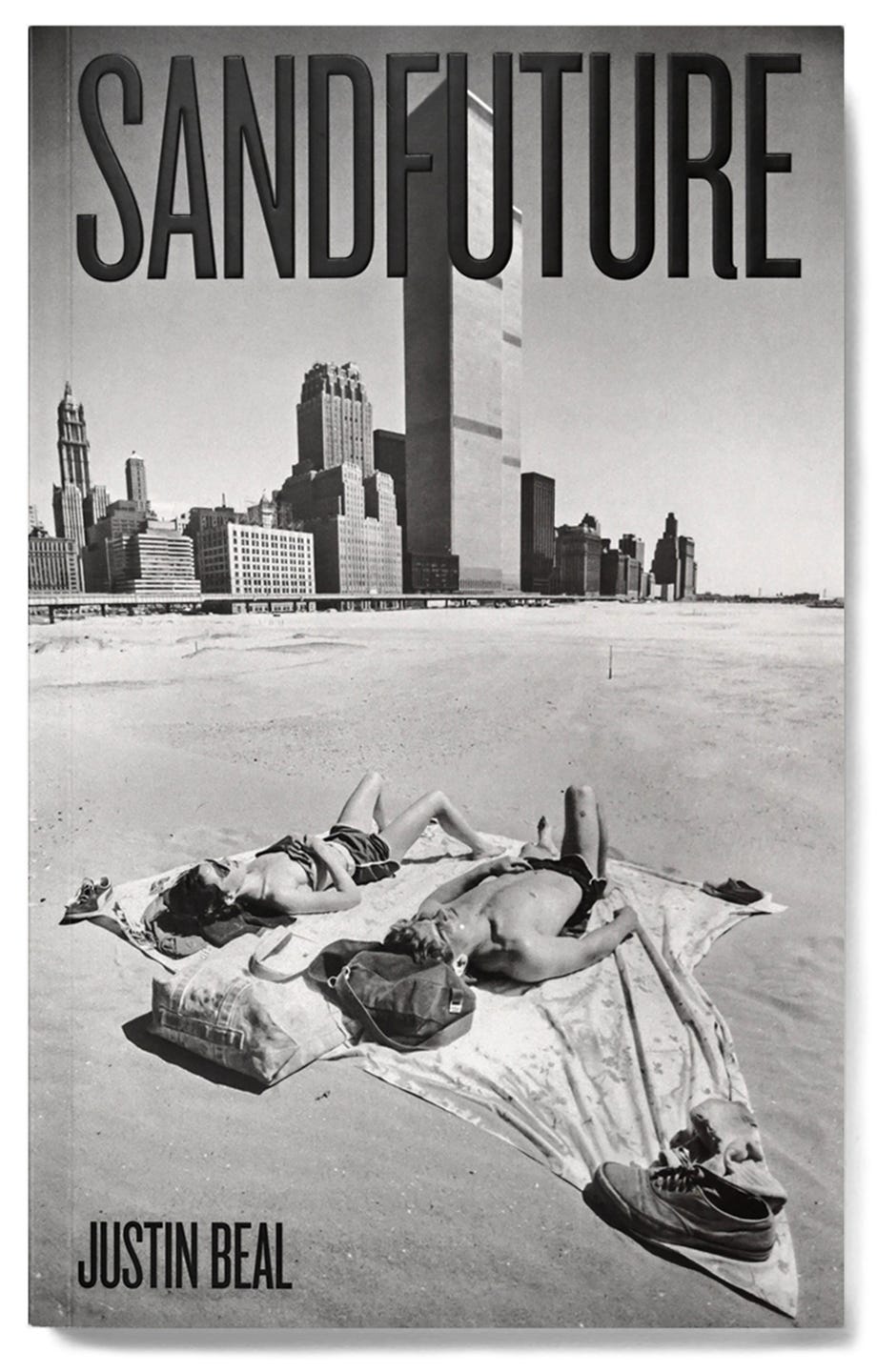

In each installment of “The Usonian Interviews,” The Usonian spotlights a storyteller from a different corner of the globe. This week, The Usonian spoke with artist and writer Justin Beal about Sandfuture (MIT Press, 2021). In addition to being an innovative biography of Minoru Yamasaki, the Japanese American architect of the World Trade Center, the book doubles as a lens into Beal’s personal experience of modern architecture. You can order Sandfuture from MIT Press, Bookshop, or Amazon.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length. The views presented by the interview subject are the opinions of the subject and do not represent the views of the article’s author or this newsletter. Browse the full interview archive here.

THE USONIAN: What drew you to the story of Minoru Yamasaki, architect of the original World Trade Center?

JUSTIN BEAL: After I graduated from college in 2001, I moved to an apartment with four other people in Lower Manhattan, two blocks south of the World Trade Center. I was fascinated by these two buildings and perplexed by the fact that I had just graduated with a degree in architecture, but I had no idea who designed [the Twin Towers]—at the time, they were still the second and third tallest buildings in the world.

So I looked into whom the architect had been [and when I realized it was Minoru Yamasaki], I connected him back to a number of other projects that were significant. Pruitt-Igoe was an obvious example, but there was also the Eastern Airlines Terminal at Logan Airport, or the Century Plaza Towers in Los Angeles. So I had long been conscious of Yamasaki as a marginalized figure.

Then 9/11 happened, and I moved out of that neighborhood. I went on to do other things, mostly making art. But when I came back to this idea of writing twenty years later, Yamasaki was still at the front of my mind as somebody I wanted to learn more about.

TU: It’s a difficult balance to write a book that functions as a biography of one person that also functions as a personal memoir. Sometimes books like that can feel a bit unwieldy. I’m thinking of Paul Hendrickson’s Plagued By Fire, about Frank Lloyd Wright, which is a brilliant book, but the author puts himself in the story in a way that is sometimes distracting.

But in Sandfuture, I thought you pulled it off. Your memoir complements Yamasaki in a way that was additive and effective. How did you come to this structure? What was it about Yamasaki’s life that you felt you could so deeply and profoundly relate your own experiences to his story?

JB: I think [the Hendrickson book] is interesting in a different way, because it’s retelling a story that’s been told many times. The fact that [the Frank Lloyd Wright fire story] exists in so many other tellings gives Hendrickson license to really push some boundaries. There are moments in that book that I find scintillating, and other moments where I’m like—wait, hold on! It is an interesting precedent for sure.

I’m aware of the ways in which the choice to juxtapose these stories from my life with the stories of Yamasaki’s life is absurd on many levels. It was never my intention to compare any of my accomplishments or failures, unspectacular as they have been, to the life of this person who was one of the most prolific and influential architects in American history.

For a long time, the fear of that appearance really restrained me from writing the book in the way that I ultimately wrote it. My intention was to write about architecture in a more personal way. And to somehow translate my own experience of architecture, which is very personal and time-based. It isn’t about an object, it’s about an interaction you have with an object, the time you spend with something, the actual feeling of being inside a building.

I was thinking about how so much of the writing that I’ve read about architecture fails to address that personal dimension. Your perception of a building can depend entirely on your mood, the weather, who you’re with, and what happened that day. I was trying to figure out how to write about architecture in a way that was more embodied, more personal.

For example, everyone always photographs architecture with no people in it—which is insane. And to a remarkable degree, people often write about architecture with no people in it. Buildings become interesting once they’re populated. So you have to inhabit them in the writing.

The incident that allowed me to push the myself further in that direction came when I was in the process of writing the book. I really had the sense that I was onto something, writing about this architect that no one had written about in English for 40 years. I felt the excitement of doing some very urgent historical work, coupled with the anxiety of not really being a historian. Then, somebody brought to my attention the fact that somebody else was also doing a Yamasaki book, and that became Minoru Yamasaki: Humanist Architecture for a Modernist World by Dale Allen Gyure, who has since become a friend.

When I received news of Dale’s book, I thought my project was redundant. But after a couple of days of feeling bad for myself, I realized that because he had taken over the responsibility of rendering Yamasaki’s career in its full complexity, that liberated me to do something much more experimental. I no longer felt the burden of representing everything Yamasaki did and no longer felt like I needed to figure out how to deal with all the drawings and images. I could put more energy into crafting a story that was not totally comprehensive, but more personal in the way that I wanted it to be. Again, not because I was trying to compare myself to Yamasaki, but because the book is about both Yamasaki’s role in history, and also how it looks from my vantage point. To look at it through a personal lens.

TU: Yamasaki’s Pruitt-Igoe project was one of the most notorious examples of failed public housing. How did Yamasaki’s original intent become tarnished when the building design was compromised? How did intent depart from the outcome?

JB: The story of Pruitt-Igoe is the entire history of America in a single project. It goes back to Lewis and Clark, Western expansion and our attitude and how we feel entitled to be on this land that we live in. It’s an incredibly complicated story.

On the one hand, it’s a story about the Housing Act of 1949, and the desire to build public housing in the United States; on the other hand, it’s also a story about the history of St. Louis. You cannot just take a model of public housing imagined and tested in a city with the density of New York City, and move it to cities like Chicago and Minneapolis, which are fundamentally different urban environments. And St. Louis is even more specific in a number of ways that have to do with the structure of the city within the county, but also have to do with the specific time and place.

For example, Pruitt-Igoe was conceived at a time when the population of St. Louis was forecasted to grow and grow. But, in fact it shrunk and shrunk, and is continuing to shrink. Pruitt-Igoe was also built at a time when a lot of larger systems were being put in place. The construction of freeways facilitated white flight, and the sequestration of the Black community within the urban limits and segregation laws that changed the fundamental make-up of Pruitt-Igoe, which was originally intended to be two different projects—a “white” housing in Igoe, and African American housing in Pruitt.

So all these things conspired to create a problem that no architect could have successfully solved. Yamasaki’s intention was originally to use much lower-rise buildings more suited to the vernacular of St. Louis—more like townhomes with some large towers. Those got value-engineered-out. If you look at the government requirements of public housing in the Housing Act, they’re so strict that there was very little any architect could do.

There are many elements of that design intended to be generous to the occupants, the most obvious example being the floors within the building that had services like laundry, playrooms, and elevators, but ultimately these floors ended up becoming some of the most dangerous and dysfunctional spaces in the building.

For reasons that were totally outside of the architect’s control, the buildings were never fully occupied. And the model for public housing required full occupancy to sustain maintenance. So once that model started to collapse, there wasn’t enough occupancy to sustain the maintenance of buildings, and things started to deteriorate. It was a perfect storm that had to do with reasons as vast as the patterns of the Great Migration during the Industrial Revolution and the suburbanization of the United States following World War II.

One of the criticisms often made of public housing in that era was that these projects were designed and built by entitled white men who didn’t understand the conditions of the lives of the people for whom they were designing—but Yamasaki actually understood the conditions of the people for whom he was designing perfectly. However, given the parameters of the project, he was still unable to meet those needs.

TU: In one of my favorite passages from the book, you refer to Paul Virilio’s “concept of the integral accident: the notion that every new technology contains within itself the germ of its own destruction.” ‘When you invent the ship,’ Virilio writes, ‘you also invent the shipwreck; when you invent the plane you also invent the plane crash.’… The technology of the skyscraper cannot be decoupled from the specter of its own failures.” (193) Your book considers your personal experience of New York’s recent disasters, from 9/11 to Hurricane Sandy. Could you expand on the ambiguity of novel technology, the opening of possibilities both positive and catastrophic?

JB: The metaphor of the ship and the shipwreck is one that I think about all the time. There’s this late capitalist faith, that no matter what predicament we get ourselves into, we can solve our way out of it with technology. Time and again, the way that story is told to us is through this idea of technology with all upside and no downside.

Take, for example, Tesla. It’s complicated to think about electric power as “good.” Buying a Tesla does not encourage you to moderate your consumption or drive less. It allows you to drive even more, but you’re using this other technology, and there’s this idea that this technology is free and unburdened of consequence. But now, there are other minerals that need to be extracted to make these batteries. Then there are all these complicated questions about where the power is coming from that is powering those cars. If you’re driving a Tesla in Los Angeles, and California is buying energy from Arizona, and Arizona is burning coal, where does that leave you? There’s a tendency not to think about the other side of that technology.

The architectural theorist Keller Easterling has this idea of “the multiplier”—an elevator, for example, is a piece of technological software that you input into the computer that is architecture. Once you import this technology, suddenly you can go up higher, and everything changes, everything multiplies. But of course, there are consequences of having taller buildings.

Air conditioning is another example of a multiplier. Once you have air conditioning, you can expand out and have a lot of people living in places that don’t make sense for people to live. They can live there because of this technology. But what are the consequences of putting millions of people in a place that has no water, like Phoenix? There’s a tendency to always see technology as a step forward. The power of the Virilio idea is just that with each of those steps forward, there’s a new high, but there’s also a new low.

TU: Pretty much everyone who takes architecture or urban studies classes in the US comes across the Vincent Scully [not the Dodgers announcer] books or the narrative he propounded about American architecture. As you write in Sandfuture: “Like any academic canon, Scully’s chronology tells a story, but it is also just a story and one that, favoring cohesiveness over completeness, puts undue emphasis on certain accomplishments while omitting others entirely” (67). Yamasaki was left out of this narrative. What are the other moments or figures you think we should not omit in the instruction of the history of American architecture?

JB: I’ve been writing about John C. Portman Jr. (1924-2017), who was completely marginalized by the architectural community because he embraced this very logical idea of wanting to control his architectural projects. He became an architect and a developer and the academic-architecture profession made him into a pariah because it couldn’t handle the collapse of two things typically held in “productive opposition.”

Paul Revere Williams (1894-1980) had an incredible influence on the vernacular architecture of Los Angeles. His story is especially important because of the lack of diversity in architectural history, though he’s a good enough architect in his own right to be relevant for reasons that have nothing to do with race; the same is true of Yamasaki.

Wallace Harrison (1895-1981) had more of an impact of what New York City looks like than anyone other than Robert Moses and yet he’s a figure that most people never think about. Shining a light on all those different figures is interesting because it complicates the narrative. There are many more.

What’s so compelling about Scully is that he’s an archetypal example of how patriarchal academic history works. His way of telling the history of American architecture is incredibly seductive. As a young student taking his class, it was one of the things that brought me into the field. Scully simultaneously represents how powerful a well-told story can be and shows how much is often omitted to tell the story in a compelling way. You have to omit a lot of things and the consequences are what’s left on the cutting room floor. I’ve been aware of the ways in which I’ve had to “unlearn” that history in order to expand my own consciousness in exactly the same way that I’ve had to “unlearn” histories of art.

Scully became important in the context of this book, because he so explicitly cut Yamasaki out of the story. Recently I was talking to somebody several years younger than myself, who was taking Scully’s class on the morning of 9/11. Scully was well-known for dismissing the World Trade Center as an abomination of late capitalist architecture, but this person explained how [on the morning of 9/11], Scully recognized instantly that his opinion of the building had to change. Suddenly, it meant something completely different. Scully was processing these events in front of 400 students and realizing, No, actually, I was wrong. The building now means something else. He was revising history on the fly.

So much of American academic architecture’s energy comes from this tiny group of people in Princeton, New Haven, and Cambridge. If somebody taught at one of those schools for 50 years, like Scully did, they influenced many of the people who are practitioners, writers, and critics. Scully’s reach was enormous.

TU: A major aspect of the book concerns your wife’s battle with persistent migraines, and how Sick Building Syndrome might be a contributing factor to illnesses experienced by many. How do you see the “sick building story” complicating the narrative of architectural history and "progress"?

JB: Sick Building Syndrome is where I first started the research for this book. I was interested in the ambiguity around Sick Building Syndrome. The term emerged at a moment in history when a confluence of occurrences, specifically the energy crisis that began in the US in 1973 and the subsequent need to conserve energy coincided with this flood of new materials into the construction industry in the wake of the Second World War. A lot of this technology had been developed for wartime applications and then became applicable to residential construction at a time when there was a huge construction boom. So you have all of these new, untested materials, and then this obsession with creating tight energy-efficient spaces, plus various other factors, which created conditions where buildings were in fact “sick”—it is both a metaphor and a description of exactly what is happening because both the building itself, and the people within it are sick.

Sick Building Syndrome was a real thing, but it was never really treated. It was always dismissed as a crackpot idea. People who were suffering were considered paranoid, but we can look at very specific things—there is formaldehyde in the glue that we use to make carpets, for example, and when you make a building hold all the energy in, there’s no natural ventilation that lets carpet off-gas, so it makes people sick.

Baked into the EPA definition of Sick Building Syndrome is this beautiful contradiction—as soon as you identify the cause of Sick Building Syndrome, it’s no longer Sick Building Syndrome, [because then you know the precise cause].

It tells us a lot about a specific moment in American construction, but the larger idea of buildings being “well” continues to have all sorts of contemporary applications. Even in the case of contemporary “green” buildings, which often fall into the same pitfall, as they’re trying to use all these new, untested materials in spaces with limited ventilation.

The migraine is a great example [of a similar problem]—it’s a condition that has a degree of complexity that’s too complicated for the Western medical system to comprehend. We’re very good at solving problems with a very simple causal relationship. You get an infection, we give you a prescription, the infection goes away. But the causal conditions of migraines are never that simple. It’s often a constellation of triggers. Time and again, Western medicine fails to address this condition that affects an enormous number of people, the vast majority of whom are women who are historically underserved by medicine.

TU: Your book considers the enduring tragic mythos surrounding architects, such as Henrik Ibsen’s The Master Builder—and the folkloric tendency to associate construction with human or personal sacrifice. Is there any truth to this, and if so, is it a self-fulfilling prophecy?

JB: If versions of this story of sacrifice are coming from so many different cultural histories, one tends to think there’s something fundamental about it, right? There are two myths at work here. One is the myth of the architect as a tragic hero. But then there’s also this tradition of sacrificing something or someone for a building, which has origins in the Balkans, Japan, and Germany—these very different societies have formulated stories that are variations on this idea of a human sacrifice required for the blessing of a large piece of infrastructure, and often in a symbolic way.

But of course, there are also stories of sacrifices made in a literal way. For example, the number of people who died in the casting of the Hoover Dam, because the dam construction had to proceed. Something about this piece of infrastructure represented value that surpassed that of human life.

Then there is the story of the architect as tragic hero—I wrote an expansion of that part of the book for The MIT Press Reader. I’ve always been interested in the myth of the architect, because it seems so narrow, and so reinforced at every level of culture.

From Ibsen in The Master Builder, to tropes within the romantic comedy genre—I confess to not being an expert, but it seems like there’s always this romantic lead who is an architect, who is more responsible than the artist, or more creative than the businessman, but somehow represents the best of all possible worlds.

So is this myth drawing somebody who is predisposed to these traits into this profession? And then, once they arrive there, how influenced are they by the weight of that mythology about the trajectory of their career? It is impossible to say.

For me, an important passage in the book is the moment when somebody tells me that I don’t look like an artist. That really stuck with me as this kind of awareness of the weight of the expectations of these archetypes. And with a lot of architects whom I know or have studied, the presence of this archetype is real in their consciousness.

A lot of that comes to bear in Yamasaki, who also happens to have these very uncanny relationships to the Master Builder of Ibsen’s play—the most obvious is that they’re both afraid of heights and build incredibly tall buildings. It’s almost uncanny, their similarities. By all accounts, however, Yamasaki was a much nicer boss.

Justin Beal is an artist and writer based in New York. He currently teaches at Hunter College. His first book, Sandfuture, was published by the MIT Press in September 2021.