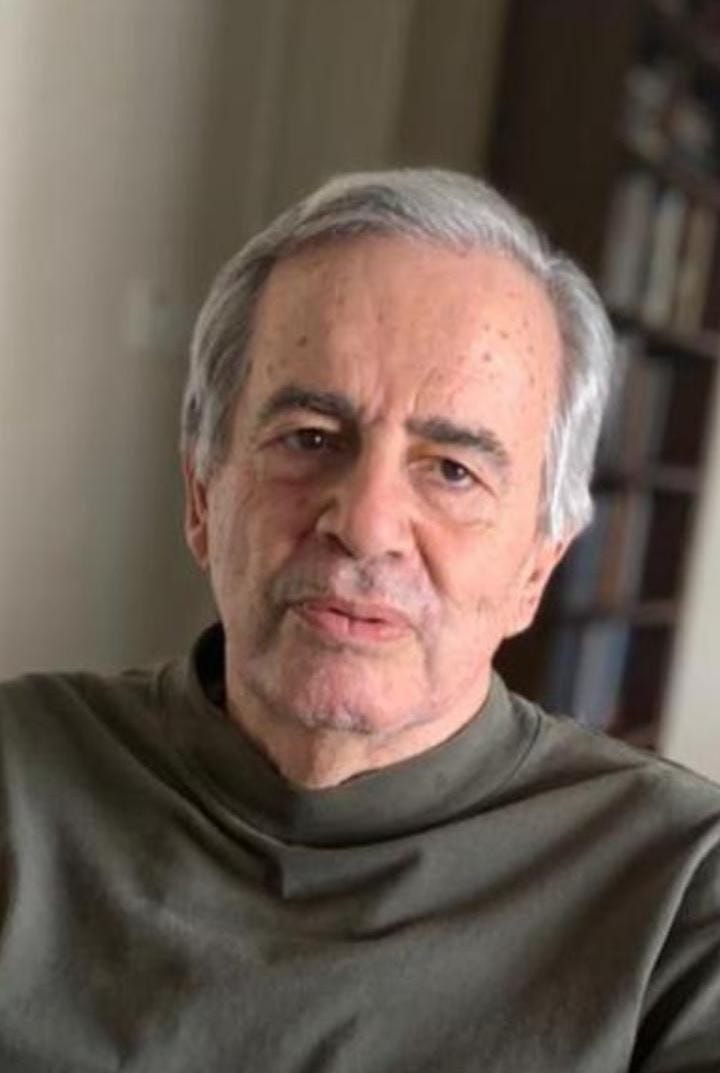

Cypriot poet and writer Stephanos Stephanides on "The Wind Under My Lips"

A work of poetry and memory fiction

In each installment of “The Usonian Interviews,” The Usonian spotlights a storyteller or artist from a different corner of the globe. And in each issue of The Cyprus Files, we explore another corner of the Island of Aphrodite. This piece is an exciting crossover edition of both newsletter feeds.

This week, The Usonian spoke with Cypriot poet and writer Stephanos Stephanides about his book The Wind Under My Lips, a work that juxtaposes poetry with “memory fiction,” a hybrid form of memoir.

Though the book is hard to find, you can purchase the book on Amazon or directly from the the book’s publisher, To Rodakio, in Athens, Greece.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length. The views presented by the interview subject are the opinions of the subject and do not represent the views of the author or this newsletter. Browse the full interview archive here.

THE USONIAN: Let’s talk about the title. The Wind Under My Lips is a reference to the Ezra Pound poem, “De Aegypto.” What drew you to that line? How does the book connect to the poem?

STEPHANOS STEPHANIDES: I really like Ezra Pound. I like his short lyrics and his early poems. When I was rereading him, this [poem, “De Aegypto”] struck me. And then, in my own cultural memory, Alexandria is quite significant. It’s where my paternal grandfather is from, who I was named after. The line also seemed to capture the way I write memory. The city resonates with Cavafy. It’s like, there you feel it and you can’t quite catch hold of it—in the sense of “semantics of senses.”

TU: Speaking of memory—this book combines poetry, and prose sections that you characterize as “memory fiction.” How do you define memory fiction? Tell me about how the book developed and came together?

SS: First of all, it’s not really autobiography as such. It’s more of a memoir, but then a memoir also has conventional boundaries. So I didn’t want to call it a memoir. I thought of “memory fiction.” The term stuck with a lot of people in the sense that they always ask me about it. The fact that you’re writing a memoir creatively means that there’s always that aspect of passion and the processes of inclusion and exclusion, and how do you reimagine it? It’s always on that boundary, because, especially when you’re going around back to early memories, I’m reshaping from what I remember now, and sometimes I might invent dialogues.

TU: Which any memoir does.

SS: Right. I don’t really know what was said, but it’s very likely that this is how I remember the people and this is how they would have spoken. Also, it’s the afterlife of memory, and how it resonates with me. [This] is behind all of creative writing.

But I think this [book] grew out of the poetry in the sense that when I was writing poems, and when I was doing readings, I would often tell stories behind the poem. And people were really interested in the stories.

I thought maybe I should really write them down as well. And then when I started writing down the stories of the poems, it just grew on its own. Initially, I didn’t feel I was into the narrative form. And then I began to intertwine it with poetry because they organically belong together even though they seem to be different genres. Why should we have boundaries in genres? We keep reinventing genres and their boundaries anyway.

But I didn’t really have any concept of the book as a whole. In fact, [the book was made up of] fragments that I wrote over years, and published them in different places, without any final intent. It was in effect, bringing various pieces of mosaic, and then shaping it and putting it together as a book. I don’t think I have that kind of mind where I’m going to do a book and then I am going to plan it out at different stages. I’ve never been able to work like that, even in my academic work.

TU: In the poem, “Rhapsody on the Dragoman,” the speaker says, “I am a dragoman,/ courtesan of the word.” The readers of this blog might not know what a dragoman was. Could you explain what that term means, and how the speaker identifies with it? And if that relates to your own relationship with the written word?

SS: In many respects, I see that as the signature poem of my persona as a poet. I became a translator at an early age. Let me explain the word dragoman. The dragoman derives from the Arabic, tarjumān. That’s also gone into Turkish, meaning translator, but beyond that, a dragoman was also a high-level officer during the Ottoman Empire, representing the religious minorities like Greeks, Armenians, and so forth in the Ottoman Empire, where they mediated between the ruling class and that community. So it emphasizes the mediating and diplomatic functions of what translations are all about.

Dragomans were very interesting figures as well. They had a powerful and dangerous role. They were representing both communities, but they could also get on the bad side of either, depending on how they played it.

I find all of this very interesting. Especially because of the way I grew up. My childhood language was the Greek Cypriot vernacular. And then I found myself in England rather suddenly, when my father grabbed me and took me there. At first, I was resistant to English, but because I was a child, I absorbed it very quickly. So being in-between languages was part of my life from the very beginning. That also shaped my perspective when I was in school. I was really interested in literature and other languages. I have been a teacher of languages, and also worked as a translator and conference interpreter. That mediating role has been part of my life all the time.

TU: We’re talking about languages. Greek is your language, but it’s not your literary language. Tell me about the decision to publish the book as a galley edition, with both languages presented side by side.

SS: My work has been translated into different languages and I felt that also living here, and being a Cypriot, Greek being the tongue of my mother, even though no longer my dominant language, I felt it needed a Greek translation and I found a wonderful translator in Despina Pirketti, who is also a former student of mine. [Since] many people read English in Cyprus, I thought putting them next to each other would make it very interesting and provide a double perspective.

Despina, in an essay she’s written about the translation process, she said in many respects, although she was translating, she felt she was translating back to my mother tongue that was absent. Unconsciously, or even consciously sometimes, my turn of phrase [in English] would reflect the cadences [of Greek]. Sometimes I deliberately make the English less idiomatic to allow the reverberations of other languages. The translation process makes you more aware of that.

TU: If you look at any poem in this book, such as “Sentience”, you’ll see brushstrokes like “rooftops, bell towers and minarets”— image-making, but without falling into conventional tropes. When you write about the Mediterranean, you call it the “Middle Sea,” which gives the name a different quality. When you’re writing about Cyprus, how did you choose to write about the island in these ways?

The underlying principle is the same as what I said about language. It is an attempt to open a vision beyond the way conventions and received opinions may lead us. I think it’s the role of poetry to break all of that and go into these other layers of meaning and bend and expand our perception of the world.

I want to convey the felt experience, rather than conventional rhetoric. When I was reading for the Commonwealth Short Story Prize, there were a few stories from Cyprus. And of course, you can never avoid this [island’s] division, which in one way or another we all write about. I wanted to find something different from the same old story. When I read, I want to be surprised and taken to another level where I am able to feel and think differently. Because otherwise your senses become numb and you get stuck in the same place, which is where we are politically—basically it sometimes feels like we are stuck in the same place forever.

TU: The prose sections are centered around the speaker’s relationship with Elengou, your paternal grandmother, and the village of Trikomo [also known as Yeni İskele]. I felt that relationship was a very moving part of the story, tragic at the end. Could you tell me a little bit about why that relationship is such an anchor?

SS: I think she was a key figure in my childhood. My parents separated when I was a very young age and they moved away from the village and they left me in the village. And looking back on it, it was kind of a blessing in disguise, because I experienced a rural way of life that has virtually disappeared. I mean, partly because of partition, but also because displacement radically changed the rural way of life. So, in looking back on it, I was very privileged to experience that world. I remember the introduction of piped water and electricity to the village.

Elengou cherished me as her eldest grandson. I stayed with my maternal grandparents, and [Elengou] was my paternal grandmother, but she was a great walker and a great talker. I would walk everywhere with her, to cemeteries, to buy milk or honey from whoever sold it, to visit her old teacher, even though she was in her sixties herself. I had that access to a whole culture through her. She told me all kinds of things—dates and names, sometimes family stories or the stories from Greek myths, or stories from the Bible—they all merged and intertwined in my imagination.

I remember it so intensely and vividly because I was taken away very suddenly, at the age of eight, and I was dumped by my father in industrial, dark Manchester, from this very rural Mediterranean village full of light in natural abundance. So it was something that I cherished. I associate this time with several people, but I think it was because she was a walker and a talker that made this whole early childhood narrative possible.

I also had that desire to go back to the village and then there was the partition, and by that time she was old and demented, she couldn’t even remember there was a partition, she didn’t know why she wasn’t in the village, and by the time I did visit Cyprus again she had passed away. In my early years, she was an iconic figure.

TU: I found the last section of the book very interesting—in which the speaker is teaching at the university, and he receives an email. This section captures the mundane day-to-day life of a professor, but then this lightning bolt out of the blue arrives, with this curious word that triggers something in the speaker’s imagination—

SS: The adropos [αδρώπος].

TU: Can you tell me like to define adropos, as well? What that means and how that moment captures Cypriot culture and history coming to the fore along with modernity?

SS: I mean, [the section is] written in a kind of crazy way. But the word adropos is the way that Cypriots pronounce anthropos [άνθρωπος, humanity]. Τhey tend to vocalize certain consonants. This invitation by Peter Εramian—he’s an artist and has installations and he was bringing out a journal, but at that time, I hadn’t heard of him. Although I now know, he’s quite well known in the artistic scene. He invited me to contribute a piece to a special issue on the concept of Adropos.

I found it a curious thing, and when I was an academic [I didn’t know if] I had time to deal with this thing, and who was this guy anyway, I asked myself. So this kind of crotchety tone I take at the beginning was also how if felt at the moment. And then I thought, well, maybe it’s a young person, I should be honored, let me try and get into dialogue with him. So the whole story began there. I wanted to talk to him more about it, but he wasn’t around, and the publication didn’t have an office. Then he put me on to someone else, the co-editor, who had the fantastical name of Entafianos Entafianos, which all sounded and appealed to my imagination. I felt it was all some kind of fiction.

Entafianos turned out to be a lawyer. [Eramian] said, get in touch with him and he’ll meet you and talk to you about the project. And he turned up with his lawyer suit and tie at the university. It all evolved quite fantastically from there, and I wanted to know the root of his name [Entafianos]. That was also a whole fantastic story because his grandfather was born in church on Good Friday—apparently, his great grandmother went into labor on Good Friday while they were in the church. And they thought, what will we call this child? They gave him this unique name because he was born in church on Good Friday. And as happens in Cyprus, it became a surname and then the child was named that.

So he took me to his village to visit the church and the cemetery and other places. I was playing around with the anthropological thing. And then I thought, well, it’s all real. This is a continuation of my memory fiction as well. The more I got involved and started talking to people it kind of cut into it. It’s written both as a kind of parody and pastiche but also with affection. It’s kind of contrasted with the more elegiac tone that I’d been using in the earlier memoir pieces. So it reveals another part of my personality and voice. And it was interesting how it came about through an unexpected invitation and also an unexpected opportunity. I probably wouldn’t have written that way [otherwise].

Stephanos Stephanides is a poet, essayist, memoirist, translator, ethnographer, documentary filmmaker, and former Professor of Comparative literature at the University of Cyprus. He was born in Cyprus and was taken to the UK by his father when he was eight. He returned to Cyprus in 1992 as part of the founding faculty of the University of Cyprus. He completed his PhD at Cardiff University. He has lived in Spain, Portugal, Greece, Guyana, the USA. He has where he developed a deep interest in Caribbean culture, and Indian diasporic communities. Selections of his poetry have been published in more than twelve languages. He has held residential writing and research fellowships at the University of Warwick, the Bogliasco Foundation, Italy; JNIAS at JNU, India, and is a writing fellow of the IWP of the University of Iowa. He was awarded first prize for poetry from the American Anthropological Association, 1988, and first prize for video poetry for his film Poets in No Man’s Land (2012) at the Nicosia International Film Festival. He was a judge for the Commonwealth Writers Prize (2000, 2010,) and for the Commonwealth Short Story Prize (2022). He is Emeritus Fellow of the English Association, and Cavaliere of the Republic of Italy. Representative publications include Translating Kali’s Feast: the Goddess in Indo-Caribbean Ritual and Fiction (2000), Blue Moon in Rajasthan and other poems (2005), and The Wind Under My Lips (2018). His ethnographic films include Hail Mother Kali (1988) and Kali in the Americas (2003).

Note: This piece was updated for clarity on 5 July 2022.

This is the twenty-fourth post in The Cyprus Files, a limited-run newsletter series from The Usonian chronicling my Fulbright experiences in Cyprus. You can read all the posts in The Cyprus Files here. Thanks for reading, and don’t forget to subscribe so you don’t miss a (free) dispatch from the island of Aphrodite!