The Black Utopians

Aaron Robertson on the historical foundations of Black countercultural spaces

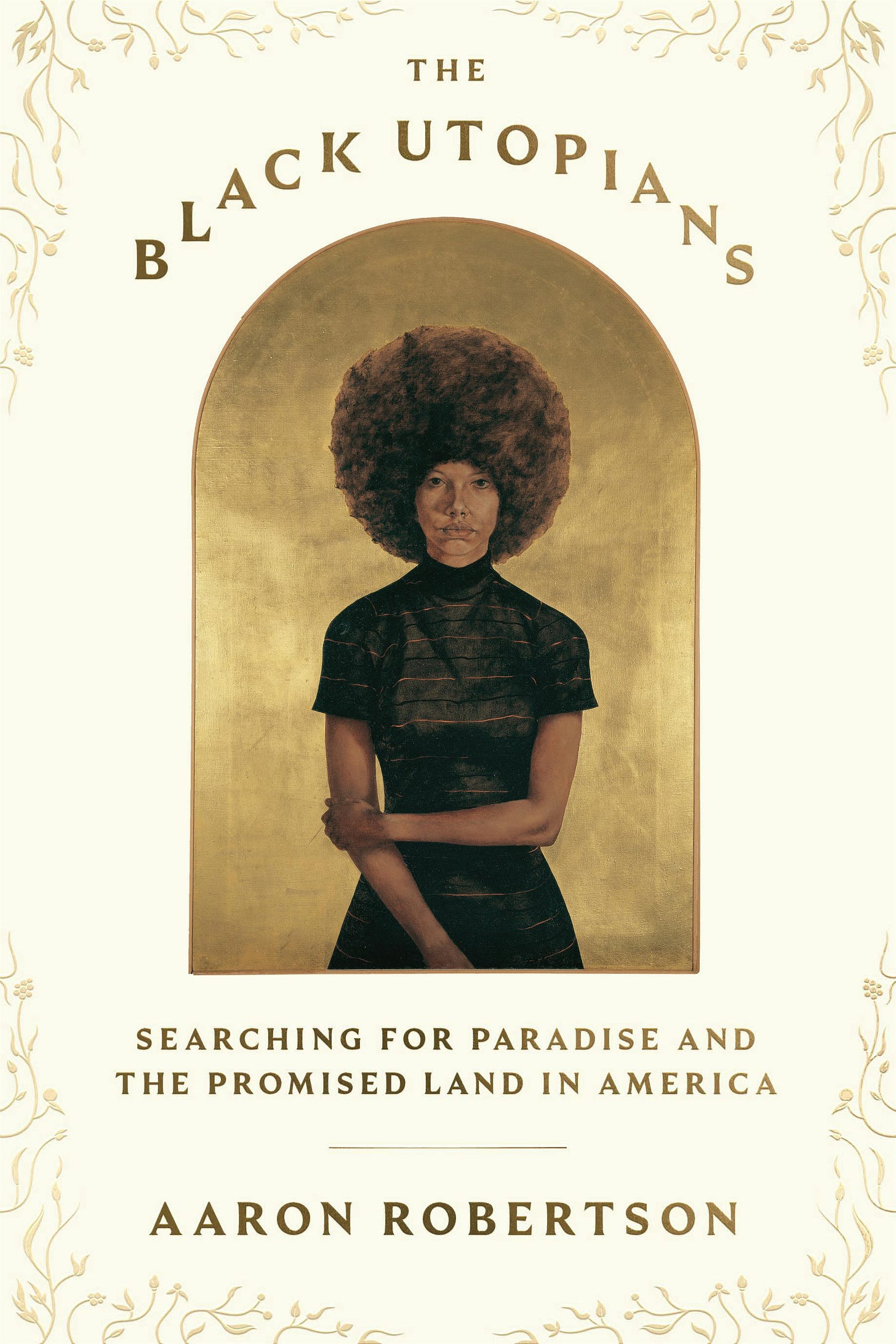

In each installment of “The Usonian Interviews,” The Usonian spotlights a storyteller from a different corner of the globe. This week, The Usonian spoke with author Aaron Robertson about his book The Black Utopians: Searching for Paradise and the Promised Land in America (FSG, 2024), which explores the roots and growth of countercultural Black movements in the 1960s. I previously spoke with Aaron in 2021 when this Substack was just getting started, so I’m thrilled to have him back on the blog to talk about his phenomenal new book. You can order The Black Utopians from Bookshop, Barnes & Noble, or Amazon.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length. The views presented by the interview subject are the opinions of the subject and do not represent the views of the article’s author or this newsletter. Browse the full interview archive here.

THE USONIAN: The book follows several figures who worked to create their own visions of Black Utopia, all revolving around the Shrine of the Black Madonna, a church in Detroit. These figures included the controversial preacher Albert Cleage Jr. and the artist Glanton Dowdell. For our readers, can you tell me about the basic history of the Shrine of the Black Madonna and what drew you to this topic?

AARON ROBERTSON: The Shrine of the Black Madonna is best known as a Black nationalist institution that has its roots in the 1950s. The church used to be called the Central United Church of Christ. It’s a Protestant church established by Albert Cleage Jr., who was the scion of a well-to-do African American family in Detroit. In the early 1960s, Cleage starts to move away from the “civil rights consensus,” so to speak, for various reasons, and begins to really embrace what we now know as the Black Power movement and Black nationalism. By the late 1960s, the Shrine of the Black Madonna became a pretty well-known institution within the Black Freedom Movement. The church was elevated after the 1967 Rebellion in Detroit, because Reverend Cleage, who was this outspoken activist within the city, became the public face of Black nationalism in Detroit.

He not only preaches Black Power, but he also advocates for the creation of Black-owned businesses. He starts calling for the creation of Black cooperatives, even all-Black communes and neighborhoods. He’s best known for his radical re-envisioning of Christianity itself. You know, he’s one of the forefathers of what is known as Black Liberation Theology, which is essentially this notion that God is a God of the oppressed, and God’s sympathies lie with those who have been dispossessed and disinherited. In the late 1960s, these beliefs were connected to a lot of young African Americans who were looking for a spiritual home.

Many roads lead to Rome (or Detroit, in this case). But I was doing research for a fiction project, for a novel that I wanted to write. It’s also set in Detroit and about the intersection of the Black Power period [with the Second Vatican Council], when the Catholic Church was really transforming.

I was interested in that story, but I read this memoir by a Black priest named Lawrence Lucas, who was based in Harlem, and in his book, he mentioned the name of a pastor in Detroit who he found inspiring—Albert Cleage Jr.—as well as the name of the Shrine of the Black Madonna.

I grew up going to many different kinds of churches within and outside of Detroit. But I’d never heard of Cleage and the Shrine. That took me down a rabbit hole. And then I learned a little more about some of the projects that the church had spearheaded, namely one called Mtoto House, which was a children’s commune that took its main inspiration from the kibbutz in Israel.

I was like, what was going on here? I knew that the church had gained its reputation during this moment of great countercultural fervor. And I had long been interested in countercultural movements and this idea of utopia. So I wanted to understand what the roots of Black countercultural movements in Detroit were. Over time, that question expanded into the historical foundations of Black countercultural spaces.

There was some point in college that this random question popped in my head: Were there Black hippies? I must have been thinking of Jimi Hendrix, and I knew a little bit about Sun Ra and eventually learned about Alice Coltrane.

But apart from these very prominent public figures who you could associate with the New Age, I didn’t know where the Black hippies were. That pulled me into the story of the Shrine. It starts off as this very explicitly Black nationalist church. And then the church kind of drops off the map. The height of its fame is the late 1960s, but by the early 1970s, many people start to forget about the church, and the church becomes more focused on its internal development and projects.

In the mid-1970s, Cleage adopts this philosophy called KUA, “the science of becoming what you already are,” drawing from the teachings of Eastern mystics. He’s also inspired by quantum physics. So this Black nationalist church slowly transforms into a New Age church, a Pan-African New Age church. This one institution became a great way to illustrate the development of American countercultural thought.

TU: Glanton Dowdell, an influential artist who designed the mural of the Black Madonna for the Shrine, is an incredible historical figure. Like there’s something out of a great Dostoevsky novel—or Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man—about his journey as a vagabond-turned-artist, and then an exile in Sweden. And you tracked down his descendants, some of them in Sweden. Tell me about how you uncovered this figure who has been overlooked in many ways and what that journey was like?

AR: A lot of Americans think of Scandinavia as this sort of utopian space. For Bernie Sanders, there’s nothing the Scandinavians haven't figured out, with their health care and their support of labor movements. Especially when Sanders was in the spotlight, people on the left were talking about Scandinavia a lot. What country might be associated with a real sense of what utopia can actually look like in the world? And people will point to Sweden.

Glanton Dowdell was a Black nationalist painter who also spent a lot of time in prison and then self-exiled, of all places, to Sweden during the Vietnam War. Sweden’s stance on the Vietnam War was an important part of that period, and so I wanted to understand the story of this Black revolutionary artist who lived for much of his life in the paradigmatic European utopia. What got him there? What aspects of his own life outside of Sweden could we understand as utopian?

When I conceived of the book, it was going to be organized more thematically. One of the themes I kept returning to was that of Black fugitivity, of the Black fugitive as a kind of utopian. There’s something about the archetype of the Black fugitive that resists capture. It’s hard to pin them down because they’re constantly moving and transforming. The same can be said of utopia. There’s a relationship between a fugitive who’s always on the move and a utopian who can’t really be static.

TU: One of the wonders of this book is how you take familiar incidents from history—the March on Washington, the 1967 Detroit Rebellion, but casting them in a new light and turning them on their head. By foregrounding Cleage’s role, and Dowdell’s, we see these events from a totally new vantage. How did you approach writing about these big moments in history and how to reframe them?

AR: I am daunted by subjects that many people have approached before. Even thinking of my work as a translator, I’m always so amazed by the people who are like, I’m gonna translate Dante—like, I’m going to do it again. It’s courageous and bold (or maybe hubristic) [to think] that you can say something new about it.

I knew that I had to write about the Civil Rights Movement and the Black Power movement. I am not a trained historian, first of all, so I didn’t want to rehash narratives that many of us are familiar with—that would have bored me. I tried to find ways to get into the experience of people who aren’t well-known in general, and to understand how they interpreted what is now history, but then was the present. The thing that helped me the most with that, or that helped me take these fresh perspectives on that period, was by speaking to the people who were a part of these movements, many of which were subterranean.

TU: Most of the story is very aligned and sympathetic with Cleage’s project. But at a certain point you push back a little bit, and examine whether the Shrine of the Black Madonna was a cult. And there were some linkages to Jim Jones, who drew inspiration from some of the Black Utopians for his own nefarious ends. A binary evaluation, of course, is limiting, and I think many people forget that in our polarized age. How do we evaluate groups like Cleage’s when they might share similarities to groups that had much more dangerous outcomes?

AR: A lot of people who know about Jonestown are aware of the awful mass murder. But I hadn’t known that the People’s Temple was majority-Black. That wasn’t really emphasized so much in stories about Jim Jones. Not only that, it was a revolutionary socialist church. At least initially, it was framed as this utopian community, which was fascinating to me. It was important in the book to [acknowledge] that Utopia can take a bad turn.

I come out in the book largely as sympathetic to the possibilities of the idea of utopia, but I didn't want to write something that painted Black utopianism as this unquestionably uncomplicated and good thing. I don’t think the Shrine of the Black Madonna was a cult in the way that we think of the Peoples Temple, but some of the people I spoke to who support the church were pretty even-handed. There are parts of communal movements that can be harmful. It’s the struggle between individualism and communalism. There’s beauty to both, and there are also real risks.

TU: There are all these unconventional connections. Like Black communities that grew after the Civil War and learned German. The presence of Black anti-war and activist exiles in Sweden. The kibbutz model being an influence on some Black utopian thought. Also, the Essenes civilization that produced the Dead Sea Scrolls providing a model for a self-sustaining community enclave within a larger society. And even the USDA’s discrimination against Black farmers, which seems like something that should be a bigger deal. How do you contend with all these provocative connections, and what do you make of them?

AR: At the root of utopianism is an anti-establishment attitude. There is something about the way that the majority of our society is structured, that to utopians or utopian groups, it’s not working for them—whether that’s something about the economy, how our politics are organized, or whether it's how we come together as spiritual communities—that the mainstream way of living our lives is unacceptable.

And so, in writing about groups like the Essenes, like the kibbutzniks, people who have read scholarship about Utopia will see these groups mentioned all the time. The Essenes come up repeatedly because it was one of the early examples of a communal movement, this ancient Jewish sect that didn’t like how things were being done in the [Second Temple]. They thought that religious leaders were corrupt and wanted to separate themselves from that. I may not say this so explicitly in the book, but I really believe that the Shrine of the Black Madonna as an institution is the most explicitly Black utopian institution of the 20th century. That’s why I wanted to make sure I threaded these other examples into the story.

TU: The book features many paintings in the text. Can you tell me about those?

AR: Those are painted by Glanton Dowdell’s daughter, Stacy McIntyre. When I learned that she was an artist, I wanted her work to be a part of the book so that she could create a visual link between the personal stories, the personal aspect of the book, and the historical stuff. I wanted her to paint the Promise Land schoolhouse. And I wanted that style to also tie together her painting of her dad's mural—I wanted her to paint the Black Madonna.

TU: The book features a narrative spine about your father, who was in prison, and your difficult relationship with him. You have these letters your father wrote to you, but you also write to say you had to ask for him to reconstruct these letters. And your father is clearly an incredible writer. Could you explain how you used this device as a spine which spans the entire book?

AR: My dad was incarcerated from when I was eight to 18. During the time of his imprisonment, particularly when I was younger, we would often exchange letters and because he was in Michigan, and my grandparents (his parents), still lived in Detroit, we would occasionally drive two hours to see him. In the earlier years, we exchanged letters more frequently. But as time went on, as I grew up and life went on for me, I grew more distant—not apathetic, just more distant. Because we hadn’t lived those first eight years of my life together, he was almost like someone I was getting to know, mostly through these occasional visits and letters.

At some point along the way, I lost the letters, which I think was somehow symbolic of where our relationship was. When he got out, he was trying to make up for so much lost time, not only with me, but with so many people in the family. And there were parts of that that made it hard for us to really get emotionally close. He’s a real dreamer and an amazing storyteller, because he had written this one short story to me when he was in prison. I was young, and I read the story, and I had no idea that he was a writer.

In 2020, I wanted him to write about his life. I wanted him to write about the life that he had envisioned for himself, the life that actually ended up happening, his hopes, and what he hoped for after his release. I think the reason I’m interested in utopia as an idea is because, for me, utopia is always about alternatives.

Aaron Robertson is a writer and literary translator from Italian. His debut book, The Black Utopians: Searching for Paradise and the Promised Land in America, was selected as a New York Times Notable Book of 2024, a Washington Post Best Nonfiction Book of 2024, one of TIME’s 100 Must-Read Books of 2024, and one of the New York Public Library’s 10 Best Books of 2024. It was also recognized as a best book of the year by The New Yorker, The Boston Globe, The New Republic, ELLE, Essence, Literary Hub, and the Chicago Public Library. His translation of Igiaba Scego’s Beyond Babylon was shortlisted for the 2020 PEN Translation Prize and the National Translation Award, among others, and in 2021, he received a National Endowment for the Arts grant in translation. Aaron previously served on the board of the American Literary Translators Association and is currently an advisory editor for The Paris Review. His work has appeared in various outlets, including The New York Times, The Nation, Foreign Policy, and more.

Loved chatting again, Harrison!