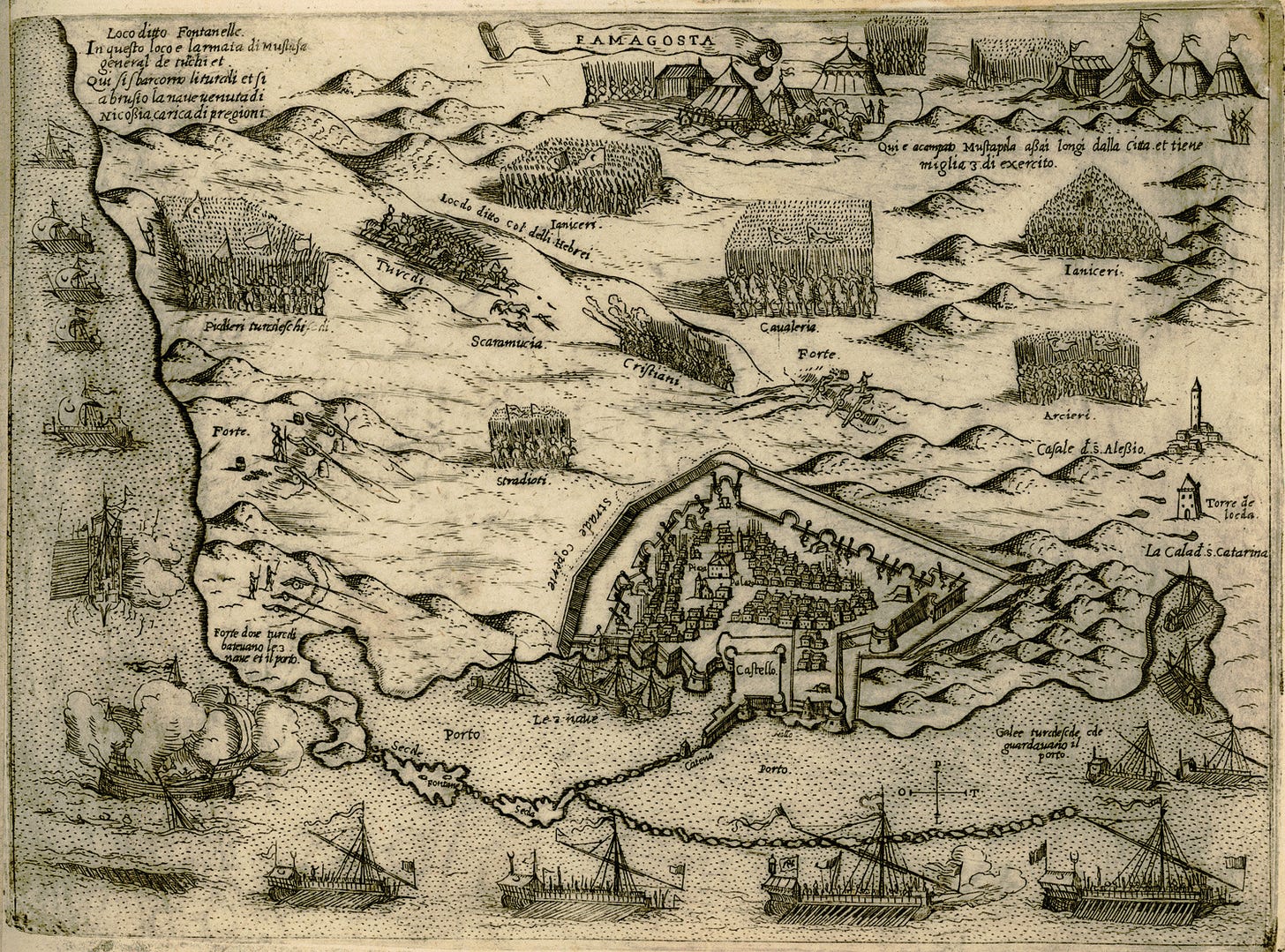

The siege of Famagusta

In 1570, Sultan Selim II sent a fiery letter to the Venetian rulers of Cyprus demanding the handover of the island to the Ottoman Empire. Here is a sample of what the letter contained:

“The providence of the Gods has given me the right to destroy the faith of the Christians and to become the sovereign of all. I greet all of you who have in an unjust and abusive manner inveighed against me. And you give me the right to take revenge and to crush both you and those who support you, who are guilty of the bloodshed which they have caused among my brethren. It will not be difficult with my sharp sword to inflict utter defeat upon you and neither hope nor strength nor your wealth will be able to help you. And so great is the power which I have at sea that before me you will all be swiftly turned to flight…. I will wipe you out, I will put you all to death, I will lay waste everything…”1

To our modern ears, this statement seems pretty scary, but was not so uncommon in those days. The Crusaders under the Knights Templar had taken over the island with much the same brutality a few hundred years before.

But the threat was not without commitment. Once the Ottoman siege began on the island, it was a decisive campaign. The capital of Nicosia fell first, in the matter of a month. Famagusta’s siege, however, lasted nearly an entire year, and the defenders were reduced to starvation. The damage of the bombardment on the city’s many ornate churches is still evident today.

I’ve touched on this story on this newsletter before, but it’s so captivating I had to touch on it again. Such a defense required strong leadership, and the Venetians were led by a particularly savvy Venetian captain named Marcantonio Bragadin. His military genius greatly flustered his mercurial Ottoman opponent, Lala Mustafa Pasha.

Eventually, the Venetians had no choice but to surrender. And the defenders came to favorable terms with Lala Mustafa, an agreement that would allow them safe passage to depart the city. Now, at this point the accounts diverge. Some historians claim that Bragadin executed some Turkish prisoners. Others don’t mention that at all, arguing that Lala Mustafa was after some buried treasure. Either way, Lala Mustafa must have felt embarrassed by the length of the siege, given his greater numbers.

Lala Mustafa had Bragadin and his comrades arrested and tortured. In a horrific episode that surely inspired George R.R. Martin in his composition of the Game of Thrones books, Bragadin was flayed alive and his skin stuffed, an echo of the cruelty of the ancient world, of a similar fate that perhaps befell Emperor Valerian after he was captured by the Persians in 260 CE. Eventually Bragadin’s remains were smuggled out of Constantinople and returned to Venice, where they were interred in the city’s Basilica dei Santi Giovanni e Paolo.

The Ottomans had taken over Cyprus, and with that, one of the final pieces of the island’s modern character was established, becoming once again a true entrepôt between East and West. Some would say the events set the stage, or at least foreshadowed, the island’s current predicament. As always, the truth is more complicated.

The green-eyed monster

As we have seen, throughout its history Famagusta has been the site of such wealth and power, and with that elevated position came cruelty and greed. It is fitting that the Shakespeare play Othello, about envy, was set in Renaissance Famagusta. As Iago states in the play, “beware my lord of jealousy. It is the green-eyed monster which doth mock the meat it feeds on.”

For our next chapter in the Famagusta Collage, we will travel another few hundred years forward, to the waning period of British rule of the island after World War II, during another episode of power, cruelty, desire, and change.

But for a moment, let’s turn back to Othello. Although the play’s themes telegraph a warning about the vicissitudes of human nature, the play itself can also serve as a symbol of hope.

From 2014 to 2015, the Tower of Othello was restored by the Bi-Communal Technical Committee on Cultural Heritage, a group that pursues conservation projects for endangered monuments across the island. In 2015, a performance of Othello was held inside the restored castle itself, with a cast of Greek-Cypriot and Turkish-Cypriot actors.2 Attended by the then-respective leaders of the Greek Cypriot and Turkish Cypriot communities, Nicos Anasastiades and Mustafa Akıncı, the event was a gesture of hope in a long contested city, a place where harmony had given the community its gleaming vitality in the past, a quality it one day may achieve again in a reunited Cyprus.

This is the thirty-fourth post in The Cyprus Files, a newsletter series from The Usonian chronicling my Fulbright experiences in Cyprus. Thanks for reading, and if you haven’t subscribed to The Usonian to learn about storytelling and design from the edge, please consider joining the list.

From Koumarianou, Catherine. Avvisi [1570-1572] The War of Cyprus. op. cit., p. 62. qtd in Marangou and Coutas, Nicosia: The History of the City. Cassoulides: Nicosia, 2022, p. 121.

“The Technical Committee on Cultural Heritage in Cyprus,” Technical Committee on Cultural Heritage, 2018, pp. 34-35.