This is the twentieth chapter in a long-simmering miniseries called “Narrative Architecture” about storytelling choices in fiction. There are many ways to tell a story, and in this series, I’ll examine the literary choices a particular author made and their impact on the story at hand. This week, I’ll engage with Kirsten Bakis’ novel Lives of the Monster Dogs, a modern classic that combines elements of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and H.G. Wells’ The Island of Dr. Moreau and throws them into the blender—before tossing the concoction into the Instant Pot.

This post is a revised version of an essay I composed as part of my MFA program at UNR.

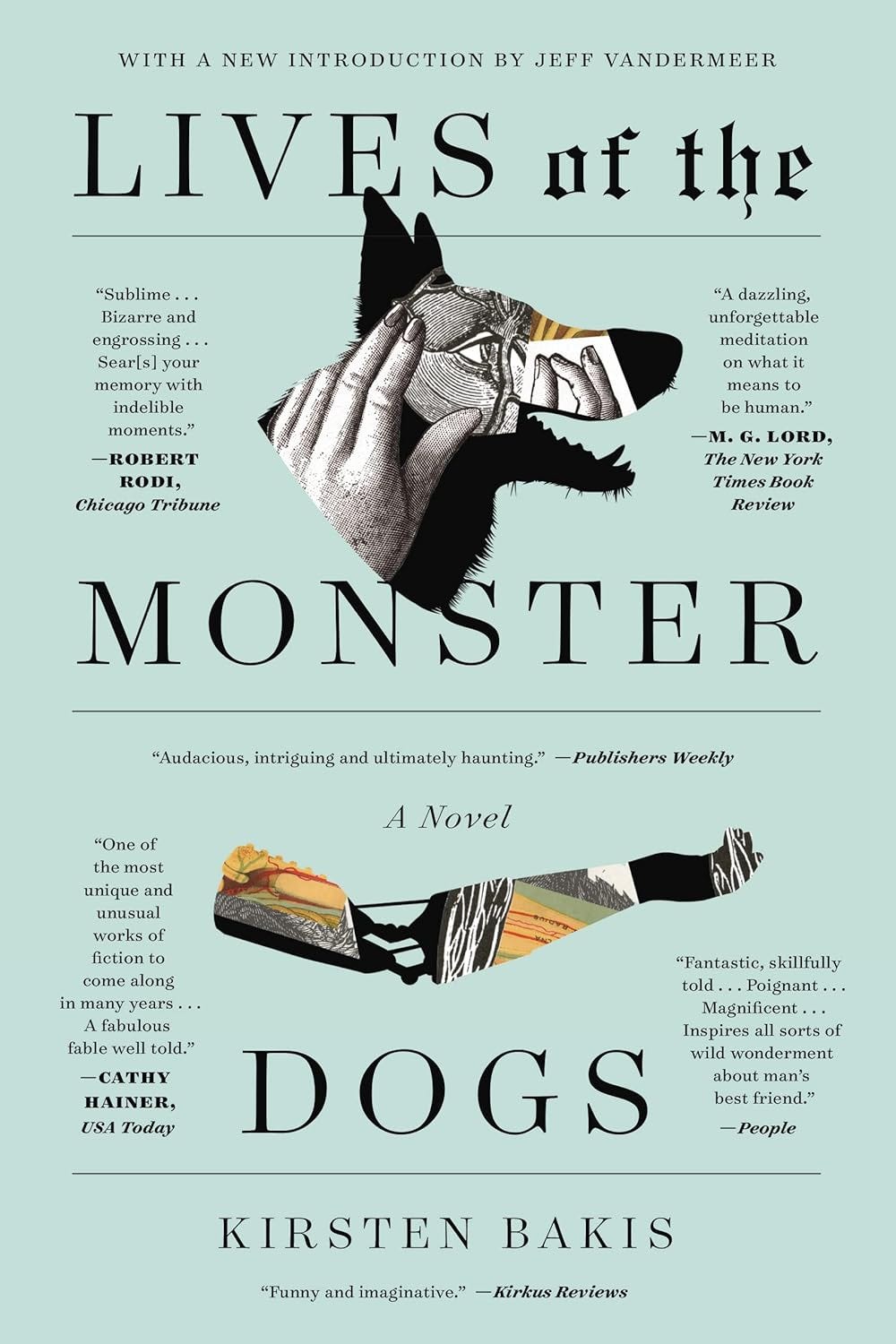

This is a book that should not work. There’s a reason Lives of Monster Dogs (LoMD) has been pretty much forgotten since its publication in 1997—it’s off-puttingly WEIRD. As Jeff VanderMeer notes in my edition’s introduction, this novel reimagines H. G. Wells’ Island of Dr. Moreau and Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein as a freakish saga of what happens after the events of the Island of Dr. Moreau, after animals with genetically enhanced intelligence escape the laboratory and try to integrate within human society. The twist is that Bakis’ “monster dogs,” equipped with handy steampunk voiceboxes and mechanical humanoid hands, move to New York and build a castle in Manhattan. Having been raised in the remote polar community of Rankstadt—which possessed a 19th century Prussian culture—the dogs dress in a Victorian fashion and speak in arch, antiquated sentences. There’s a ticking clock, too, as the dogs are progressively losing their intelligence, foreshadowing future catastrophe. Suffice it to say, there’s a lot to talk about in regards to this novel—probably too much.

Today I’ll focus on the novel’s most flashy rhetorical flourish—the in-text opera Mops Hacker, which reveals the backstory of the monster dogs at a critical moment—or, actually, it reveals the backstory of the monster dogs as interpreted by the monster dogs, packaged as a propaganda entertainment.

There’s a note at the beginning of the embedded paratext Mops Hacker: The Opera which tells you all you need to know about the tone of LoMD: “Place: Rankstadt, an isolated town in the Canadian wilderness… Time: September 1999, but the culture resembles that of Prussia about 1882” (190).

Bakis expects a great deal of readers in this book. Not only does she hope we’ll go along with the idea of a 19th century Prussian mad scientist—a somewhat familiar archetype—who manipulates the genetic structures of dogs, but that we should accept that this scientist does this for the purpose of creating “perfect soldiers” in the mold of a campy proto-Nazi. Then we are supposed to swallow that this mad scientist successfully relocates his laboratory to the remote Canadian Arctic, where his followers continue on with his project for the next hundred years, retaining the same cultural mores despite the passage of time. Here, Bakis is playing on so many levels that she expects us to approach this “remix” of Frankenstein and The Island of Dr. Moreau not just on the level of camp (though there is that, of course), but also as a serious novel more generally. As Vandermeer explains in his introduction:

…hybrids tend to be misunderstood and often have trouble finding an audience or sympathetic reviewers. Because hybrids are composed of both new thought and old parts, they seem to exist, on an elemental level, in uneasy contrast…. And yet over time this seeming lack of harmony gathers its own kind of symphonic powers.

In that sense, I think it is a miracle that LoMD was ever published and received so well.

One of the most successful elements of Monster Dogs is the aforementioned opera script, which comes at a climactic point in the story. The paratext is particularly interesting because not only does it offer exposition—the secret to the final mystery of the dogs’ revolution—but it also offers a mediated message. The opera is propaganda for the dogs, a literary interpretation of historical events that no one but the dogs themselves can verify. So while it offers an answer, it doesn’t point to a definitive one, and there is certainly some ambiguity in the telling.

One of the most fascinating ways Bakis uses the opera script is how it both celebrates and condemns its protagonist, Mops Hacker, as a revolutionary savior driven by madness, a psychopathic outcast who is also something of an “incel” (unrequitedly pining for the pivotal female dog character Lydia). In the opera, at least, Mops is demonstrably monstrous in character before he attacks, even compared with his compatriot monster dogs:

MOPS (Stirring but not waking). Cursed master, this morning I won’t answer you./But if only once I would answer you properly, with a sword!/Oh, what joy!/What joy to split his ugly head/And leave him lying there for dead,/To burn his house and all that’s in it,/To stand up finally to fight, and win it!/Oh, how I long to kill him (194).

To name an antihero as murderous within the text of the play is a choice, either reflective of how the dog-authors want to distance themselves from their genocidal liberator, or reflective of the “true Mops.” Either way, it is not the heroic protagonist we might expect in a traditional opera or play, as usually in this sort of tragedy, we might expect someone with potentially good qualities to eventually turn evil, rather than remain statically bloodthirsty the entire story.

Despite this deviation from convention, aspects of the opera seem to align with Shakespearean tropes. Just as Mops is about to kill himself, he sees the ghost of Augustus Rank, his creator (in the same way that Hamlet ambiguously “sees” the ghost of his father):

A golden cloud of smoke appears. In the center of it is AUGUSTUS RANK.

RANK. My son, stop.

MOPS falls to the ground in amazement.

MOPS. Augustus Rank! You have returned.

RANK. You call me master,/You alone among the dogs/Reject the feeble man who owns you/And long to serve me. (Bakis 196)

Notably, the opera is consistent with the previously-seen excerpts of Rank’s journals, which allude to Rank’s gold-tinged visions, such as after Rank murdered his romantic rival Vittorio:

Third, I saw a flash of light so brilliant that it blinded me for a moment, the same moment that the blood began to spurt out of Vittorio’s neck. I then saw that the luminescence was of a golden color, but brighter than anything I had ever seen, and it was only thanks to my newfound strength that it did not sear and permanently damage my eyes. For my body is stronger, too, since my enlightenment. (95)

Bakis’ interlocking narratives achieve some impressive synergies. Throughout the novel, the dogs are suggested to have inherited Rank’s soul, and that their pathologies might also be a result of Rank’s psychoses, which have passed along to his “descendants.” So when the dog opera references elements previously featured in “historical sources” also excerpted in the novel, it adds layers of complexity and verisimilitude that continue to build out this universe.

Adding additional complexity to the opera is the very Greek tragedy-type of dialogue between Lydia and Mops in the final sequence (which, naturally might also remind the reader of Star Wars):

MOPS. Lydia, snow-white Lydia, how beautiful you are!/For years I’ve desired you./Lydia, how I long to make you mine./The time has come./We’ve won./Together we can rule, we two, as one,/The victorious, free Nation of Dogs.

LYDIA. Never, Mops. (Bakis 214)

It seems very Darth Vader/Luke Skywalker for Mops to ask Lydia to join him and rule over the dogs—which goes without saying this exchange is unbelievably campy! It is an opera, however, a genre not given to subtlety. Bakis’ text-within-a-text can be ridiculous without notice because the premise of the entire novel is so absurd that this seems familiar enough to keep us going. In typical overwrought opera fashion, Lydia stabs Mops and ends the revolution, but only after all the humans in Rankstadt are killed.

And finally, one last point on the Monster Dogs. After the opera concludes, the book’s primary human narrator, Cleo, asks Lydia if the opera was factually accurate:

“And was that how it happened?” I asked Lydia, one evening after the opera… “Yes, more or less,” Lydia said. (219)

So while Bakis has sowed doubts about the opera’s accuracy, she also wants us to rely on the opera as the definitive origin story for the dogs in the book. Or, at least—that Lydia wants Cleo to think of her as the hero who killed Mops and limited the damage of the dog revolution.

Bakis’ paratexts are so complex, they are tour-de-forces when it comes to the very idea of paratexts.

However, it still seems curious as to why, then, did Bakis go to the trouble of writing an opera for the monster dogs? To my mind, the narrative decision represents the sheer experimentation of the book and Bakis’ commitment to making her book as hybrid a text as possible. I think this contributes to both the cult success and popular failure of LoMD.

As Vandermeer suggested, though the hybridization of genres makes LoMD exciting, the remixing can also turn people off, and makes LoMD lose its own identity as a footnote to the more famous works which have inspired it.

Works Cited

Bakis, Kirsten. Lives of the Monster Dogs (Farrar, Straus and Giroux: New York, 1997).