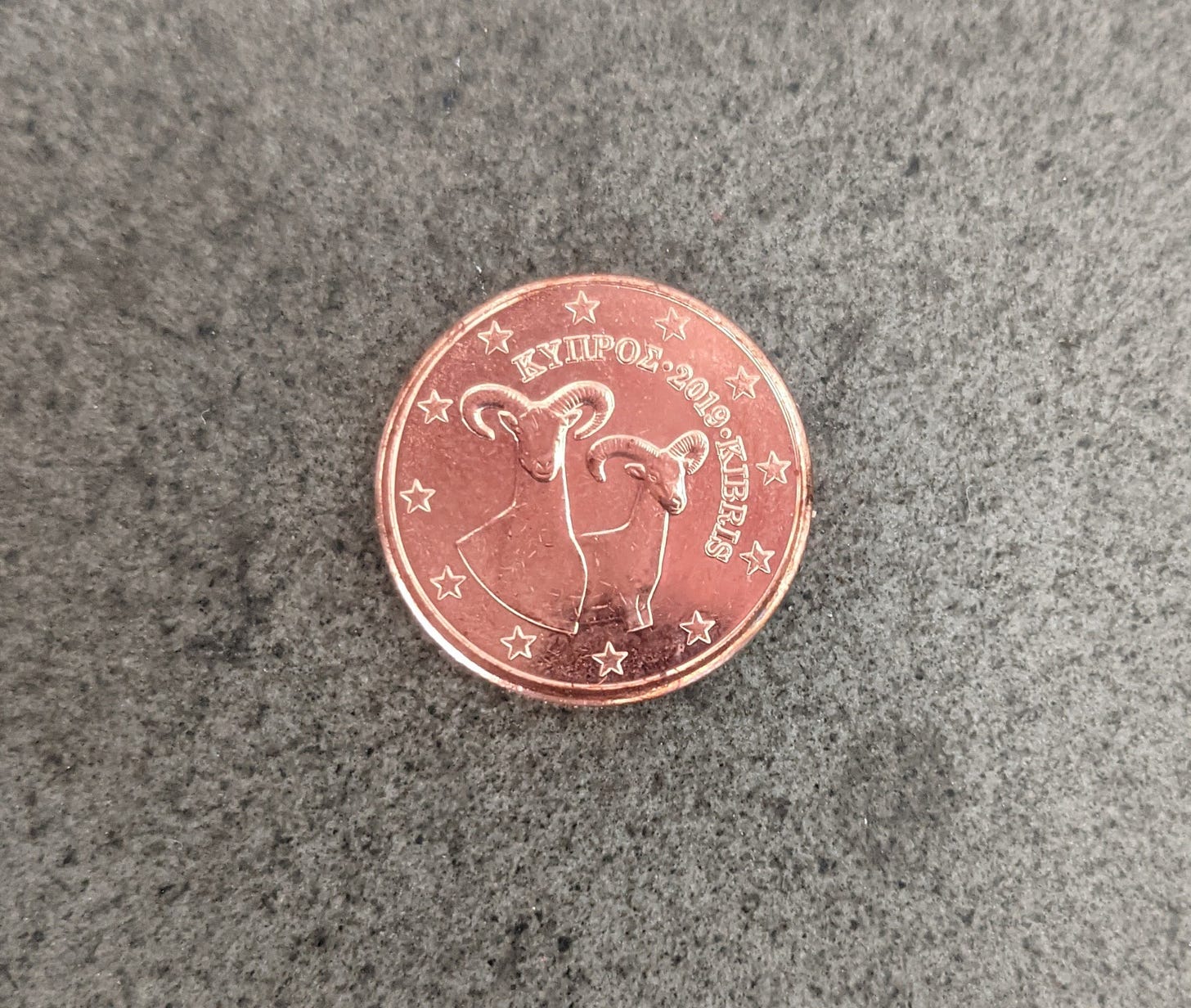

I had long heard tales of the mouflon. In Cyprus the symbol of the mountain sheep is everywhere. You can find statues of it on main streets, statues at monasteries high in the mountains. An important bookstore in Nicosia uses it as its namesake. The EU penny’s Cyprus variety has the animal on its coin. When Cyprus had an airline (defunct for a while, but recently resurrected), the sheep’s head was its logo. In metaphorical and symbolic ways, the mouflon is everywhere—but at the same time, the real-life mountain sheep remains elusive.

A threatened species with an ancient heritage, the mouflon is one of those charismatic species that takes on a life of its own—even when its own life was almost extinguished.

Sheep of the ancients

The mouflon’s scientific name is Ovus gmelini, and its modern name may derive from the ancient Greek, “ophion.”

Thought to be the ancestor to all domesticated sheep species, the mouflon is native to the Near East and Central Asia. It’s possible the sheep arrived to Cyprus in the Neolithic period, brought to the island by settlers from Asia. But Cyprus was also home to pygmy hippos and dwarf elephants until these mini-megafauna went extinct at about 11,000 B.C.E. Perhaps before that time, the mouflon had already made their debut on the island.

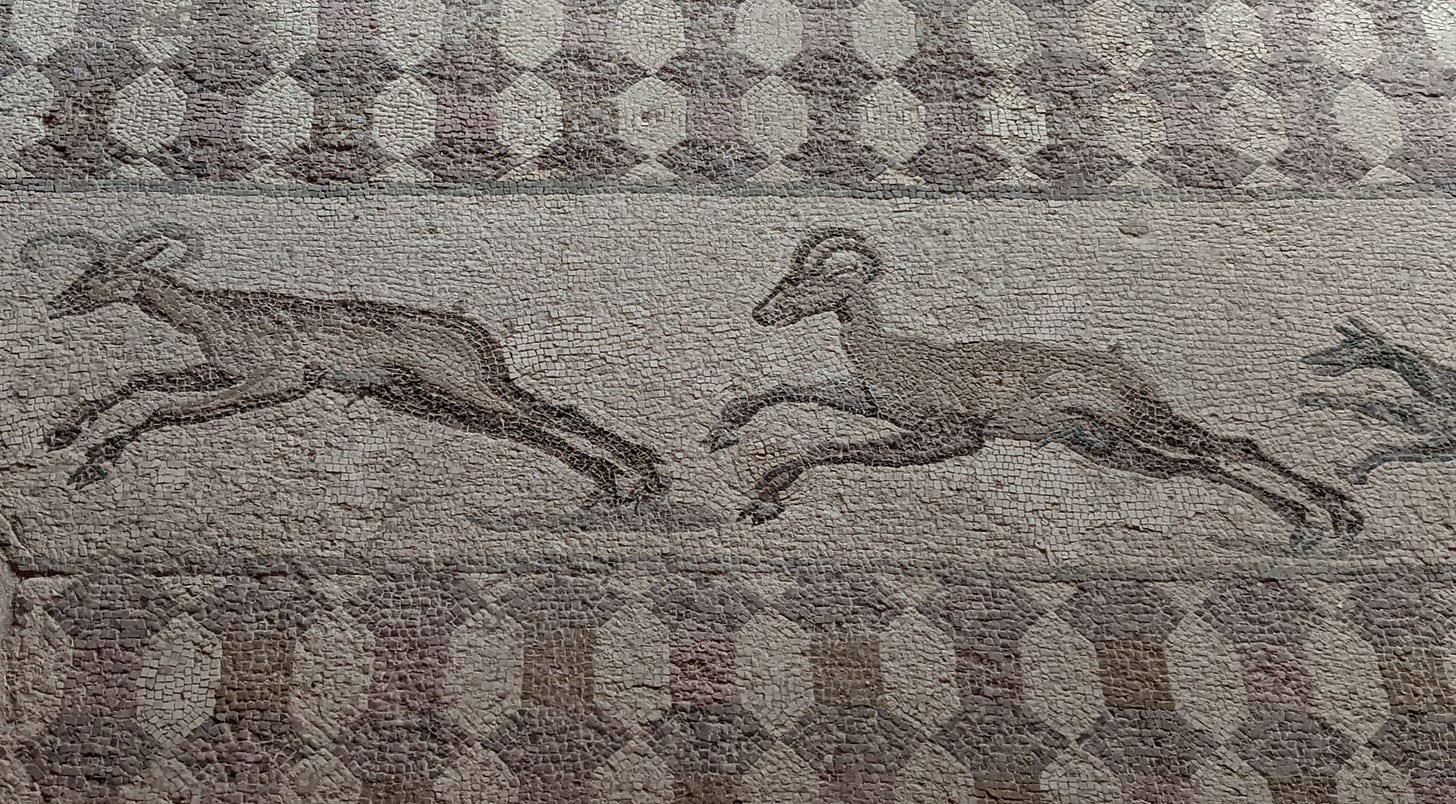

Regardless, the mouflon was an important animal in prehistoric times for Cypriots, and during the period of Roman control of the island (starting at 22 B.C.E.), the sheep’s existence was celebrated with floor mosaics in Paphos.

And though the mouflon had great longevity on the island, hunting had nearly extinguished the mouflon by the end of the Ottoman period in Cyprus, a time in which hunting was unrestricted. When the Ottomans handed over the island to British administration in 1878, there were only 15 mouflon left on the island. British conservation management helped the mouflon bounce back, especially in the mountains of the Paphos region.

Mouflon have become a symbol of modern Cyprus since the Republic of Cyprus’s independence in 1960. Today, there are about 3,000 wild mouflon on the island, but the species remains a threatened species in Cyprus and is endangered on other islands, such as the Italian island of Sardinia, where the sheep has been cloned as part of conservation attempts.

The apparition

My quest for mouflon, over my time in Cyprus, felt fraught. On hikes, jogs, and other excursions, I had encountered snakes, lizards, birds, fish, and donkeys, but no mouflons.

That is, until one day in April, when, as my car rounded the highway near Aphrodite’s rock, I thought I saw them.

A herd of goats, stumbling across a cliff above the freeway. Could it be? Had I found the elusive mountain goat? They did possess horns. But no sooner had I witnessed these creatures, did I drive around a bend, and they were out of sight, instilling doubt in my mind.

For a moment, I thought I had finally spotted a herd of mouflon. But as my excitement faded into rationality, I realized that what I had seen were in all likelihood just a group of regular goats, a shepherd’s errant flock, as I had often seen in other rural situations on Cyprus. The dream of seeing a mouflon remained just that. My quest for the elusive mouflon—it would never end.

This is the twenty-fifth post in The Cyprus Files, a limited-run newsletter series from The Usonian chronicling my Fulbright experiences in Cyprus. You can read all the posts in The Cyprus Files here. Thanks for reading, and don’t forget to subscribe so you don’t miss a dispatch from the island of Aphrodite.