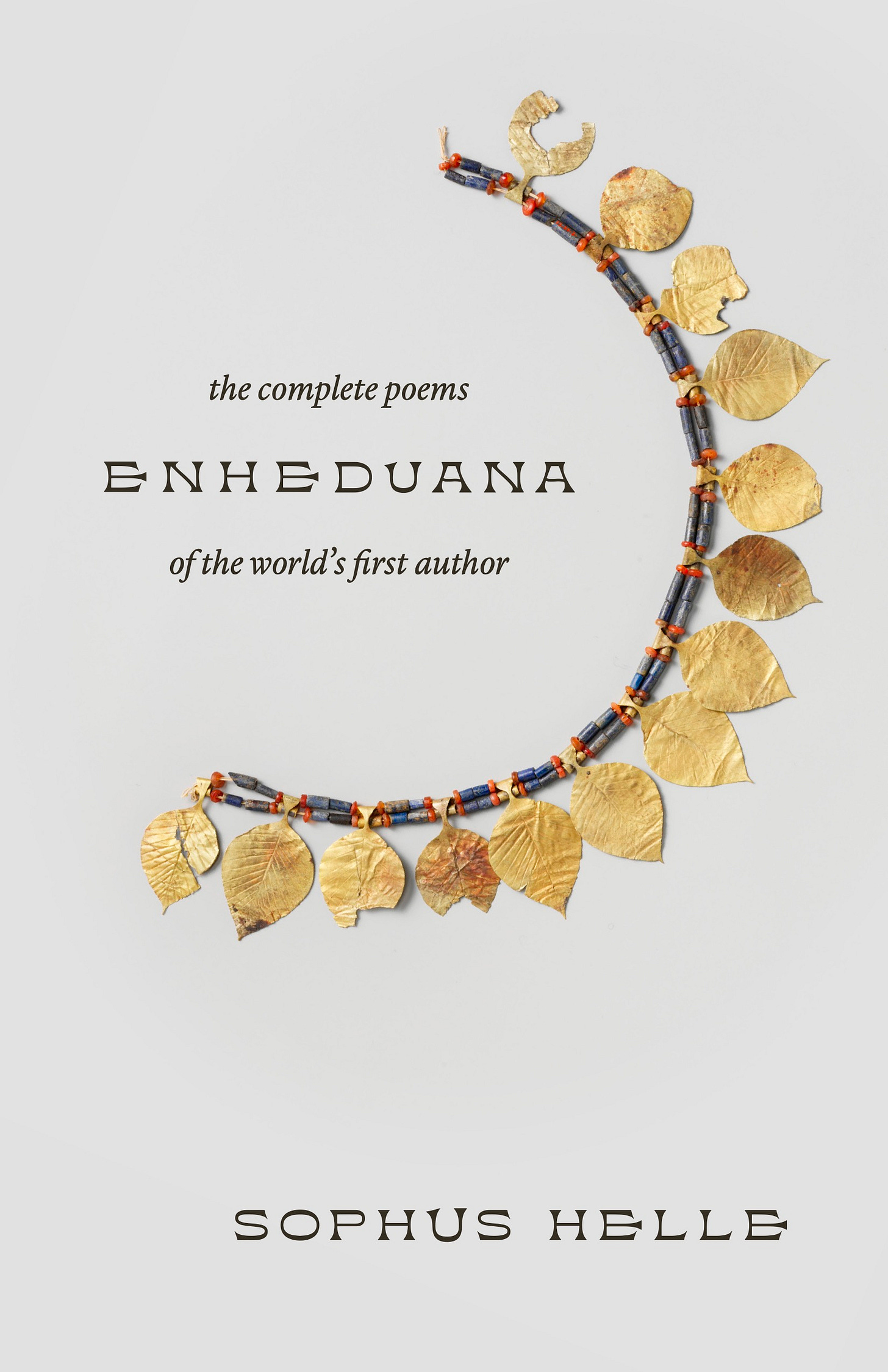

In each installment of “The Usonian Interviews,” The Usonian spotlights a storyteller from a different corner of the globe. This week, The Usonian spoke with translator Sophus Helle about his groundbreaking translation of the poems of Enheduana, considered to be the world’s first author. An Akkadian priestess (and princess) from the 23rd century B.C.E, Enheduana’s father Sargon founded the world’s first empire in Mesopotamia—and Enheduana was the first person in history to be attributed as an author.

You can order the book from Yale UP, Bookshop, or Amazon.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length. The views presented by the interview subject are the opinions of the subject and do not represent the views of the article’s author or this newsletter. Browse the full interview archive here.

THE USONIAN: Both your translation of Gilgamesh and the poems of Enheduana bring the world of the Akkadian, and later Babylonian, Empires to life. What brought you to the ancient world of the Akkadian and Babylonian empires? What keeps your head there?

SOPHUS HELLE: I originally wanted to go back in time as far as possible and explore the oldest known cultures of humanity, because I had a foolish teenage dream that doing that would reveal some sort of truth about humanity. I don’t really believe that anymore, but on my search for a distant past, I came across these cultures, and they appealed to me very powerfully.

One of the reasons that they appeal to me is simply that there is so much amazing material. Of course, I specialize in the literary material, but there’s wonderful material of all sorts, and that material has been explored very little. There’s been a century of work, but so much of that work has been building the foundation of the discipline, rather than reaping the full benefits of what these works can teach and show us.

I entered the field at a very propitious moment where a lot of this groundwork had finally been laid. The major text editions and dictionaries and such were finished just before I entered the field, and so now we’re entering a new phase, where there’s a lot more potential for new kinds of analysis. To give you another example, last year saw the launch of the Electronic Babylonian Library, which is an amazing resource for doing this kind of work. The field is on the cusp of something new and very exciting, and I’m very happy to be part of that.

TU: For our readers, who was Enheduana, and what do we know about her?

SH: A colleague of mine has come up with this great phrase to understand in Enheduana’s history, which is that “she lived three lives.”

The first, as a historical person in what’s called the “Old Akkadian” period, the 23rd century B.C.E.

The second, as a literary author and sort of “literary star” 500 years later, in what was called the “Old Babylonian” period (18th century B.C.E.), which is when the manuscripts of her poems are from.

Her third life is her current one as the speaker who is coming back to life today.

We know relatively little about the historical person, but we do know that she existed. She was the daughter of King Sargon who created the first known empire and installed Enheduana as High Priestess of the Moon god Nanna in the city of Ur. We don’t know where she died or when she would have been born (and that kind of stuff), but we have the names of her servants from these cylinder seals that you would have used as a form of personal identification. And we found the graves and the seals of some of Enheduana’s servants, which gives us these fascinating flashes [into her life].

But our understanding of her as a figure in literary history comes from these poems that were attributed to her. The manuscripts of her poems that have been recovered were written down 500 years after her death. It is unclear whether they were written later in her name, but it wouldn’t be all that unusual in Sumerian poetry for this sort of gap to exist, even if she did write the poems herself, because the Old Babylonian period, and specifically the 1740s B.C.E., is a time of huge textual finds. We have a lot of text from that specific period. So perhaps [Enheduana is] the first author, or perhaps [she’s] the first subject of “historical fiction.”

Either way, it’s a watershed moment in literary history. Even if the poems were written by somebody else and attributed to her, they still mark the first moment of the very idea of authorship—the very idea of attributing poetry to a human, named individual, rather than to the gods or a collective, anonymous tradition.

It’s with her that that idea is born. And what’s particularly remarkable is that one of the poems attributed to her, the “Exaltation of Inana,” actually picks the moment of authorship. So that’s where she fits into this historical scheme.

But, for instance, let’s say that the poems were composed as late as they could be—the 1750s B.C.E. or something. This was a full thousand years before Homer. So we’re dealing with a huge temporal distance.

The distance between us [in the twenty-first century] and somebody like [Julius Caesar] [in the 1st century B.C.E.] is less than the distance between Caesar and the historical past of Enheduana. It’s a huge temporal remove.

TU: Enheduana was the first known author, and she was a woman. How does that change our perception of the history of literature, and the history of the world?

SH: That’s an excellent question, and a question I can’t answer at the moment. This is literally a question with which the book ends, and I think that’s sort of what I am excited to see answered now. Enheduana is now the first text that students will read in Columbia University’s flagship core curriculum, where they take students through all of Western literary history in one year, beginning with Enheduana.

So it’s slowly making her way into the canon as one of the first texts students encounter. And I think new eyes will see new things in her poems and the continuity between her poems and what came later. On the one hand, she’s like this incredibly interesting figure, not least because of the content of the texts, which are hymns to the goddess of change and contradiction.

But at the same time, she’s also a problematic figure. She is a representative of her father’s empire. In these poems, she asks the goddess who was the patron deity of her father’s empire to rain death down on the rebels. So we can understand her as a proto-feminist, but also a hardened imperialist. And I think these ambiguities are all the more reason for her being in the canon.

The very fact that that her poems just entered public consciousness makes it so exciting. Our understanding of Enheduana will be radically different in 10 years because we’re just opening up to a new kind of inquiry. So these are new questions, fresh questions, and exciting questions.

TU: So who was the goddess Inana? To what importance was she held in the Akkadian culture?

SH: Inana is the main subject in Enheduana’s poetry, and Enheduana does rather striking things with Inana. But overall Inana is the most important goddess in Sumerian, Babylonian, and arguably Assyrian culture. She’s also one of the most interesting goddesses of the ancient world at large.1

It’s often said that she’s the goddess of sex and war, but more generally, she is the goddess of contradictions; in Enheduana’s work, she’s the goddess of change.

Inana’s best known myth is The Descent of Inana, which is the myth that makes its way into Greek culture through the myths of the Persephone, Orpheus, and Adonis, which were all echoes of The Descent of Inana. It’s this great story of how Inana commits a “cosmic suicide” and is then reborn. A strange and wild text.

In general, Inana is associated with reversals and with tricks; for example, there’s how she figures in the epic of Gilgamesh. At the very heart of the story, she carries out what literally critics would call a peripeteia.2 She turns the story around, and the story revolves around those words, because she is the goddess of change. A fascinating figure in all sorts of ways.

TU: In your introduction to Enheduana you outline how these Akkadian texts were preserved by succeeding cultures by scribes who were being trained to write in the Sumerian language, sort of how Latin and ancient Greek remained prestigious languages for well-educated Westerners up to the present day. Can you explain that process for the readers of the blog?

SH: In the case of both Enheduana and Gilgamesh, the main source of manuscripts were the schools. Some centuries after her death, around the year 2000 B.C.E., the Sumerian language died out. It became a language used for scholarship and religious rituals—a lot like Latin and Sanskrit. Considering that comparison, Enheduana was like Virgil in the European Middle Ages. She’s held up as this exemplar of Sumerian [literature]. By studying Enheduana, in a sense you can grasp Sumerian eloquence. The editor of Enheduana’s “Exaltation of Inana” referred to it as the world’s “first bestseller,” which is somewhat anachronistic, but it gives you a sense of a special place [the text had] in the school.

Gilgamesh is also known from the imperial archive in the city of Nineveh. The Royal Library of Nineveh had great manuscripts—they weren’t written by students, but by the king’s scholars.

TU: In your introduction, you say philologists have been reluctant to seriously consider Enheduana’s poetry due to the question of authorship—are these poems about the priestess Enheduana, or were they written about here. Does that question matter, and if not, what are the questions we should be asking?

SH: This question has really dominated the study of Enheduana recently. And I think there was a sense that nothing else could be done with the poems, apart from the philological editions of them and the debate about when they could be placed in time. There are all sorts of other questions to be asked about them, about their literary structure, the world they summon, how they discuss the goddess Inana, and how they think about authorship.

Let’s assume, for a moment, that the poems were written by Enheduana herself. Then, the “Exaltation of Inana” is about how Inana should replace her aging father as ruler among the gods, which is very interesting in a biographical sense.

This is a poem in which Enheduana does not mention her father directly, which is an interesting choice in itself. I wonder who she thought would have been worth succeeding to the throne. But that sort of reading is only possible if we assume that it is the actual historical person who wrote these texts.

[Therefore] I don’t think that the question is irrelevant—it is one among several you can ask. And I think the qualities and the complexities of the poems are worth attending to, whether these are by or about Enheduana. I don’t think that these questions should prevent us from proselytizing or promoting these texts, but the question still fascinates me. Both options are very interesting.

TU: What are (some of) the challenges of translating Sumerian to English? You had previously translated it into Danish—did you go from Danish into English or back to the source?

SH: I’m more likely to go into straight into English. The main challenge—and this goes for translating both Sumerian and Akkadian—is that they’re really good at condensation. They can capture a lot of meaning in very short lines, especially when the language is being used in literary ways. But I often find that three Sumerian words come to fifty English words. Enheduana really pushes this condensation as far as it will go. That means it’s quite difficult to capture the intensity of the original text in an English translation.

TU: In both your translation of Gilgamesh and Enheduana, you denote where we are missing lines in the poem, which creates this curious space that allows the reader to imagine what might go there. How do we know that there are lines missing? What effect do you hope this stylistic decision has on a reader’s experience with the work?

SH: First of all, when you’re looking at a page of [cuneiform] text, let’s say that that page has no ellipses. That doesn’t mean it’s one complete manuscript. There’s actually a patchwork of seven or eight times scripts behind it. The ellipses indicate when all the manuscripts are broken in that particular section. This is a constant feature of Sumerian and Akkadian poetry. The “Exaltation of Inana” is one of the only major literary cuneiform compositions that is not fragmentary. That’s the exception.

Whereas, in Gilgamesh, as much as two-fifths of the poem are missing. Some of what appears as words in the translation that it’s based on; these reconstructions can be more or less speculative. Some of it is not speculative at all, because we can tell that the text is repeating itself just because we have any bit of the line. We can copy-paste from other sections of the poem where other parts are more speculative in nature as reconstructions.

It was important to signal the missing text when no reconstruction was available. The missing text actually has a lot of power. There was a playwright who said Gilgamesh would not be as powerful if it were not for the thousand ellipses.

One of my favorite pages in Gilgamesh is the one in which Enkidu dies, and there’s an entirely blank page. He’s alive on the page before it, and dead on the page after it. So this must be where he dies. But we have about thirty lines missing there.

As for how we estimate the length of a break? There are various philological methods to do so. That's quite a complex operation, but we’re often held along by the fact that a lot of these tablets note at the end how many lines they they contain. That can give us an estimate. But sometimes it’s things like looking at the curvature of the tablet to estimate how much is missing, which is a lot more difficult.

TU: In one of the book’s essays, you call your vocation one of finding “overlooked stories and [bringing] them to life,” i.e., “historical dumpster-diving.” Gilgamesh isn’t exactly the “dumpster.” But even so, what’s next on the list, if I may ask?

SH: I will still say that, any other epic in World Literature, it’s much less studied than The Iliad, The Odyssey, or Beowulf. There are so many things to do and say about Gilgamesh.

It’s that sense of novelty that I really enjoy, and that's just Gilgamesh. Then there are all the other Babylonian epics that are even less studied. You know, I have a book coming out about Atra-Hasis, which is another amazing epic from Babylonian culture that has so much to say with this moment in particular, in part because it is about catastrophic climate change, and the relation between climate change and oppressive work conditions.

And then there’s the Epic of Erra which is about how do you prevent war. And two weeks ago, published with some colleagues a new translation and edited volume about Enuma Elish (the Babylonian epic of creation). The Enuma Elish book is the first volume in model in what we’re calling the Library of Babylonian Literature. That will take up a lot of my time as we go through the major classics of Babylonian poetry and dedicate these volumes to them.

The next that is coming out is the volume on Ludlul, which is the Babylonian precursor to the story of Job. Ludlul is, if you can believe it, even more depressing than Job.” These are some of the texts that I’m working on, but I’m hoping to spend time with as many of these cuneiform poems as I can, and try to present them to new audiences.

TU: What do you hope readers get out of your work?

SH: I take it to be my task to present cuneiform literature to the modern world, but what each text has to say is very different, and different readers will take different things even from the same text.

One of the things I love about Gilgamesh, which is that everybody seems to see something different in it. Some people respond to some themes about love between men. Others respond to the theme of loss. Others responds to the search for immortality, and still others to the contrast between nature and culture. And that's just one text.

I wouldn’t want to say what people should take from Gilgamesh or Enheduana, because I’m interested in people taking different things from it. That is also true of Babylonian literature more generally. But I also want to emphasize that these are texts that come from cuneiform culture that existed over a period of three thousand years. These texts come from a huge variety of periods and context, and they tell different stories with different messages. There isn’t one Babylonian or Sumerian way of looking at the world. But I think my job is more to make the case for these texts as strongly as I can, and then let people see what they take away from them.

Sophus Helle holds a PhD in Comparative Literature from Aarhus University, 2020; MA in Assyriology from the University of Copenhagen, 2017; winner of the European Young Researcher Award 2020 Popular Prize and the Aarhus University Research Foundation 2021 PhD Prize. Since September 2023, he has been a postdoctoral fellow at Princeton University with a stipend from DFF. He is a regular contributor to the Danish newspaper Weekendavisen and a board member of the Danish Institute in Athens.

Inana is the name of the goddess in Sumerian, but she may be better known by her name in Akkadian—Ishtar.

Literally, from Greek, a reversal.