Southwestern fantasy

The imaginative, globalized regional architectural heritage of the Southwest

It wasn’t long after I arrived in Cyprus that I stumbled on an uncanny image that made me feel a strange fit of déjà vu. In the northern part of old Nicosia, within what is known as the unrecognized state of “The Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus,” are several historic monuments that have been re-tooled for tourism purposes.

One of these is Büyük Han, an inn dating back to the Ottoman Empire—sort of like the medieval version of a motel. In what had been the former bedrooms and stables of this establishment are artisans who sell trinkets and other souvenirs to tourists. And some of these products were very surprising—far from the typical wares typically found in Mediterranean locales.

That’s because some of the items sold were associated with a completely different culture. Turkish Cypriots were selling dreamcatchers.

The dreamcatcher is typically associated with Native American art. Though they originate from the Great Lakes and became a popular symbol with the rise of the American Indian Movement in the 1970s, they tend to be associated with the peoples of the Southwest.

And here, in the middle of Cyprus, were what seemed to be unmistakably dreamcatchers with some local symbols and innovations. The above photo shows dreamcatchers with the Mediterranean evil eye motif and the traditional lefkara lace of Cyprus.

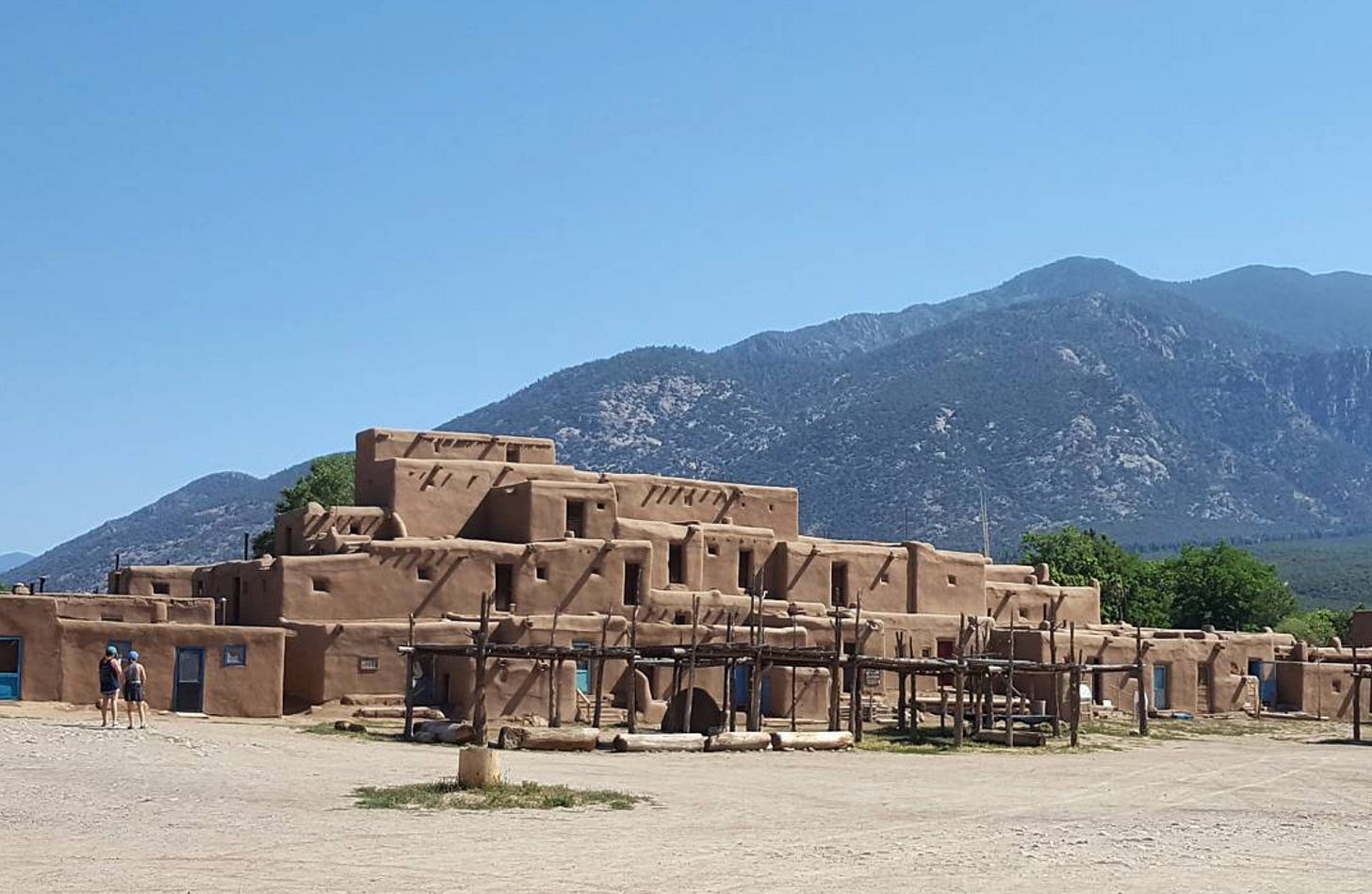

The episode got me thinking about the global influence of a regional mythology as expressed through art and architecture. After I spent a summer reporting at The Taos News in Northern New Mexico, I had become interested in the motif of Pueblo Revival architecture—an attempt to reinforce a vernacular building style to define a region. The Southwestern U.S. was the center of many indigenous cultures that were conquered and absorbed into the Spanish Empire, eventually becoming the territory of New Mexico. All of this building style is rooted in indigenous dwellings, such as the historic Taos Pueblo, the oldest continuously inhabited structure in the United States, perhaps existing as such for a thousand years.

Even though places like Taos and Santa Fe are renowned for this local building style, the effect is more calculated, and much more recent than Taos Pueblo. In fact, many of the buildings in this style date back to the 1920s. And many were designed by a single figure—the Brazilian-born, American architect John Gaw Meem (1894-1983).

In places like Taos Plaza, souvenir shops hawk turquoise, silver, and dreamcatchers—just like in Cyprus’ Büyük Han. What places like Taos Plaza sell is a “fantasy” of the Southwest—one that evokes the Wild West, even though the architectural style in the region during the 19th century was more colonial in style, featuring neoclassical columns.

In fact, the movement to give the Southwest a regional identity stems from the City Beautiful movement in the early 20th century and tourism-centric marketing by the Santa Fe Railroad. In fact, John Gaw Meem, the architect responsible for many Pueblo Revival buildings in New Mexico, was first inspired to move to the state thanks to the Santa Fe Railroad’s marketing of the region in New York City. Similar processes occurred in Southern California, where architects like Bertram Goodhue tried to give the region a Mission Revival-look to advertise the region’s historic heritage as Alta California, the Andalusian fantasy of a New Spain.

The process of establishing the Southwest’s regional identity began as early as the first encounters between the Spanish invaders and indigenous tribes, when a Southwestern fantasy advertising a “city of gold” of rich heritage and history was promulgated—either to attract or repel its visitors.

I explore this history in depth in my essay, “Southwestern Fantasy: Pueblo Revival in New Mexico” in the latest volume of Architectural Humanities Research Association’s Critiques series: Region from Routledge. The essay is based on my presentation at the AHRA conference in 2021. I’m very proud to contribute this text to this edited collection. The volume features many fascinating essays on the subject (including a few more on Cyprus). You can order a copy from the Routledge website here or a major online retailer.

As the dreamcatchers in Cyprus elide, the legacy of the Southwestern fantasy is global. Even if a motif is calculated (and consciously artificial), it doesn’t mean that the effort is not desirable. But it’s the process of an artificial design aging into a status of cultural authenticity and heritage that interests me. What is authentic? Can anything ever be?

Many thanks to Professor Simon Richards of Loughborough University for encouraging me to attend the conference and develop the essay for the Routledge volume, which he co-edited.

This is the thirty-fifth post in The Cyprus Files, a newsletter series from The Usonian chronicling my Fulbright experiences in Cyprus. Thanks for reading, and if you haven’t subscribed to The Usonian to learn about storytelling and design from the edge, please consider joining the list.

The Usonian Appendix

News & updates from the Usonian world

We have a new web domain. If you type in “www.theusonian.com” into your browser, you’ll be directed to the site. Plus, the old domain (“www.harrisonblackman.substack.com”) still works. Imagine that—an upgrade, without broken links!

Coming up: Carhenge. Yep, that’s right—Carhenge. Stonehenge made of cars!

Also: An interview with Casey Bell on her short story collection Little Fury.

Plus: A big announcement about the future of The Usonian (hint: it’s good news).