In Texas, a tale of two cities

The divergent trajectories of San Antonio and Austin

This post was previously published, in slightly different form, on Medium in March 2020—yup, right before the lockdown. As I rescue my writing from different corners of the internet, perhaps these pieces will find new life within the virtual pages of The Usonian.

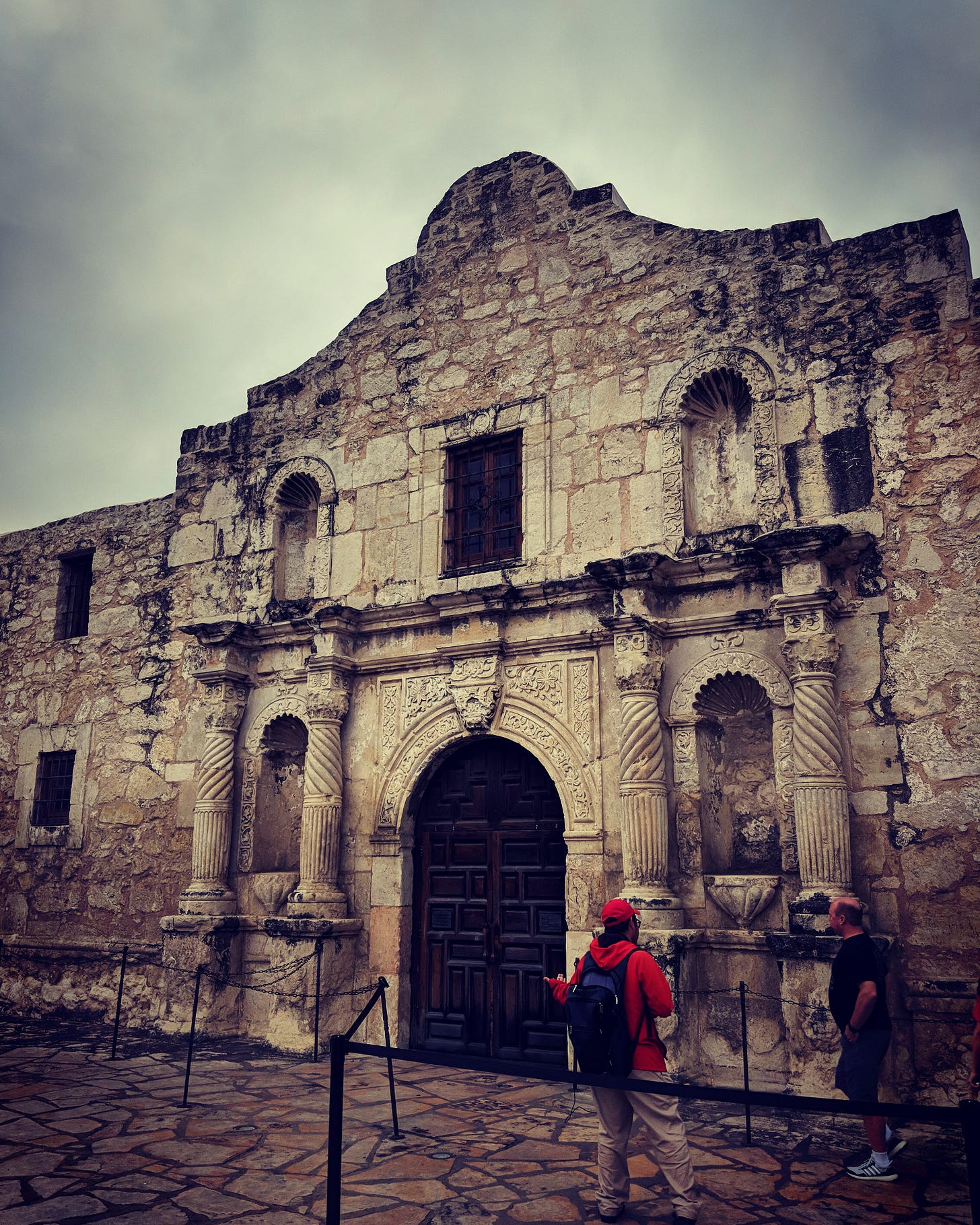

AUSTIN, TX—Everything is bigger in Texas. Except for the Alamo, that is. Perhaps it is telling the state’s most iconic landmark is smaller than you’d think. Perhaps it’s telling that, across the street from the historic mission chapel and battle site, is a “Tomb Rider 3D Adventure Ride and Arcade” and Ripley’s Believe it or Not.

The Alamo may be the most famous landmark in Texas, but it’s also indicative of the nature of San Antonio, a sprawling urban area that somehow doesn’t feel crowded. The city’s old-world, touristy vibe contrasts mightily with the burgeoning, gleaming city just 79.5 miles away: Austin, capital of Texas, the fastest growing metro area in the United States.

If San Antonio offers a glimpse of Texas’ past, Austin might just yet be a glimpse of its future.

San Antonio: Out of the Past

San Antonio is the seventh-largest city in America, but you wouldn’t know it. The city feels sleepy. San Antonio’s architecture is grand in places but unassuming in others. The city sprawls but never feels loud. While San Antonio is vast in population—1.49 million, it hosts only one big-three sports team, the NBA’s world-renowned, dynastic Spurs.

In San Antonio’s central plaza, old men sit in the square facing the Cathedral of San Fernando—established almost 300 years ago. You might be as well be in Argentina or Spain. One half-hopes some men might be playing bocce, or at least try throwing a metal ball in the dirt.

The famous River Walk, first envisioned in 1929 but constructed in 1946 and extended most recently in 2016, evokes the romance of Venice—until you find the Rainforest Café, Bubba Gump, and Hard Rock Café. (To be fair, Venice also hosts a Hard Rock).

Then you realize that postwar San Antonio was just on the cutting edge of tourist trap architecture, a Texas version of New York’s High Line well before its time. It’s landscaped beautifully, and for $13.50 you can hop on a tour boat for a thirty-minute cruise past one bougie hotel after another. What a brilliant real estate gamble it was, to extend the extant river into a loop-de-loop, to plant plenty of flowers. Build it and they will come. They did. In fact, they still do.

Part of the River Walk was extended in time for the 1968 World’s Fair (the cringeworthy-titled “HemisFair”), which was also motivation for the construction of the “Tower of the Americas.” In hindsight, it doesn’t make sense why San Antonio wanted their own Space Needle, especially because this one is so ugly.

For a taste of San Antonio’s contemporary redevelopment efforts, there’s The Pearl neighborhood, a renovation of a century-old brewery. Craft coffee, beer, and luxury apartments give the sense that a brand-new Washington, D.C. condo complex hath landed in Texas. Gentrification is truly everywhere, and not even San Antonio has been spared.

Deep Time

For a more pure historical experience, one might drive down to the Mission San José, part of a chain of missions extending some 35 miles south. Within the courtyard of this beautiful ruin of a church, one can imagine a colonial culture on the frontier, barricading gates as they warded off Apache warriors. The imperialism of the mission system is a tragic history, but a fascinating one.

I’m going to oversimplify, but here’s that history in a nutshell: In 1691, Spanish missionaries and conquistadores explored the area for the first time, arriving in time for the feast day of Saint Anthony—hence, the city’s name. Meanwhile, the Payaya natives had lived there for centuries. It wasn’t until the late 1710s that the Spanish colonized this area in earnest. Missions were established to convert natives and protect the settlements against raids by rival tribes. Once the locals had been sufficiently ‘converted,’ the missions would become secularized and sold off to private interests. This process—at the Mission San José, at least—was complete by 1824 (post-Mexican independence).

The Alamo was one such ‘privatized’ mission when it became a fort for ‘Texians’ (Anglo-American and Mexican residents of Texas) rebelling against the Mexican caudillo (military dictator) General Antonio López de Santa Anna.

That’s where, in 1836, William Travis, James Bowie and Davy Crockett and between 179 to 254 others died in battle (the sources aren’t great—since basically everyone defending the fort died, it’s a bit difficult to keep track).

That battle is what motivated Sam Houston’s 1836 victory over Santa Anna in San Jacinto and resulted in Texas independence (until its 1845 U.S. annexation), part of the lead-up to the Mexican-American War. That’s why people remember the Alamo today, and remember to visit its gift shop, which seems larger than the Alamo chapel itself.

Enough of history. Let’s talk about the future.

In one way, San Antonio might represent the majority-minority future of the United States: Fifty percent of San Antonians are Hispanic—non-Hispanic whites form only 25% of the population.

But if we’re going to talk about Texas’ future more broadly, we need to travel 79.5 miles north, to a confluence of market forces and cultures that could only exist in Texas.

Austin—city of the future?

In San Antonio, the crosswalks sometimes talk to you in both English and Spanish. In Austin, they count down in the voice of J. R. Ewing.

If San Antonio is an old-world tourist destination, Austin is the confluence of Portland-styled hipsters with the gentrification of Brooklyn, combined with the music scene of Nashville. Austin is the fastest growing metro in the United States and it shows. The result is decidedly a Texas city for the 21st century.

Rising from the banks of the Colorado River (not to be confused with its more famous cousin), Austin’s waterfront is a glittering panoply of new towers punctuated by The Independent, a precarious-looking stack of luxury condos. The building, completed in 2019, is derisively known as “Jenga Tower” by some Austin residents. As it resembles a tower in a state of collapse, it is easy to see the source of such ire.

Austin possesses all the beer gardens and Edison-bulb cafes to fill an entire state. Yuppies and hipsters alike walk their dogs to cafés such as Better Half Coffee, adjacent to a brewery, picnic tables forming a common space between them. Meanwhile, UT-Austin students take a break from their studies and hit up some of the many beer gardens on 6th Street, blocked off at night like New Orleans’ Bourbon Street.

In East Austin, home of Bernie banners and CBD boutiques (marijuana isn’t legal in Texas), hipsters rule the day where yuppies might elsewhere. At La Barbecue, one of the cities trendy barbecue eateries, weekend lines stretch out the door.

Austin is the fourth-largest city in Texas, but it feels bigger. If San Antonio feels somnambulant, Austin is throbbing with life, death, buzz, and suffering. It is a city, in all the messy connotations and complications of the word. It is cultural. It is bustling. It is government. It is also Texas.