A conversation with literary translator Jennifer Shyue

Meet an artist who travels across literary borders in Cuba and Peru

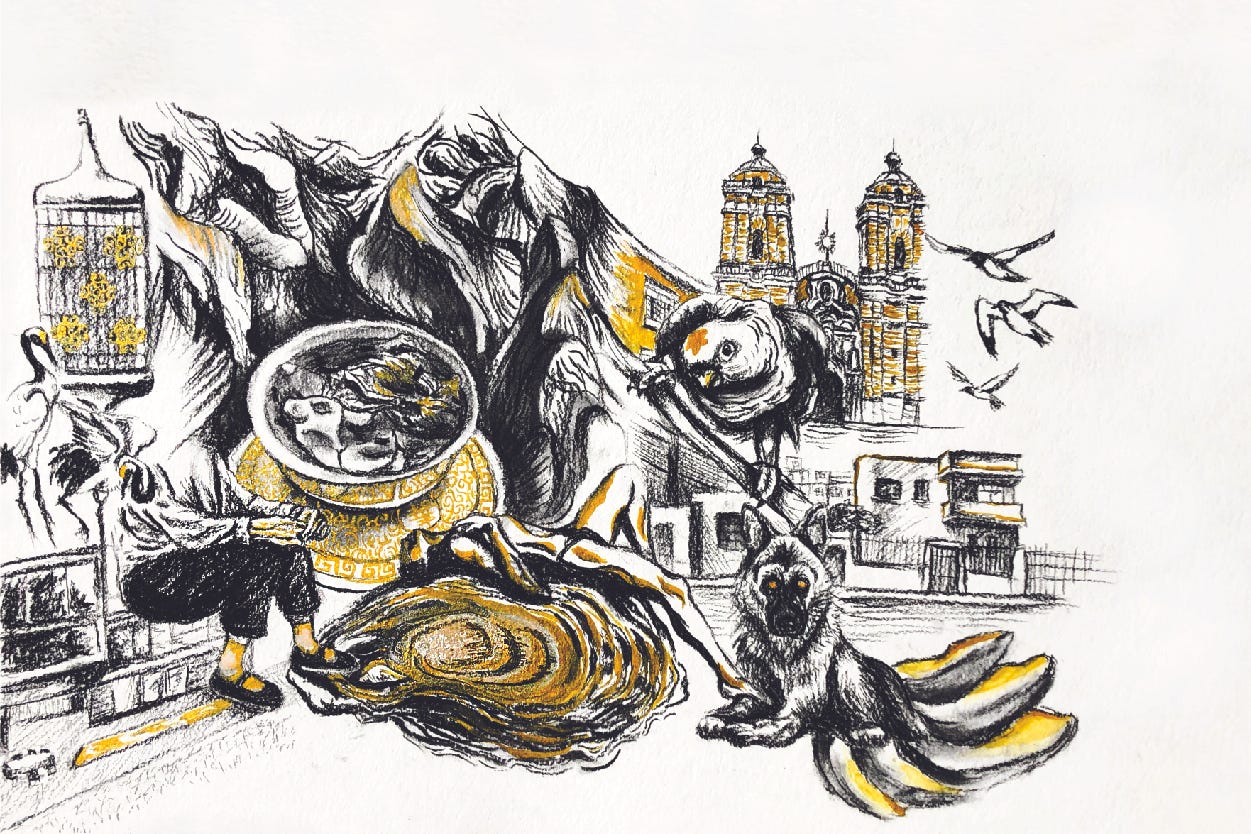

In each installment of “The Usonian Interviews,” The Usonian spotlights a new storyteller or designer from a different corner of the globe. This week, The Usonian spoke with Brooklyn-based literary translator Jennifer Shyue about her work translating Spanish-language fiction, verse, and essays by Cuban and Peruvian authors into American English.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length. The views presented by the interview subject are the opinions of the subject and do not represent the views of the author or this newsletter. Browse the full interview archive here.

THE USONIAN: Let’s start from the beginning. Why did you want to be a writer? Or, what made you interested in translation in Spanish?

JENNIFER SHYUE: Well, my way into writing is not that different from anyone else’s. But in terms of translation, that has a very clear starting point. In undergrad, sophomore year, I took a workshop with Natasha Wimmer, the great Spanish-English translator known for her translations of Roberto Bolaño, Álvaro Enrigue, and other writers. That was my first exposure to literary translation. And I was hooked, because it was so fun. It was all the best parts of writing. When you’re in it, it’s like a puzzle—I really like that. I translate from Spanish, because it’s the language I’ve studied since I was in middle school. I also speak Mandarin as a home language, but I never took literature classes in Chinese until college.

Formative moments would be spending time in Cuba and Peru. I did a gap year with the Novogratz Bridge Year Program, before undergrad, in the Sacred Valley of Peru, and then studied abroad in Havana for a semester, and then have since gone back to both Cuba and Peru, Peru most recently for a Fulbright that was cut short by the pandemic. So those countries are my two areas of specialty.

TU: That feeds into one of my questions about Latin America; every country has a totally different situation. What are the challenges of interpreting a Cuban literary tradition versus a Peruvian tradition?

JS: One challenge with Cuban literature is that it can be really hard to get your hands on the books from when you’re not in Cuba. What’s published on the island doesn’t really make its way past national borders. Though obviously there are Cuban writers outside of Cuba who are publishing outside of Cuba, and then there are also Cuban writers in Cuba who are publishing certain books that wouldn’t fly in Cuba, with presses in Spain—or in the Netherlands; there’s this one press [Bokeh], in the Netherlands, that’s published a lot of important writers. Getting your hands on books is not that easy for Peruvian literature, either. Once books go out of print, they’re often just out of print. Then you have to look for used copies, which is harder when you’re outside of Peru.

TU: Let’s talk about your translation process. Do you have two documents open at a time? How do you tackle this puzzle?

JS: I have a little book stand, because I got tired of trying to press down the book with one hand and type with the other. When I do have digital documents, I will have the two documents side by side. I prefer working with physical books, although it’s also really nice to be able to search in a document when you have the digital copy. So ideally, I’ll have both the physical and the digital versions. I find it much easier to read Spanish on paper.

I’ll actually have a lot of documents open. I keep two different separate documents outside of the main document. One of them is what I call a “Translation Memory”—even though there’s no translation technology involved—where I just keep an alphabetical list of how I’ve translated different words, so I can be consistent throughout whatever the work is, whether it’s a poetry collection or a short story. Then I have another document that’s called “Cut.” I don’t know when I started this habit, but I've always had it, where things I delete from the main document I’ll keep in this metaphorical drawer of remnants. It doesn’t come in handy that often, but sometimes it does. Like yesterday, I was doing some edits on a poem, and in that remnants document I found a word whose existence I had forgotten about. So that makes all the probably unnecessary copy-pasting worthwhile.

And then, in terms of drafts, I’ll try to do, not a totally rough draft, but I’ll churn through the words and just slap down what comes first. Often I get caught up in different definitions or thinking about sound on the first round, but I try to remind myself I will come back with fresher eyes later. That process is often really slow, because I’m also doing the “Translation Memory” document where I’m tracking basically every word and how I’m translating it. Once I have a full draft of the unit, whether it’s a poem or short story, I’ll leave it for a while. In maybe a couple of months, I’ll come back to it. And it’s like magic. I suddenly see all these things that were terrible choices, and I can fix them. That’s probably my favorite part of the process because I’ve already built the base and I can get in there and start to play with things, which is really fun.

TU: Who would you say are your influences, in translation, or in literary style?

JS: I really admire translations of poetry where you can really see the translator’s hand at work. Especially for me, I sometimes feel like I’m very much groping around in the dark with poetry because the last time I had formal training in poetry was high school AP Latin, when we learned all the rhetorical devices that were in The Aeneid. A lot of my poetry translation feels like it’s done by instinct, and then I get nervous, and I’m like—gotta stay close, or can’t go too far. But translators who make choices I might not have thought to make but that really make sense are always ones I admire. Recently I’ve been looking at Olivia Lott’s translation of Katabasis by Lucía Estrada, and other translators like Yvette Siegert. Margaret Wright, our classmate [at Princeton], translated some poems for the Words Without Borders issue on Peruvian writers of Asian descent that I edited last fall. It was so great to look at her translations, because she made some beautiful choices that I still think about. That inspired me to be braver in my own choices. I guess that’s what translating poetry requires—being brave.

TU: How do you find authors you want to work with?

JS: I have been lucky to have people who put books in my hands that I ended up loving. I remember at the Havana Book Fair in 2016, my friend Adriana put a collection of poetry by Legna Rodríguez Iglesias in my hands, and I ended up really loving it. I’ve since translated Legna’s novel in verse, which is one of those novels that was never published in Cuba; it’s only been published by that one Netherlands press.

When I was in Lima on Fulbright, one of my first stops was this really lovely little bookstore called Escena Libre. The manager Julio put a lot of books in my hands, and one of them ended up being a short story collection that I’ve translated a couple stories from. I just love going to bookstores. There are so many good bookstores in Lima.

TU: Yeah, they are so much better in other countries when they’re not Barnes & Noble.

JS: (Laughs.) You don’t know exactly what’s there, because it’s not all catalogued. But it’s really fun to just look.

TU: What’s something that you're working on right now that you’re excited about?

JS: I’m editing the poems that will be in a chapbook that’s coming out from Ugly Duckling Presse’s Señal Latin American poetry series. I just had my last session of queries with Julia Wong Kcomt, the writer, and that was really fun. Working with her is great. I love her poetry, and she’s also so generous with answering all my questions and often unlocking the poems for me in a way that I appreciate.

TU: Have you read anything that you enjoyed lately?

JS: The Office of Historical Corrections,by Danielle Evans—that was great. I loved The Magical Language of Others, the memoir by E.J. Koh. Mother-daughter narratives are really up my alley. On that front—Vivian Gornick’s Fierce Attachments. That’s something I enjoyed recently. And Hurricane Season, by Fernando Melchor, translated by Sophie Hughes—the way it upends your expectations with every chapter. As soon as I finished it, I wanted to re-read it.

TU: Do you have any advice for young people who might want to become literary translators? What would you recommend that they do to pursue this?

JS: I think time is magic when it comes to translation. This is true for writing as well, but maybe because it can be so hard to unstick yourself from the original while you’re looking at it, if you let yourself forget both the original and your translation for a little bit, you come back and it’s like, sometimes I’m like, how did I ever think this word choice was a good idea? It’s very obvious what needs to change. In college I never wrote any papers before the day they were due. But now I’m a big fan of time’s effects on the revision process.

I got a lot out of my MFA in Translation at the University of Iowa. You get a lot of years of growth crammed into two years. And most students are funded—that’s not true of all MFA programs. If you have the ability to spend two years focused on translation—for me, it was helpful.

TU: I enjoyed your personal essay “Mother’s Tongue” in The Common. In it, you discuss aspects of your identity as a Taiwanese American who works in Spanish translation. You also asked, who does American English belong to? So, who do languages belong to? How do you see your role as a translator, communicating between these various literary traditions?

JS: To whom does a language belong? I think English is maybe a particular case, because so many people have been forced to use English, whether by necessity, or because of the fact that it’s a global lingua franca, because of cultural exports and imperialism. For English, I would be inclined to say it belongs to everyone who uses it.

Regarding my role as a translator, there is one metaphor I saw on Twitter a while back, that was for translating specifically into English: “It’s like giving the writer of the original text the stage of English,” which I think is interesting and indicative of English’s particular status.

TU: You wanted to talk about the name “Usonia.”

JS: I hadn’t come across Usonia as a concept before encountering it in your newsletter. I do think it is an issue that we’re so content to think of America as just the United States. In lots of other parts of the Americas, América refers to the whole continent [North and South America together], right? And if you wanted to say “from the U.S.,” you would say norteamericano, not just americano. Usonia as an idea is very intriguing.

Jennifer Shyue is a translator focusing on contemporary Cuban and Asian-Peruvian writers. Her work has been supported by grants from Fulbright, Princeton University, and the University of Iowa and has appeared in A Perfect Vacuum, The Arkansas International, Spoon River Poetry Review, and elsewhere. Her translation of Julia Wong Kcomt’s Bi-rey-nato is forthcoming from Ugly Duckling Presse’s Señal chapbook series. She can be found at shyue.co.