A fishy story

Narrative Architecture #6: The many strange narrative choices of Herman Melville's "Moby-Dick"

This is the sixth chapter in a long-simmering miniseries called “Narrative Architecture” about storytelling choices in fiction. There are many ways to tell a story, and in this series, I’ll examine the literary choices a particular author made and their impact on the story at hand. This week, I’ll engage with the greatest fish-tale of them all—Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick, beloved by many, and yet resented by so many more middle schoolers forced to, um, “plumb the depths” for the elusive white whale. (Sorry, I couldn’t resist!)

This post is a revised version of an essay I composed as part of my MFA program at UNR.

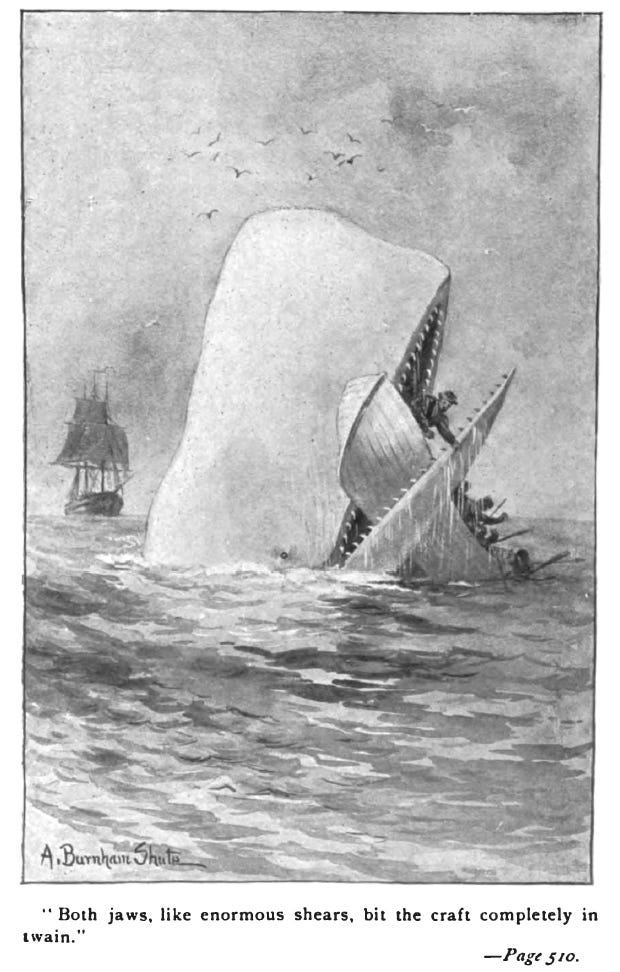

Let’s get this out of the way—Herman Melville’s 1851 novel Moby-Dick follows an intellectual known as “Ishmael” as he joins the voyage of the Pequod, where he bears witness Captain Ahab’s mad quest to kill the eponymous white whale.

While that sounds like fine groundwork for a seafaring adventure novel, Melville’s narrative structure significantly deviates from what might have been a more conventional fish story. In this post, I’ll consider the novel’s overzealous front matter, the various narrative styles depicted, and the book’s self-conscious haphazard organization of material. By considering the classic doorstop through these lenses, we can see that Moby-Dick is both an example of what to do and what not to do in terms of writing an adventure novel.

Epigraphs: The quotes at the beginning

If we start from the beginning—the very beginning—let’s talk about Moby-Dick’s absolutely insane epigraph. Usually, epigraphs are included in the front matter to signal the book’s themes. To name a prominent adventure example, Michael Crichton’s Jurassic Park opens with two lines from Linnaeus and Chargaff. In particular, the Linnaeus quote sums up the theme of the novel:

Reptiles are abhorrent because of their cold body, pale color, cartilaginous skeleton, filthy skin, squalid habitation, and terrible venom; wherefore their Creator has not exerted his powers to make many of them (viii).

In such a short space, Crichton’s quote is pulling double-duty by addressing how dinosaurs are “terrible lizards” and hitting on the book’s theme as a cautionary creation story.

As for Melville’s book, it opens with two sections of front matter, and while they strive to give the reader a sense of what to expect, they are much less efficient in meeting that objective. The first section of front matter is a note on “Etymology,” which provides several dictionary definitions of whales, and then translations of the term in Hebrew, Greek, Latin, Dutch, “Feegee” (Fiji), etc. (xxxiv-xxxviii). To a modern reader, this seems innocuous enough, given that this section is only a page-and-a-half.

But then there are the “Extracts”—a collection of about 80 quotes related to whales from a variety of sources, including the Bible, Pliny, Jefferson, and more obscure, possibly fictional sources, such as what is referred to as “‘Something’ unpublished” (xl-li). These extracts tend toward a portentous tone, characterizing whales as a malevolent force observed throughout the ages, such as in Lord Bacon’s Version of the Psalms: “The great Leviathan that maketh the seas to seethe like boiling pan” (xli).

But the front matter’s is attributed to a “Late Consumptive Usher to a Grammar School” and a “Sub-Sub-Librarian”—contradicting the ominous sentiment (xxiv, xl). Rather, these offbeat descriptions of authorship veer on parody.

Was Melville attempting to suggest his book was not just a whaling adventure, but a self-aware fish story? Even if that was his intention, he certainly could have accomplished the same goal more efficiently, with two quotes instead of eighty. But without the advantage of Google, perhaps he thought he was doing his readers a favor with all the pre-text trivia.

Narrative styles: An exercise in “variety”

Melville’s narrator Ishmael seems to take on several different prose styles, of which I discuss two here: his Emersonian efforts in “The Whiteness of the Whale” and his satirical amateur natural scientist persona which appears throughout the book. In Emersonian fashion, Ishmael conflates the problem of the whale’s whiteness with that of the soul:

But not have we solved the incantation of this whiteness, and learned why it appeals with such power to the soul… and yet it should be as it is, the intensifying agent in things the most appalling to mankind (211-212).

The melodrama of Ishmael’s whiteness contemplation takes up eight pages, which is quite a long time to riff on an extended metaphor (204-212). Melville spends far more time in the voice of an amateur natural scientist. In at least three extensive chapters, the narrator introduces the reader to his interpretation of the taxonomy of whales in “Cetology,” “Monstrous Pictures of Whales,” “Less Erroneous Pictures of Whales” (145-157, 285-289, 290-293). We know that Melville is indeed familiar with Cuvier, Linnaeus and Agassiz since he directly references their style of tedious, gentlemanly scholarship in the text (146-148, 334). He even proposes to be an earth scientist, though clearly satirically:

Ere entering upon the subject of Fossil Whales, I present my credentials as a geologist, by stating that in my miscellaneous time I have been a stone-mason, and also a great digger of ditches, canals and wells, wine-vaults, cellars, and cisterns of all sorts (497).

Since the geology of the era resembled more of a gentleman’s hobby than a modern discipline, Melville seems to be poking fun of wealthy aristocrats interested in geology, their only expertise in that they had held a shovel before. In keeping with the amateur confidence of contemporary natural scientists, at one point Ishmael dares to propose his own hypothesis on whale spouts: “the spout is nothing but mist,” a conclusion he reaches not from scientific certitude but “by considerations touching the great dignity and sublimity of the Sperm Whale” (409). Shallow evidence, ego, and inconsistent logic appear to be Melville’s targets with his cetological prose—unless he really just wanted to express his views on whale anatomy.

(Lack of) organization

Melville’s organizational approach is more haphazard. His narrator often flags background whale trivia as necessary to understanding upcoming whale-chase action sequences:

With reference to the whaling scene shortly to be described, as well as for the better understanding of all similar scenes elsewhere presented, I have here to speak of the magical, sometimes horrible whale line (60).

Often, the information is presented ahead of these action sequences, but on several occasions the background introduced retroactively explains necessary elements. “Chapter 62: The Dart” explains an aspect of harpooning relevant to the chapter that preceded it, and “Chapter 70: The Sphynx” opens with the admission:

…it should not have been omitted that previous to completely stripping the body of the leviathan, he was beheaded (313, 338).

The explanatory chapters thus alternate between prospective set-up, and retroactive apologetic explanations. Through the guise of Ishmael, Melville even seems to defend (or lament) the fractal nature of his storytelling in “Chapter 63: The Crotch”1:

Out of the trunk, the branches grow; out of them, the twigs. So, in productive subjects, grow the chapters ( 315).

This line does not excuse the retroactive approach—there can be no foreshadowing if all the ominous details are given after the fact, limiting the suspense of Melville’s efforts. I disagree with the tactic, and would not use it for my own writing, unless we indulge in the possibility that Melville intended for his narrator to be interpreted as insane. Especially in later chapters, Ishmael makes several references to insanity:

So man’s insanity is heaven’s sense; and wandering from all mortal reason, man comes at last to that celestial thought… (454)

Not long after, Ishmael describes the mad fervor he possesses when squeezing coagulated whale oil: “I squeezed that sperm till a strange sort of insanity came over me” (456). He later admits to tattooing a skeleton of a sperm whale to his neck, while considering nothing odd of it (491-492).

These details made me wonder whether Melville intended Ishmael to have the same arc as the narrator of Nabokov’s Pale Fire—revealed to be ever more delusional over the course of the novel.

All told, Melville’s text suggests there can be a place for incorporating different voices and various types of background information—especially when it supports the goals of suspense and theme—but there are many places where it should not be—as when it stops the novel in its tracks. His book might have been a more successful adventure yarn if the explanations were leaner, set up action, or were omitted entirely.

But, despite all that, I still really like Moby-Dick. Its messiness makes the text richer. Like how Herodotus’ more boring historical sections actually provide key ethnographic information about ancient Egypt to modern historians, Moby-Dick’s excessive detail transports us to a world where whale oil was the critical natural resource, the extraction of which moved the world—but at what cost? Certainly, that allegory is relevant to our present environmental, energy, and climate challenges.

Works Cited

Crichton, Michael. Jurassic Park. Random House, New York, 1990.

Melville, Herman and Delbanco, Andrew (Introduction). Moby-Dick: Or, The Whale. Penguin Classics, New York. 1992.

Nabokov, Vladimir. Pale Fire. Vintage, New York, 1989.

Yes, there is a chapter in Moby-Dick titled “The Crotch.”