This essay is a short excerpt from a long essay of the same name published in The Delos Symposia and Doxiadis, an anthology of architecture essays published by Lars Müller Press edited by Mantha Zarmakoupi and Simon Richards.

On December 5, 1966, within the ornate chambers of the United States Capitol, Senator Abraham Ribicoff called the Senate Subcommittee on Executive Reorganization to order. Nine senators sat at their elevated desks, examining the celebrated figure sitting before them. Besides Ribicoff, one other lawmaker was intent on making the most of this hearing. This particular senator wanted to know what their guest—this world-famous architect and city planner—could do to address the urban crisis then afflicting cities in the United States.

Ribicoff leaned into the microphone: “Mr. Doxiadis, you may proceed as you will. Go at your own pace […] after you are through, we might have a few questions.”

“I consider it a great honor, and a great challenge,” Constantinos A. Doxiadis replied. The Athenian architect was fifty-three years old, and is impeccably coiffed hair and mustache had begun to gray. In many ways, Doxiadis had reached the pinnacle of his career. By this point, a constellation of institutions based out of his headquarters on the slopes of Athens’s Mount Lycabettus brought business, education and cultural outreach to the city and to those who came to study Doxiadis’s planning theories in Greece. These organizations included Doxiadis Associates, his architecture and planning firm employing 700 draftspeople, planners and engineers; the Athens Technological Institute, his undergraduate and graduate school in planning; and the Athens Center for Ekistics, his think tank, as well as Ekistics magazine, his scholarly journal spotlighting exciting developments in the field of human settlements. Additionally, by this time the Delos Symposia, Doxiadis’s human-settlement-themed conference cruise on the Aegean, had run for its third year, in the process becoming a noted event for intellectuals the world over. Six months earlier, Doxiadis had been given the Aspen Award in Colorado for his lifetime of work on human settlements in at least forty countries; by the New Yorker’s estimate, his work had already impacted the lives of 10 million people.

“I was impressed by your letter to me,” Doxiadis told Ribicoff. “One thing you said was: ‘We don’t know enough about the problems; we know even less about the solutions.’ Allow me to support that statement […] I can only add that, because we now have the courage to make such admissions […] we are beginning to learn.” Immediately, Doxiadis entered into a detailed, eloquent twelve-point description of his life’s work – his design philosophy of Ekistics, the science of human settlements; his findings derived from a lifetime of studying and planning communities around the globe. In the course of this “lecture,” he shared his firm’s maps; his drawings of the five elements; his iconic, often comical, sketching style. It was a lecture he had given many times, and it was hardly the first time he had given it in Washington, DC.

Georgetown was the home of Doxiadis’s American headquarters, along the historic Chesapeake and Ohio Canal. Noting the high-speed water taxis in operation at the time in Venice, Doxiadis was of the opinion the same might be useful for Washington, since the Potomac River linked Maryland, Virginia and the District of Columbia, and therefore might be the perfect vehicle to shuttle commuters back and forth between their various shoreline communities. “The river is a cheap, ready-made means of transportation that will cost nothing to maintain,” Doxiadis had told a Washington newspaper in 1958—a sunny suggestion few took to heart.

But, as Doxiadis went through his projector slides—his drawings of cities expanding; ballooning; intersecting in wavy, curvilinear forms—the interested senator, who had been listening so intently, could not contain himself any longer.

“Could I see the last painting again?” Senator Robert F. Kennedy of New York asked, in his iconic New England accent. “Did you do that yourself?”

“Yes,” Doxiadis said—they were indeed drawings by his own hand, and he said as much to the brother of the beloved American president who had been slain three years earlier in Dallas, to the man who would run for president in two years, the man who would then be assassinated in the kitchen of the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles. Here and now, Robert Kennedy allowed Doxiadis to continue for a few more minutes, before the senator interjected again:

“Could I just interrupt? I know it is wrong of me, but I don’t understand some of this.”

In that moment, out of this interruption, something remarkable happened. Over the course of the next hour—more than thirty pages of transcript—Doxiadis and Kennedy traded their opinions on the state of cities in their time: the problems of urban decay, of the failure of public housing, on how to provide a future for many minorities left behind in cities while more affluent white populations fled to the suburbs.

Repeatedly, Kennedy asked Doxiadis: What would he do? How would he do it? Finally, when Doxiadis concluded with his points—and his responses to Kennedy—Senator Ribicoff asked some questions himself: “Are you doing work for any cities in the United States today?”

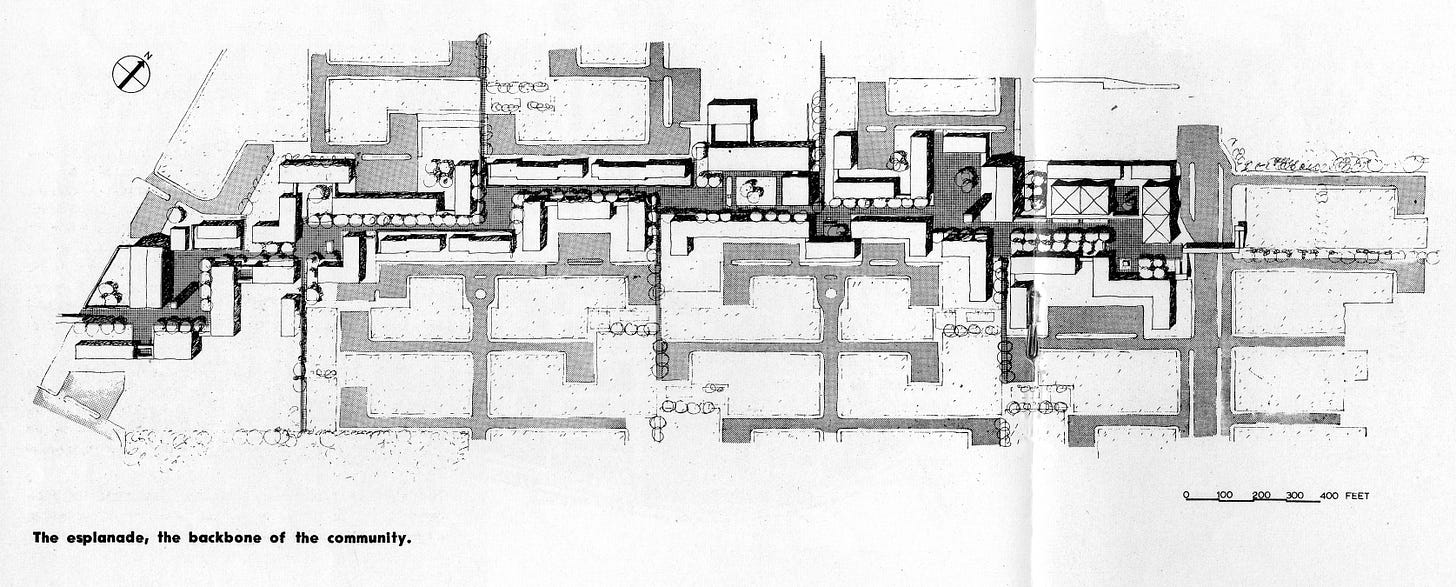

“Yes, sir,” Doxiadis said. “One of the urban areas we are working with is in the city of Philadelphia, where we have an urban renewal project to create a city within a city for almost ten thousand families. It is called the Eastwick area, and there we try to carry out the principles of communities in a human scale”

Several minutes later, as the committee was just about to adjourn, Kennedy would speak up once more: “Mr. Doxiadis, I am going this afternoon to Philadelphia to see your project […] I have heard of it and some of the other work that is being done in Philadelphia, and I wanted to look at it and see whether we can do something like that in the city of New York. I am looking forward to it.”

Fifty-two years after Robert Kennedy said he would visit the Eastwick neighborhood of Philadelphia, I did. It was a bitterly cold weekend day in March 2018 when I took the pitted I-95 south from Princeton to the City of Brotherly Love. I drove through downtown, past City Hall and the Comcast Tower; I drove up and through the double-decker, trussed Girard Point Bridge, crossing the Schuylkill River. I took the exit for Penrose Avenue, entering the district of Eastwick, though there are few signs announcing the fact. From a metropolitan standpoint, the area’s most important amenity is Philadelphia International Airport (PHL). Outside of the airport, one can find industrial sites, landfills, strip malls, a public library branch and a SEPTA suburban-rail station that can take you out of this somewhat forlorn place and back downtown. There are even still the original phases of rowhouses planned and designed by Doxiadis Associates, the subsequent houses built and designed by later development corporations—though you would never know that, if you weren’t familiar with the history of Eastwick. This is astonishing, because in the 1960s this neighborhood was the site of what was the largest urban-renewal project in US history, its cost a whopping $78 million—the equivalent of more than half a billion dollars today. Eastwick was so nationally prominent, it was even floated as the location for a failed bid to host the 1972 Olympic Games. And yet, this is not a historic planned community, like Frank Lloyd Wright’s Usonia, New York; or the original Levittown in Long Island; or James Rouse’s celebrated Columbia, Maryland. There are no signs.

On this cold March day, the only way I could deduce I was in the right place – that I had entered the network of a Doxiadis plan—was through the street layout, which was highly engineered. The streamlined collector roads made it extremely difficult to enter the residential neighborhoods. Again and again, I was steered onto other major streets, pushed in the direction of the highway, down one-way streets and circles that led to empty blocks covered in weeds and trash – abandoned and deteriorating housing; the borders of the marsh, where all this had been built. Finally, after more than an hour of navigating this labyrinth, I came into a neighborhood that had, in many ways, held up relatively well. One house even had solar panels. Here, I finally stopped.

About 12,000 people live in Eastwick. The median household income is $39,000 a year —for a Northeastern city, this is a lower-income area. The neighborhood is 76 percent African American. Like some other parts of Philadelphia, it is a place frequently tested by violence—with eighteen reported homicides from 2010 to 2017.

The gulf between Doxiadis’s high-minded rhetoric of Eastwick and the disappointing reality is stark and demands explanation. For a moment, consider Doxiadis’s background. The Athenian was no stranger to working in less-than-ideal conditions— in Greece, he had led a resistance group against the Axis Occupation; in Iraq, his team of architects survived a coup d’état; in Pakistan, he had realized an entire capital city from the ground up. Doxiadis’s efforts in Eastwick were no less ambitious—and in some ways, perhaps they were even greater. Despite the praise of its initial residents, the redeveloped Eastwick never took off, and today, to the untrained eye, it appears an unremarkable, low-income suburb on the fringes of the Philadelphia Airport. What happened to Eastwick? The answer lies not in the idealistic vision of its international master planner but in what his dream ran up against. At the heart of Eastwick’s disappointment was a deep-seated American phenomenon: the racial prejudice of its prospective inhabitants.

Read the rest of the essay in The Delos Symposia and Doxiadis, available now from Lars Müller Press (and for a better price in the U.S., on Amazon).

This is the sixth essay in The World Planner series, chronicling my biographical investigations into the life and times of Constantinos Doxiadis. These pieces take longer to write than the other posts, so they’ll appear on an intermittent basis.

If there are stories you would like to share about Doxiadis for inclusion in my work, please write to me at doxiadisbiography[at]gmail.com.