The great California novel

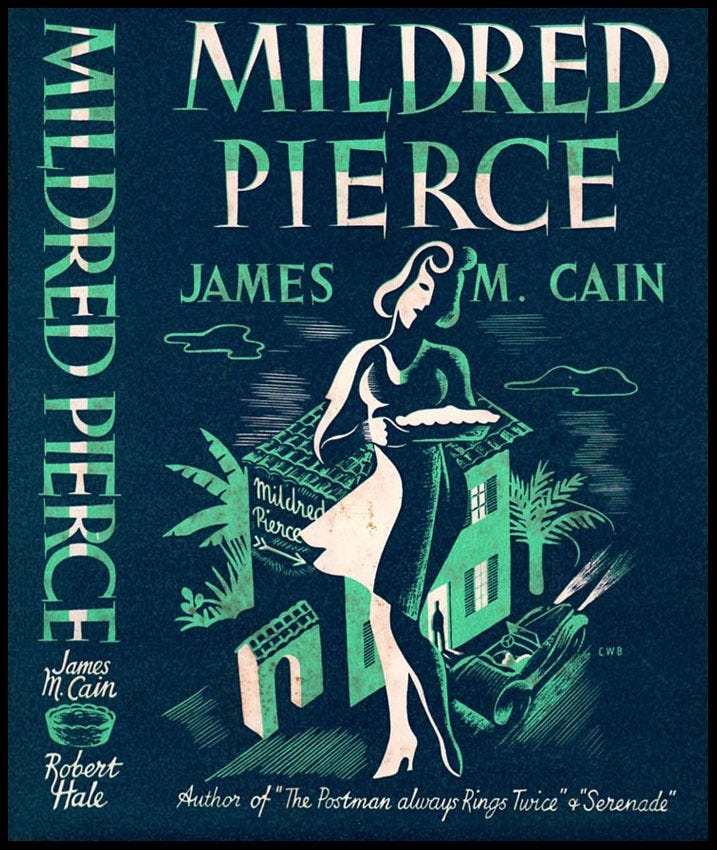

Narrative Architecture #4: James M. Cain's "Mildred Pierce" (1941)

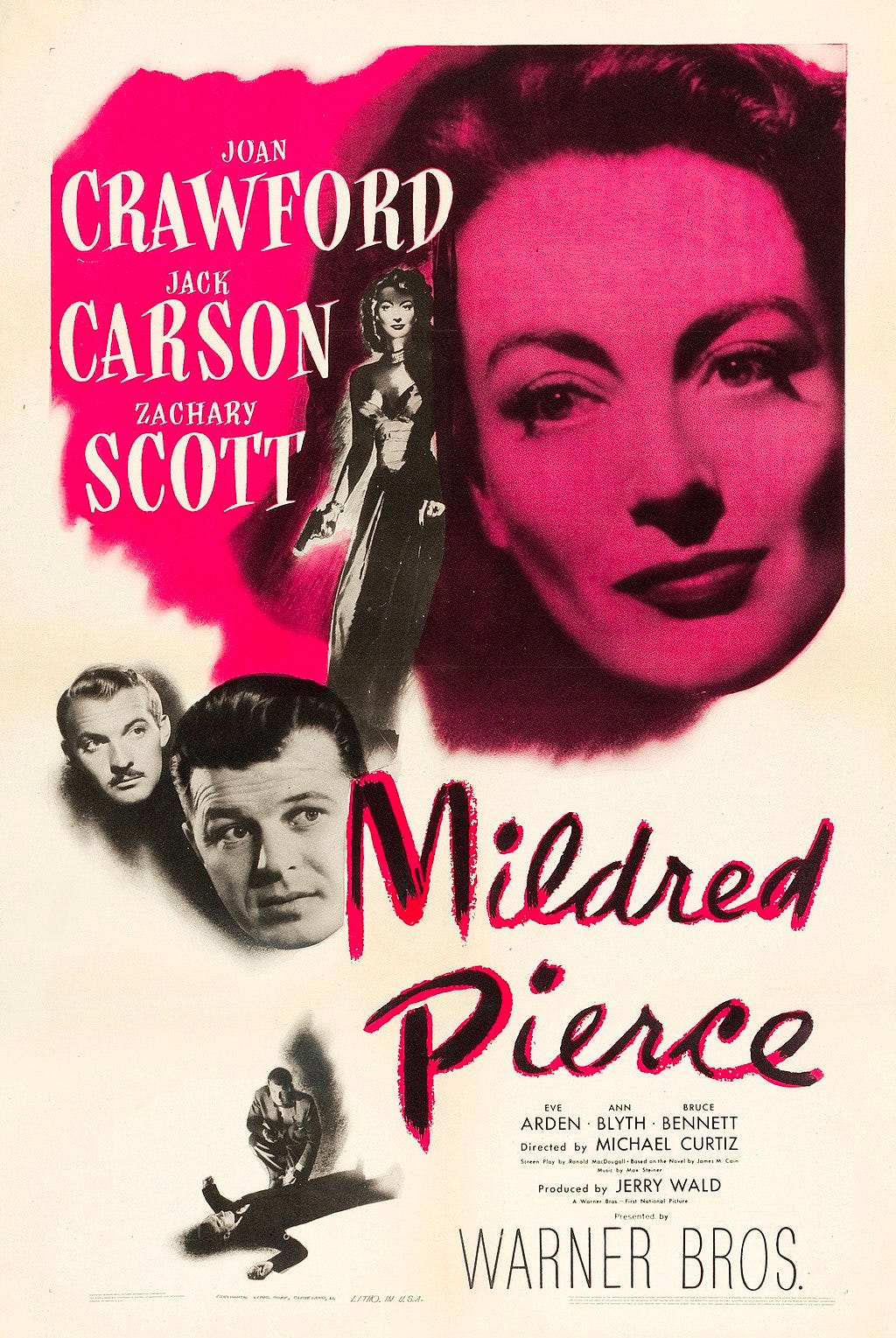

This is the fourth chapter in a long-simmering miniseries called “Narrative Architecture” about storytelling choices in fiction. There are many ways to tell a story, and in this series, I’ll examine the literary choices a particular author made and their impact on the story at hand. This week, I’ll engage with James M. Cain’s classic noir novel, Mildred Pierce (Knopf, 1941), the basis for the 1945 Joan Crawford film and the 2011 Kate Winslet HBO miniseries. Spoilers throughout—but this material has been around for a while. Just saying.

This post is a revised version of an essay I composed as part of my MFA program at UNR.

“In the spring of 1931, on a lawn in Glendale, California, a man was bracing trees” (Cain 219). So begins James M. Cain’s masterpiece, Mildred Pierce. Though the concept of “the Great American novel” is reductive, I would argue that James M. Cain’s Mildred Pierce belongs in the conversation—at least, in terms of the “Great California Novel.”

Set in Southern California during the Great Depression, Mildred Pierce tells the story of the eponymous woman who, against all odds, rises above her station but is destroyed in the process; her quick rise only leads to her even swifter fall. The impetus for both her rise and fall is her cardinal sin, pride. In Cain’s telling, nowhere else but California is the “American Dream” more romanticized and more false. Though California possesses the illusion of potential advancement, the vanity and betrayals inherent in its populace inevitably lead to the ruin of anyone who tries to move upwards. In Cain’s novel, pride is the fundamental error inherent to all Californians, a sin that does not go unpunished for long.

The opening scene of the novel asserts the theme of the novel as revolving around arrogance and misplaced pride. We meet Herbert Pierce, Mildred’s husband, gardening at his house, a subdivision he had been a partner in financing:

It was a tedious job, for he had first to prune dead twigs, then wrap canvas buffers around weak branches, then wind rope slings over the buffers and tie them to the trunks, to hold the weight of the avocadoes that would ripen in the fall. Yet, although it was a hot afternoon, he took his time about it, and was conscientiously thorough, and whistled. He was a smallish man, in his middle thirties, but in spite of the stains on his trousers, he wore them with an air. (Cain 219)

From the very first, Cain characterizes Herbert Pierce as putting on “airs” despite his modest existence. For Cain rather sardonically emphasizes that Herbert Pierce’s house, in the context of LA county, is not special at all:

It was a lawn like thousands of others in southern California: a patch of grass in which grew avocado, lemon, and mimosa trees, with circles of spaded earth around them. The house, too, was like others of its kind: a Spanish bungalow, with white walls and red-tile roof. Now, Spanish houses are a little outmoded, but at the time they were considered high-toned, and this one was as good as the next, and perhaps a little bit better. (Cain 219)

Despite Mr. Pierce’s pride, his house is barely distinguishable from the millions of others like it in LA. We soon learn that Pierce lost all his money in the stock market in 1929, and rather than stoop to get a job, he fell into an affair with Mrs. Biederhof, a slumlord who earns an income by collecting rent from Mexicans (Cain 226): “[Mrs. Biederhof] listened to tales of his grandeur, past and future, fed him, played cards with him, and smiled coyly when he unbuttoned her dress. He lived in a world of dreams, lolling by the river, watching the clouds go by” (Cain 226). Herbert Pierce cannot adapt after his fortunes changed, and rather than swallow his pride, he sinks lower into degradation, with a woman who profits on the backbreaking labor of California’s servant class of immigrants. Little does Mildred know yet, but she will share Herbert’s fate; Herbert’s life is a parable that foreordains Mildred’s destiny to “live in dreams.”

When Mildred finally becomes fed up with Herbert’s infidelities, she kicks him out of the house, but almost immediately realizes she needs to get a job to support her two daughters, Veda and Ray. But despite having no work experience, she at first balks at her first offer, to become a waitress. Her pride, and fear at disappointing the arrogant Veda (more on her in a minute) prevents her from taking this position. But the urgency returns, and she does end up taking a waitressing job, and in her pride pledges to make something more of her present situation—first by selling homemade pies, then by starting a restaurant. In these efforts she succeeds, and over the course of many schemes and opportunities negotiated by her allies, such as her shrewd neighbor Mrs. Gessler and the smarmy lawyer Wally Burgan, she even succeeds at starting a chain franchise of “Mildred Pierce” restaurants. Mildred’s rise, alongside her unexpected romance with Monty Beragon, a mysterious Pasadena heir, produces an exhilarating narrative thrill-ride for the book’s Depression-era reader. She lives the American dream Cain’s reader has often dreamt of. But Cain makes sure that the rise is always underscored by the idea that such prosperity is fleeting and always at risk due to his protagonist’s cardinal sin.

Across Cain’s work (such as The Postman Always Rings Twice, Double Indemnity), fate has a way of undermining his protagonists’ rise. In those earlier novels, men murder for money, and for love, and are punished for it. But Mildred’s crime, “if she had committed one,” as the conclusion of the novel tells it, “was that she loved [Veda] too well” (Cain 517).

This Achilles’ heel comes to the forefront in a pair of memorable scenes featuring the enigmatic Italian music teacher Mr. Treviso. In the first scene, Mildred takes Veda for an audition in front of Treviso to be accepted as one of the instructor’s pupils:

Mr. Treviso wandered over to the window, and stood looking down at the street. When Veda got to the slow part, he half turned around, as though to say something, then didn’t. All during the slow part he stared down the street. When Veda crashed into the fast part again, he walked over and closed the piano, elaborately giving Veda time to get her hands out of the way. In the bellowing silence that followed, he went to the far corner of the studio and sat down, a ghastly smile on his face, as though he had been prepared for burial by an undertaker who specialized in pleasant expressions.” (Cain 432-433)

Mr. Treviso, characterized as a gothic character, serves as a warning to Mildred. Veda’s pride (and amateur skill at the piano) are crushed when he rather brutally shuts the piano keys over her hands, a rather startling gesture. Serving as sort of an undertaker, he exists in this scene to convey to Veda her mediocre musical grave, self-awareness being the only aspect the Pierce family cannot attain.

In a rather old-fashioned and modernly problematic way, Cain uses Treviso as a dispenser of Old World wisdom. In the second scene with Treviso, after Mildred later discovers that Treviso has bafflingly taken on Veda as a student, not in piano but as a singer, he rather baldly points out Veda’s status in this noir as the femme fatale:

“You go to a zoo, hey? See little snake? Is come from India, is all red, yellow, black, ver’ pretty little snake. You take ‘ome, hey? Make little pet, like puppy dog? No—you got more sense. I tell you, is same wit’ dees Veda. You buy ticket, you look at little snake, but you no take home. No.”

“Are you insinuating that my daughter is a snake?”

“No—is a coloratura soprano, is much worse. A little snake, love mamma, do what papa tells, but a coloratura soprano, love nobody but own goddamn self. Is son-bitch-bast’, worse than all a snake in a world.” (Cain 467-468).

Treviso’s rather ridiculous comparison between Veda and a “pretty little snake from India” is hilarious, and elicits my favorite line in the exchange—“Are you insinuating my daughter is a snake?” But Treviso brings home the theme of the book when he says Veda’s gravest sin is that “she loves nobody but her own goddamn self” (Cain 468). Cain is subtle with theme in scenes like the description of Herbert gardening, but when he goes direct with the theme, he gets away with it. This I find astonishing, and these little operatic masterstrokes emphasize his talent at playing the reader like an instrument—knowing precisely when to push the theme button and for purposes that serve the novel as a whole.

He also doesn’t waste an amazing moment such as this one, and rather instead milks it for all it’s worth. After this speech, Mildred then rejoins that Veda is “a wonderful girl.” But Treviso replies: “No—is a wonderful singer”:

As she looked at him, hurt and puzzled, Mr. Treviso stepped nearer, to make his meaning clear. “Da girl is lousy. She is a bitch. Da singer—is not.” (Cain 470)

Mildred’s willfull blindness to Veda’s negative qualities are amply demonstrated in this exchange. In the novel, Veda represents the culmination of both Herbert and Mildred’s pride. Though she is talented, her pride makes her a snake. Mildred’s pride of Veda is therefore her downfall. Her need to have Veda in her life causes her to ill-advisedly marry the shameless Monty Beragon and buy his aging Pasadena mansion, a plan which works to bring Veda back into her orbit for a time, until the vagaries of such an outsized step overwhelm Mildred’s finances. As Cain describes (rather dryly) in the moment that Veda performs in the Hollywood Bowl with Mildred in the audience:

This was the climax of Mildred’s life…. It was also the climax, or would have been if she hadn’t gotten it postponed, of a financial catastrophe that had been piling up on her since the night she so blithely agreed to take the house off Mrs. Beragon’s hands for $30,000…. (Cain 497)

Mildred’s financial collapse is described like that of a tabloid columnist, one sarcastically written in telling of someone being served their comeuppance. The coup-de-grace comes when Mildred discovers Monty and Veda in bed together. In scandal she loses her daughter, her husband, and her business; ironically losing the ability to conduct business “under her own name,” a further hit to the pride and the ego of “Mildred Pierce,” adding another level of meaning to the book’s title as it represents the rise and fall of the ‘idea’ of Mildred Pierce the person, and also the myth of the business she started (Cain 513).

In the concluding pages, Herbert joins Mildred in Reno as she waits out a divorce from Monty. Both Mildred and Herbert have lost fortunes which proudly declared their own names as founders and proprietors. Both of them have succumbed to the ills of pride by believing that they were better than everyone else, by advancing too fast too quickly, by nurturing a venomous daughter who was never taught to live with less. In the final line, the former couple, now reunited in mediocrity and ruin, commit to getting drunk: “Let’s get stinko” (Cain 517).

Written in the Great Depression, reflecting a time when many Americans faced financial ruin after a decade of unprecedented prosperity, Mildred Pierce showcases a reckoning with American mediocrity, that a nation steeped in ideals of freedom and rugged individualism is doomed to produce tragic characters like Mildred, who almost succeed at making better lives, and then don’t. Mildred Pierce is ever more resonant today as our nation recovers from the rule a narcissist on par with Veda and a series of economic catastrophes which further undermine our country’s tradition of misplaced exceptionalism.

Mildred’s pride makes her both capable of rising to the moment—and dooms her to giving in to her worst impulses. The weakness is a strength, to a point. That’s why Mildred Pierce is brilliant, and deserves far more recognition in American letters.

References

Cain, James M. The Postman Always Rings Twice, Double Indemnity, Mildred Pierce and Selected Stories (Everyman’s Library (Knopf): New York, 2003).