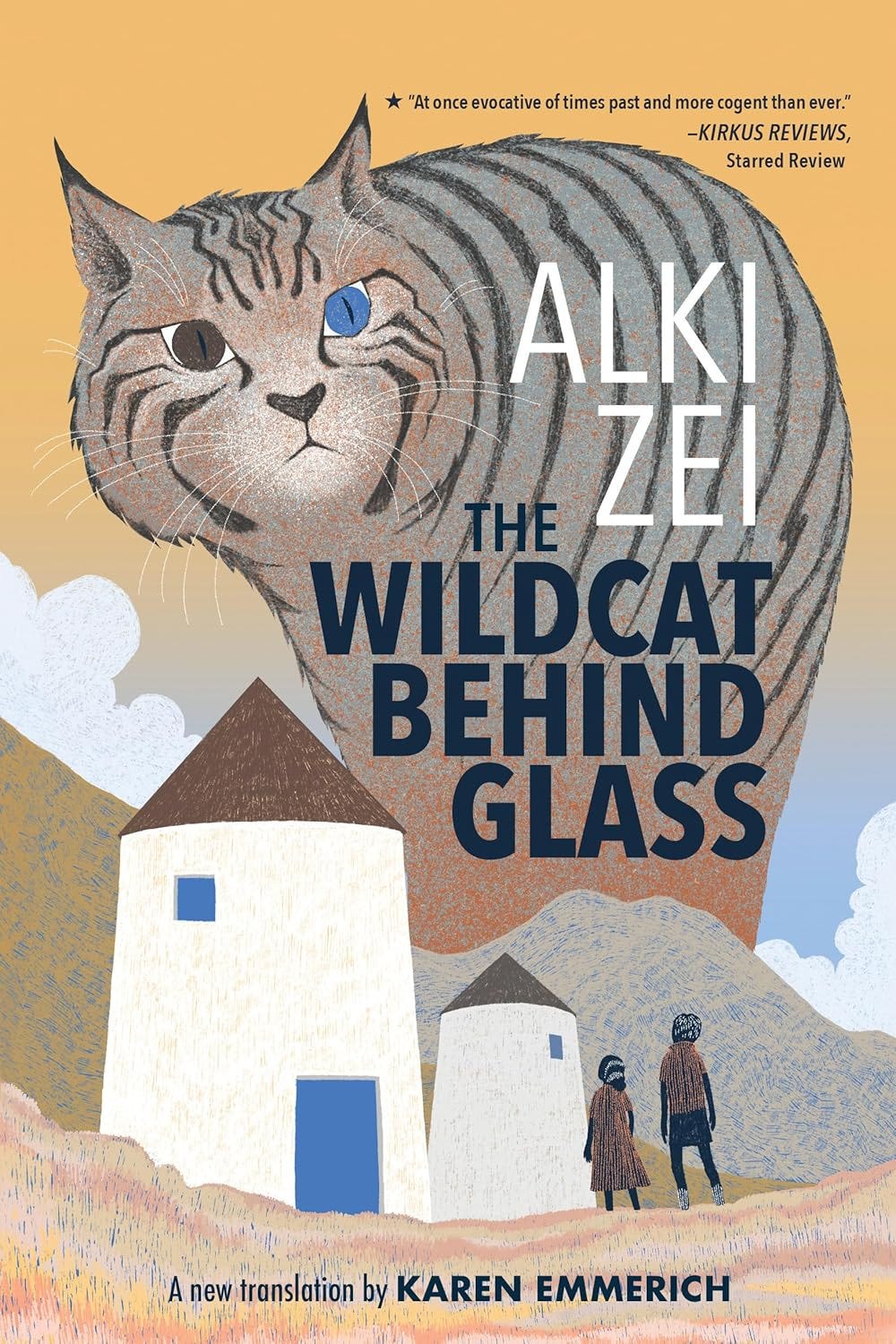

In each installment of “The Usonian Interviews,” The Usonian spotlights a storyteller from a different corner of the globe. This week, The Usonian spoke with literary translator Karen Emmerich about her new translation of Alki Zei’s classic novel The Wildcat Behind Glass (Restless Books, 2024), which first appeared in 1963.

Situated in the period of Greece under the Ioannis Metaxas dictatorship (1936–1941), the novel follows the experience of a little girl named Melia on the Greek island of Samos. Both Melia and her sister Myrto are captivated by a taxidermied wildcat, which their cousin Nikos claims has a life of its own. But as Myrto is drawn into the politics of fascism, Melia will confront the evil emerging in her society and family. The novel’s author, Alki Zei, was a political refugee of the Greek Civil War and lived in the USSR for many years. Emmerich’s translation was a USBBY 2025 Outstanding International Book and a Finalist, 2025 GLLI Translated Young Adult Book Prize and reviewed in the New York Times by Adam Gopnik.

You can order the book from Bookshop, Amazon, and directly from the publisher.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length. The views presented by the interview subject are the opinions of the subject and do not represent the views of the article’s author or this newsletter. Browse the full interview archive here.

THE USONIAN: When did you first come across The Wildcat Behind Glass?

KAREN EMMERICH: I first encountered the book in doing research for my translation of Amanda Michalopoulou’s Why I Killed My Best Friend, which came out in 2015. In that book, the characters Anna and Maria reference The Wildcat Behind Glass. One of them gets sick and has to stay home from school. After this girl reads the novel, both girls use the language that Myrto and Melia created for themselves in Wildcat.

The book was also the favorite childhood book of all my leftist Greek friends. I had reached out to the rights holders in 2016, and I was rebuffed, as there already was an English translation. When the book was given to my daughter in 2018, I re-read it almost immediately. Reading it again, I felt this urgency for people to think about fascism and democracy in our moment. It became a little bit of an obsession. Eventually I wore the rights holders down, and they let me take a shot at it.

TU: This is not the first English translation of the novel. What drew you to pursuing your own translation?

KE: The earlier translation of the novel was only available on Amazon print-on-demand. What I wanted to do was create a new translation that would ideally make a splash so that a whole bunch of new people would know about it.

The earlier version was a great translation; it even won a prize, but it came out in the 1960s, and I felt like there were many things that I would have done differently for readers in the twenty-first century, so I thought the book would be best served by a new version.

TU: Alki Zei, the book’s author, was a political dissident, and joined EPON (the youth wing of EAM), the Communist-affiliated resistance in Greece, during World War II. Later she had to flee the country during the Greek Civil War and again during the 1967–1974 junta. The book is somewhat autobiographical to Zei’s upbringing on Samos. What do we know about Zei’s life and how it compared to the events depicted in the novel?

KE: I can’t give you better information than whatever is available online. Zei did write a memoir, With a Faber Pencil No. 2 (in Greek), but it doesn’t include events that would have appeared in Wildcat. She does, however, talk about being sent to live with her grandparents on Samos, being an issue of safety for her and her sister; she did have a sister. I don’t know to what extent anything else tracks with the novel. Did she have a cousin who was involved with the Resistance? Did her sister join the group in Greece that resembled Germany’s “Hitler Youth”?

I don’t know if that stuff is true, but through her godmother Dido Sotiriou, she was from a lefty, artistic family. But it didn’t feel important to know that information for the translation.

TU: There’s something universal about the World War II children’s novel. I felt myself thinking of other classics from this time period, like Eshter Hautzig’s The Endless Steppe or even modern books like Marcus Zusak’s The Book Thief, especially in the element of hiding a friend from authorities and Myrto’s seduction into the fascism of Metaxas’ Greece. Where does this book operate in your mind, especially in the context of how it was received in Greece?

KE: I didn’t read a bunch of other Young Adult literature about the rise of fascism. I did go through a phase of reading YA literature, in part to translate the book so that the register would be more in line with the tone of other books for this age group; I’m thinking of books like The Hate U Give. I also read a lot of YA books that were about family separation, and I was just trying to find get myself immersed in YA books with strong political content. At first, this was to convince myself that there was a home for this novel in the current moment.

But of course, as someone who exists in the world and has also read books for adults about World War II, I knew that the book is already offering itself up as a way of helping younger readers understand something that adults have all kinds of literature to think about.

I was thinking about it in the tradition of Greek leftist political writing, too. The book came out in 1963 and in her memoir, Zei does say that she didn’t even know that it had been published. At that time, she was living in Tashkent (in modern-day Uzbekistan); she had sent this book for publication and it appeared, but she didn’t have access to information about that.

So I was thinking about the book both in terms of an Anglophone–US present, and then also as a book written in the tradition of many different histories of resistance in Greece. That aspect was important to me, both as a reader and a translator. I’ve done some other work that was also about leftist political action and exile (like co-translating Yannis Ritsos’ Diaries of Exile with Edmund Keeley), so that was definitely the surrounding emotional valence for this translation project.

TU: You’ve translated many works of Greek literature for adult audiences. What was different about translating a children’s book? Do you have to make different choices in making the text more accessible to younger audiences? What cultural and historical aspects do you have to contextualize?

KE: I didn’t do a ton of explaining, and this was in part because I had a young reader in my house—my daughter. A lot of the things that people say about translation— readers aren’t going to know this, they’re not going to know that, and you need to explain the cultural context.

That’s the thing—kids don't know anything. They learn the world through reading. My daughter reads books and she can’t pronounce many words in them. She’s reading Harry Potter right now, and when she talks about the books, it takes me a minute to figure out what she’s talking about, because she has totally different ways of pronouncing the “Wizarding World” vocabulary, right?

In terms of their ability to roll with not knowing, kids are actually the most flexible and accommodating of readers, so I didn’t feel like I had to explain things. There were some moments where I made some translation decisions with potential harm in mind. There is a phrase in the book that is downright racist in Greek, and it translates in a way so that I could change it to something that was not racist in English.

Another issue was that there’s so much color-coding in the book—black is a bad color in the story, because the Blackshirts were the fascists. That troubled me, so I relied on a “focus group”—I had a whole bunch of readers, including young readers, who were the children of my friends. For example, I read the book to my daughter out loud, and I read it to her cousins. And when they would get tripped up on things, I would ask them, “What does fascism mean to you? Like, is this a meaningful word?” And then they would always say, “Can you just read the book?” That made me realize that my concerns are the concerns of an adult who wants to make sure that certain messages get through without the interference of not-knowing, but the kids are getting the messages just fine. Actually, I could just relax.

TU: A common refrain throughout the book is the sisters’ made-up phrase—"veha/vesa”, referring to their mood as either happy or sad. Is that the phonetic phrase from the original text or did you change it for English audiences?

KE: I changed it; in Greek it’s “evpo/lipo” [i.e., ευτυχισμένη πολύ (very happy) /λυπημένη πολύ (very sad)]. The previous translation had it transliterated as evpo/lipo. That was something that I wanted to do differently. I don’t think it’s ever explained in the book, and it’s just not meaningful [without the Greek context].

TU: What do you hope English (and young) readers get out of The Wildcat Behind Glass, especially since this period of Greek history is not well known to most Americans?

KE: My primary desire is for young readers to read the book. And also, I hope people read the book at all ages. Anyone who reads it can think about how easy it is to slip into fascism, because you see daily changes that are very recognizable, and especially in our current times. I hope that readers will reflect on how easy it is to normalize a move to fascism that we know from history can go toward very bad places, very quickly.

Karen Emmerich is a translator of modern Greek literature and Associate Professor of Comparative Literature at Princeton University. Her translation awards include the National Translation Award for Ersi Sotiropoulos’s What’s Left of the Night, the Best Translated Book Award for Eleni Vakalo’s Beyond Lyricism, and the PEN Poetry in Translation Award for Yannis Ritsos’s Diaries of Exile (co-translated with Edmund Keeley). She has also translated books by Kallia Papadaki, Christos Ikonomou, Sofia Nikolaidou, Amanda Michalopoulou, Margarita Karapanou, Miltos Sachtouris, and others.