In Franz Kafka’s novel The Trial, Josef K. is arrested for a crime but is not permitted to know what that crime is. The novel is one of the principal reasons “Kafkaesque” has come to describe an unreasonable bureaucratic process.

I had some assumptions about getting established in Cyprus. One, that the Fulbright Program and the US Embassy would streamline the process. That Cyprus, being infamous for being the location of various money-laundering schemes and scandals involving selling EU passports to foreign criminals, might not be so difficult to navigate.

Well, it turns out that if you’re not a Russian mobster, you’re Sisyphus rolling that boulder uphill.

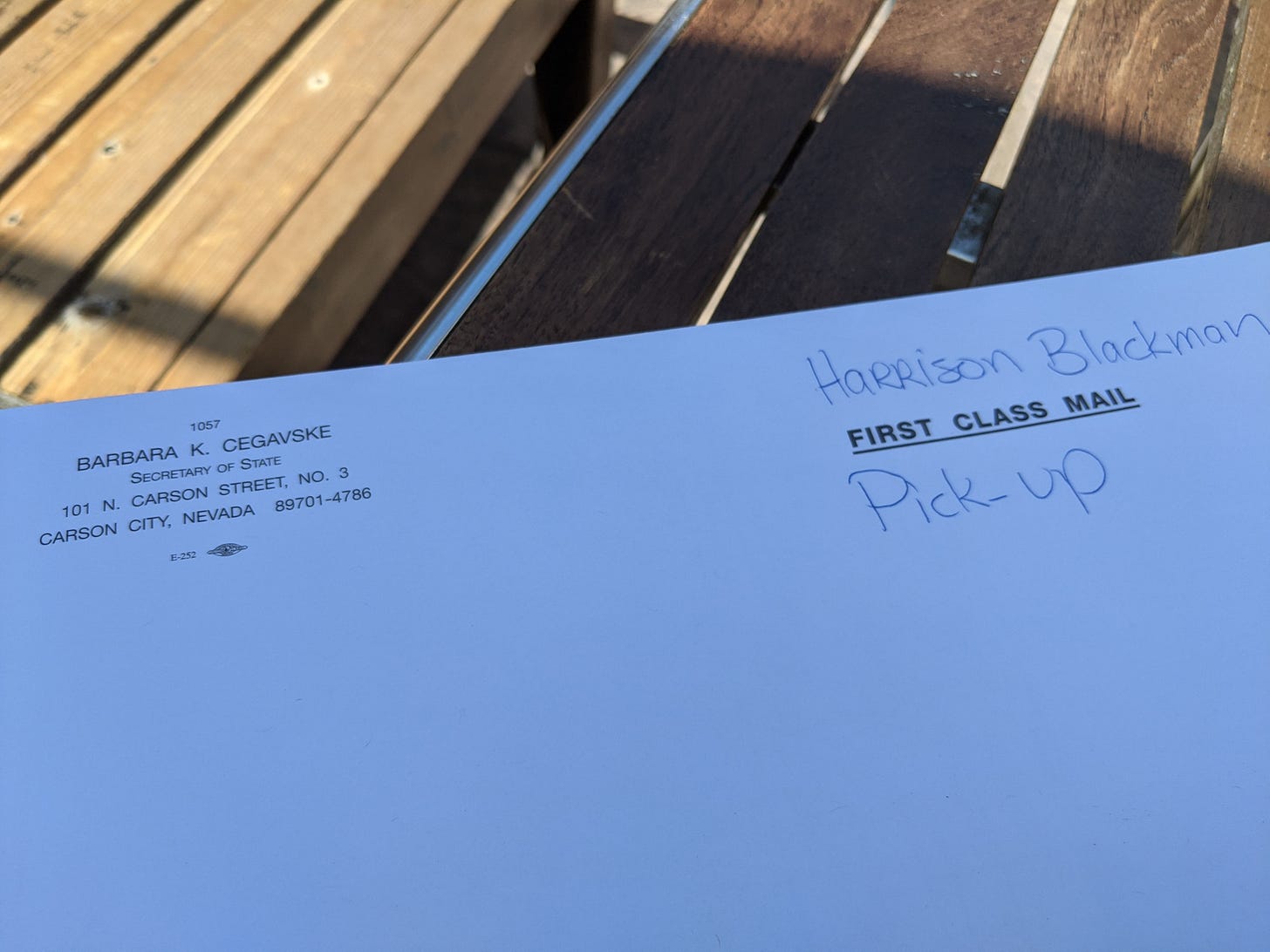

I also learned it’s just really hard to leave Nevada. You can check into the Grand Sierra Resort any time you like, but you can never leave.

What I Talk About When I Talk About… Apostillation

One of the requirements for an entry permit to Cyprus is to present “apostilled” documents, a process that perhaps most Americans are blissfully unaware of. Put simply, an apostillation is a special form of notarization that is recognized internationally thanks to a treaty signed at The Hague. You can get documents apostilled in your state capital, at the office of your Secretary of State.

Now, because almost literally no one knows what “apostillation” means, this meant that my forms kept getting botched. Admittedly, some of that botching was on me, but the notaries I consulted also made mistakes, and even the high-level notaries at the Nevada Secretary of State didn’t seem to know what I needed and what they were actually authorized to sign off on.

This problem was made worse by the fact I needed original criminal background checks (of myself, and no copies allowed) apostilled and FedEx-ed to Cyprus. These background checks took weeks to prepare—involving fingerprinting at the police station, arcane PDFs, and expensive fees. This process entailed several awkward trips and offbeat phone calls to the Washoe County Sheriff’s Office and the Reno Police Department, the “real-life” parallels to the parody cops on the sketch comedy show Reno 911.

In order for the Nevada authorities to apostille the documents on a timely basis (as opposed to their normal turnaround of 3-4 weeks), I had to pay additional fees to expedite, fees multiplied due to a string of bad luck.

Once, my forms were mistakenly sent by the post office to Connecticut. Another time, the notary messed up the form and Carson City officials casually whited-out the incorrect stamp on the form, causing the form to look quite unacceptable to the international authorities, forcing me to restart the process yet again.

More than once, I would drive all the way to Carson City, arrive at a dimly lit and nearly abandoned office, present the Secretary of State employees a document, and a notary would look at it (not very hard), and he would say, “we don’t do that.” I’d be like, huh? I’m pretty sure you do this, and if you don’t, could you please tell me where to go?

And then, after analyzing the page a little more closely, holding it up to the light, he’d be like, “you know, we actually DO do this.” In these moments I felt a rousing affinity for Larry David, the whimsical strings and brass of the Curb Your Enthusiasm theme playing in my head.

Life Takes Visa

Once in Cyprus, the visa application continued on in another level of absurdity. Even after I submitted all the requirements for the entry permit (background check, passport, research agreement, medical tests), I still needed to conduct a chest x-ray in a local private hospital, get more blood work (I had already done blood work stateside for this purpose), and have those results certified by the Ministry of Health. At the very least, I am absolutely confident I do not have TB.

In the health department, my American compatriots and I encountered dark hallways and overstuffed filing cabinets and piles of paper gathering in the shadows of fluorescent light, documents either critical to someone’s future or otherwise completely meaningless. Thankfully, our own papers were stamped and signed without incident.

Finally, at the Migration office, we turned over our paperwork, took photos and fingerprints. Collating the pages in her hands, the official handling my case told me, maybe we’ll have a visa for you in three to five months.

The Bank Account

To open a local bank account in Cyprus (so as to avoid constant and insidious money conversion fees to the Euro), you need… a lot of paperwork. Some of these items are obvious. Others—not so.

— Your visa or receipt of that visa application. (I obviously didn’t have the visa at this appointment).

— Passport.

— An apartment lease document signed by you, your landlord, two witnesses, and certified (by a “certified person”, the equivalent of a notary, except this is a bit harder than normal because the banks don’t keep notaries on staff).

— An utility bill with your name and address. However, to set up utilities, you need a bank account, setting up an epic “Catch-22.”

— Your work contract with a local institution and indication of your salary.

Once I had gathered these items (some of them more difficult than others), I waited in line. Cypriot banks give new meaning to the idiom “working banker’s hours” because the bank is only open from 8 to 2:30 PM. And when they say 2:30 PM, they really mean 2 PM, because that’s when the manager started counting the money behind the counter and locking up. At that moment, I began to note the palpable anxiety gather in the bank when all the people in front of me were being turned away. “Θα γυρίσεις το αύριο,” a teller urged another would-be migrant. (Come back tomorrow). “There is nothing we can do—the bank is closed.”

When a different teller (who had been handling my case) finally called me to the counter, the bank was deserted. She then had me sign and initial what seemed like 40 sheets of paper. Then she said we were finished, and directed me out the back door. Τέλεια! (Perfect!).

I am grateful for the generosity of this teller, and recognize that if I wasn’t from the United States, maybe I would not have been treated so kindly.

In Conclusion

One of the “joys” of the Fulbright experience is learning the ins and outs of how another country’s system works. It also gave me a taste of what the US makes immigrants and migrant workers go through in order to come to America.

(Of course, the US Embassy did streamline the process. After recounting the hoops I’d jumped through to some friends who had previously conducted Fulbright grants in other countries, they told me they never had to do anything like what I and my fellow Cyprus grantees were up against.)

That being said, I am tremendously grateful for this experience and the chance to learn and build “mutual understanding.” Plus, I’m in Cyprus now. It was worth it.

The process also made me realize that the Nevada system isn’t much better, but heck, I knew that already.

This is the third post in The Cyprus Files, a limited-run newsletter series from The Usonian chronicling my Fulbright experiences in Cyprus. You can read all the posts in The Cyprus Files here. Thanks for reading, and don’t forget to subscribe so you don’t miss a (free) dispatch from the island of Aphrodite!