Aaron Hamburger on "Hotel Cuba"

A historical novel about a remarkable story of immigration

In each installment of “The Usonian Interviews,” The Usonian spotlights a storyteller from a different corner of the globe. This week, The Usonian spoke with author Aaron Hamburger about his new novel Hotel Cuba (Harper Perennial, 2023). You can order the book at Politics & Prose here.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length. The views presented by the interview subject are the opinions of the subject and do not represent the views of the author or this newsletter. Browse the full interview archive here.

THE USONIAN: Your novel has an interesting origin story. Tell me about it.

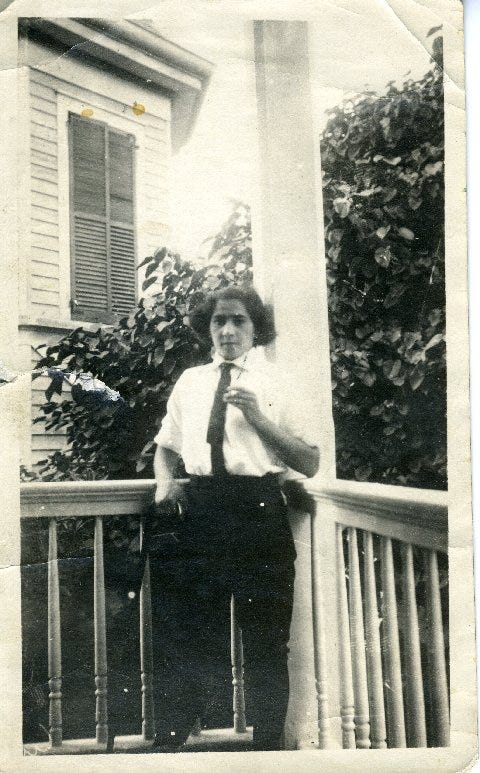

AARON HAMBURGER: About six years ago, I found this incredible picture of my grandmother in full male drag, dated 1922, taken in Key West. I grew up knowing my grandmother as the sort of traditional Yiddish bubbe, who was always very conservatively dressed, sang me lullabies in a thick Yiddish accent, baked cookies and fed me Hershey’s Kisses. So this image was totally surprising and discordant to me; I was very intrigued by it.

At the same time, I was very much thinking about the story of immigrants. Immigration was in the news, especially after the 2016 election. I started digging into my grandmother's story, and I realized she had been arrested for being an undocumented immigrant.

At this time, a group of writers were getting together on Capitol Hill to lobby senators for progressive causes. I went to visit Senator Debbie Stabenow of Michigan, the state where I grew up. I took my grandmother’s picture along, and I told her who I was, and I told her my grandmother’s story. I asked her to protect the rights of the immigrants today, in honor of my grandmother, and she replied that she agreed with me, 100 percent.

So I said, “Well, what can I do to support you in that?”

Stabenow said, “You’re a writer—tell your grandmother’s story.”

That was a very daunting ask. So I thought about it. I had not really written historical fiction, strictly speaking, before this time, but all every story that I write is very deeply engaged with time and place. I started toying with the idea in my mind—what if I could write this story?

I went to a reading by a local historical fiction novelist, named Dolen Perkins-Valdez, in which she talked about her process. She explained she wrote a draft to figure out what she needed to research. Her example really freed me, because I didn’t have to research everything that happened in the 1920s—I would just need to research whatever I’d need for the particular aspects of my story.

But it also freed me, on the creative end, to stumble forward blindly. Just plunge into the project, write it and see what happened, follow the story where it went. And then, you know, as I went along I would realize, oh, how did people make phone calls in 1922? Or, what did passports look like in the 1920s? I could look for the answers to those questions. And very often, in finding the answers to those questions, that would suggest plot possibilities that I could use in the novel.

TU: In this case, you knew the general outline of your grandmother’s story. So perhaps you weren’t totally writing blindly?

AH: My family has these recorded interviews with my grandparents that feature my grandmother telling her story. And it’s interesting because she narrated both the broad outlines of the story and then plugged in a few pungent, tantalizing details. There are these interesting gaps to fill in-between.

That gave me a roadmap to work with. I knew that she came from this shtetl in Russia and that she faced the horrors of the Russian Revolution and World War I, plus anti-Semitic pogroms, famine, and poverty. I knew she wanted to get to the United States. But the immigration laws had changed, and she could no longer get in. Instead, she went to Cuba with her sister.

I also knew that her sister had managed to get into America before my grandmother, by paying an American couple to pretend that she was their daughter. My grandmother tried the same thing and was arrested in Key West. I had that all that to go on.

As I wrote the story, I started thinking about, how would you practically accomplish these tasks? Like you’re in a little shtetl in the middle of landlocked Russia, in a war-torn landscape? How do you physically get from there to Warsaw (which is where she had to go to try to get her visa).

I did research into the time period, and I learned that after the war the whole landscape was bombed out, a desert wasteland. You don’t think of Russia as being like a desert, but that’s what it looked like, right? The train stations were totally destroyed. You had to travel by horse cart to get to one of the stations that was actually in operation. And then you once you arrived at the station, the station might not have a roof. You had to wait in line to get tickets, and everybody’s pressing and pushing to get the tickets and money would have no value—we complain about inflation now, but if you had Polish money, it would be worth nothing. So you needed to pay in USD. Figuring out all these kinds of little details can help the reader to feel as if they’re living the experience along with the characters.

TU: In regards to the specifics—with a lot of the episodes in the book, it felt like it was coming from something that really happened, such as Pearl’s arrest in Key West. When things are that specific, they can feel like they’re not imagined.

AH: I always say it’s like building up the bank of authority that the writer has with the reader.

I got a really interesting question about the book when I was in New York. Somebody said, “I noticed you wrote this in present tense.” And that was something that felt like the right thing to do. Tense and point of view are like alchemy—they work because they work.

But there is kind of a method to that madness, which is that when you’re writing in the present tense, you’re emphasizing that this is not being written from the point of view of hindsight, this is being written from the point of view of somebody who’s living it. They don’t know how the story is going to turn out. Looking back, we know, this happened and that happened. But these people were living through it—they were very confused and didn’t understand what was going to happen next. So there was a lot of suspense, just as there is suspense in our daily lives today.

TU: I wanted to discuss the opening. You start with Pearl and Frieda on the ship, but then you use that frame for a series of flashbacks and almost elliptically give us all the backstory we need about Pearl and her trauma. And then we’re in Cuba, in the new context. Tell me about how you came to that structure.

AH: I once heard the writer Claire Keegan speak about the nature of fiction. She asked, “What is fiction made up of?” And you know, she’s asking this audience of Americans and we’re all saying “character and plot,” but in her very Claire Keegan way, she’s like, “No, no, you’re wrong. Fiction is made up of time.” And she said, in real life, time is infinite in both directions. What a story does is create this arbitrary starting point and this arbitrary endpoint and the space in between creates a kind of shape.

That shape is your story. So the question of where the story begins a difficult, important question. I always envisioned her on that boat coming across. And if I had started the story when she was born, or when she was nine, or when Frieda was born,—it would have created a different kind of shape. Because the way we think of shape in terms of time, the more that you stretch out time, the less drama and suspense you have in a narrative.

If I were to extend that time period over 10 years, it would create these spaces that have to fill in as a writer. So I wanted to definitely tighten that timeframe and give people what they needed to know about the past.

There was some other material I was thinking about including, but that ultimately ended up on the cutting-room floor because I wanted the readers to know only what they needed to know, to get Hemingway’s famous “tip of the iceberg effect”—where you receive just enough detail to suggest all the other stuff that you’re not getting directly.

That way you have enough information to understand, who Pearl is and where she’s coming from. Pearl is both a child and a mother; she was nine years old when her mother dies in childbirth, and she has to raise her baby sister.

It’s left her in this kind of space where she can’t really be herself. Because she’s so busy helping her family to survive.

I was interviewing my cousin, who is the son of the person who inspired Frieda in the narrative. He said to me, if the Holocaust had not happened, we would think of that time period as the Holocaust.

World War I and its aftermath was so awful, we simply can’t imagine how terrible it was. That’s his opinion, but it speaks to both the horror of the Holocaust, and the scale of it that it has the power to dwarf the horrors of what happened before.

TU: Pearl is a character who at the start of the story is very competent. But at the outset, she’s not fully activated in terms of being her own person and pursuing her own interests. You track that evolution very carefully to the end of the novel, when she’s finally taking charge of her own affairs. How did you demonstrate that change and work that through?

AH: My grandmother was known as a very strong-willed person. And that came through definitely when I was listening to these recordings of her interviews. There was one part where she had a fight with a relative. And she calls her machashefa, which I included in the book—she repeated his word several times. which means a “witch.” She’s basically calling her cousin a bitch. At first I was thinking that was her character.

I realized, at least for dramatic purposes for the book, that’s how she ended up. But how did she get that way? I tried to imagine somebody who was not quite that strong in her own skin. Having been confronted with these major choices, and navigating the best that she could, in the process of doing that, helping her to grow and self-actualize. That shows up in a lot of the little choices that she made throughout the book.

I also thought of her as a creative artist through clothes. At the beginning of the book, she has the skill for making old-fashioned, dainty clothes. And then she’s making clothes to make a living. She starts to develop her own sense of a more contemporary design aesthetic, which include pants for women. That was one of the ways that helped me to track her journey as a person, her development in terms of her personality.

TU: Tell me about your fieldwork in Cuba.

AH: It was in April 2017. There was so much serendipity happening around that time. My grandmother’s picture, that visit to the Senator and then my husband had a job for work that where they had to visit Cuba to look at the health system. And spouses could go along, and we could be tourists, but we had to pay our own way. So while he was going to every dental clinic in Havana, I was with the spouses and we had a really wonderful tour guide.

She took us around to various places, and everywhere we went, I really had my eyes open for anything that was older than 1922 because my grandmother might have seen that or might have walked there. The places where the Jews would have been at the time were in the old town of Havana, which is where all the tourists go anyway.

We were walking in those places where she would have been; while I was there, I was really trying to get a sense of atmosphere in terms of the architecture and what it was like to be in Havana but also the light, the heat, the smells in the air, the flowers, the sky. Thinking about what it felt like to move through those spaces and how it might have felt for somebody coming from dark, wintry Eastern Europe.

Our guide was so wonderful because she would tell us stories about her own family and her grandmother. There was one story she told about her grandmother going window shopping at the fancy department stores, and that made me think, maybe because my grandmother loved fashion, Pearl would have loved taking a stroll when she had a break, and maybe she would have looked at the windows of the grand department stores in Havana at the time.

TU: We talked about beginnings, and as we wrap up, let’s talk of endings. Without spoiling anything—at the end of the book, there’s a new stasis between our characters. But it’s also clear that not everything is resolved, and that there are more conflicts on the horizon. In the Afterward, you allude to some of that. Tell me about how you chose to stick the landing.

AH: In an earlier draft of the book, I tried to take the book all the way up to the Cuban Missile Crisis. And at the point where the book ends, I had a coda set 40 years in the future, explaining a lot of things that had happened. First of all, all the people in the village where they came from in Russia were killed in the Holocaust, which casts a certain shadow on the events of the novel.

But the problem is that it dramatically it didn’t work. The time created these gaps that I needed to fill, and there was no way to fill them in a way that felt satisfying, without turning this into War and Peace, which it is not.

These families left everything they knew, and all they had was each other, and that put so much pressure on the family. These differences that might have been relatively minor, became magnified, because they were on top of each other. My grandparents and their siblings built and lived in a house together, in addition to owning a business together. And they were almost like one family.

In the recordings, my grandparents said that their siblings became “the kind of people who played cards.” They began moving in different social sets. They had different values. It all came to a head in a very dramatic way, and they had this falling out. At this point in the interview my grandfather burst into tears. My grandmother said she went over to see her sister and told her off. And my brother asked her, “What did you say?” And my grandmother said, “Not nice words.”

That is the actual story of of what happened. It’s an interesting angle to inform this tale, because Frida and Pearl are so close, but you can also see how they’re different people and how it might not last.

Aaron Hamburger is the author of four books, the story collection THE VIEW FROM STALIN’S HEAD winner of the Rome Prize in Literature, and the novels FAITH FOR BEGINNERS (a Lambda Literary Award nominee), NIRVANA IS HERE (winner of a Bronze Medal in the 2019 Foreword Indie Awards), and the newly released HOTEL CUBA. His writing has appeared in The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Chicago Tribune, Tin House, Crazyhorse, Boulevard, Poets & Writers, and O, the Oprah Magazine and many others. He has also won fellowships from Yaddo, Djerassi, the Civitella Ranieri Foundation, the DC Commission on the Arts and Humanities, and the Edward F. Albee Foundation. He teaches writing at the George Washington University and the Stonecoast MFA Program.