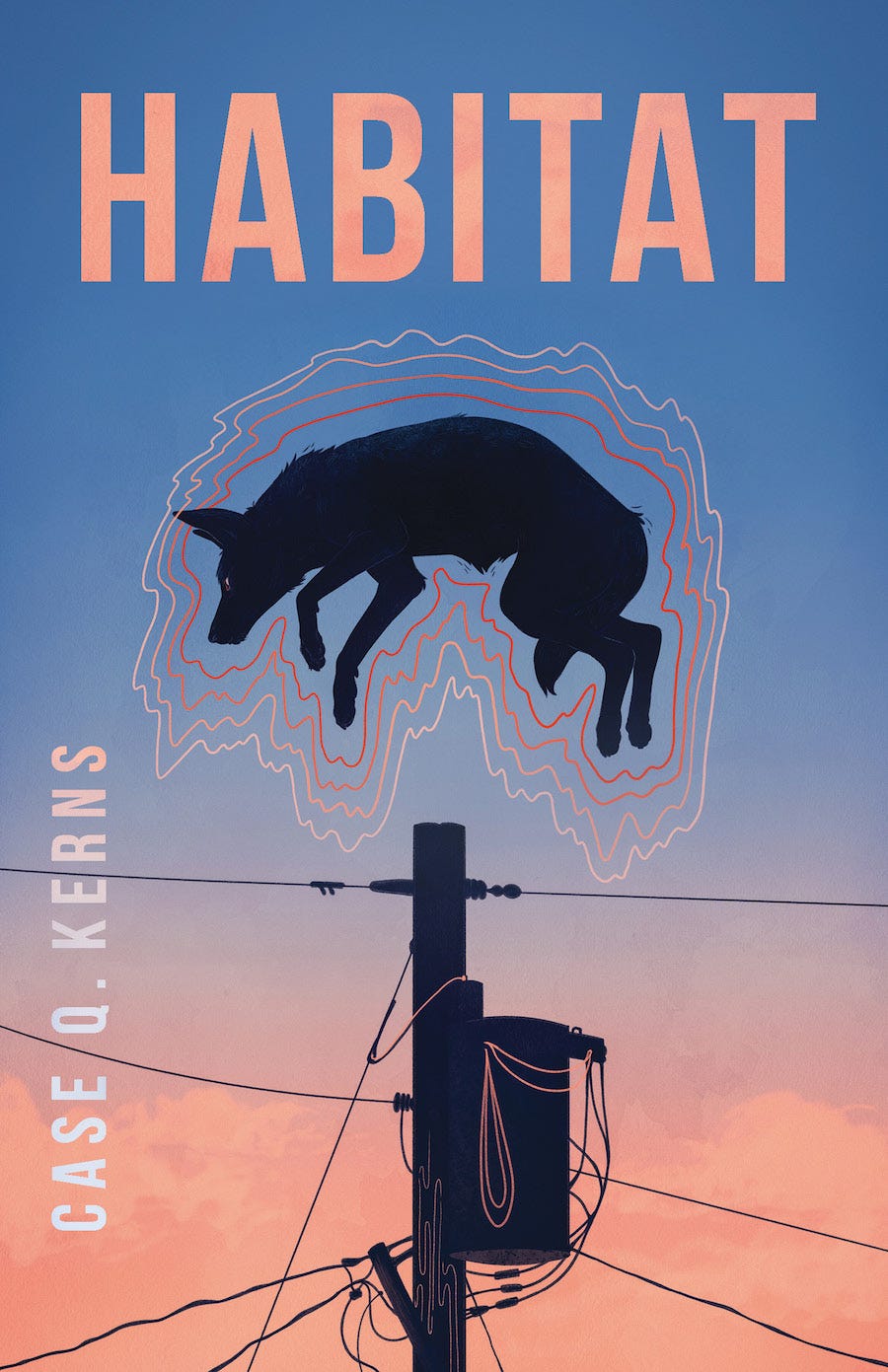

Case Q. Kerns's "Habitat"

An inventive debut sci-fi novel reminiscent of David Mitchell and Philip K. Dick

In each installment of “The Usonian Interviews,” The Usonian spotlights a storyteller from a different corner of the globe. This week, The Usonian spoke with Case Q. Kerns about his debut sci-fi novel, Habitat.

Set in a dystopian world where citizens vie for scarce educational sponsorships for their children, a subculture of people seek to collect transplanted human body parts, and sinister corporations clone popular dog actors to create the ultimate must-have Christmas present, Habitat is a novel made up of interconnected stories that jumps forward in time, where the nightmare of the present becomes a cataclysmic future, and the echoes of the past keep resounding from generation to generation in ways that both haunt and entrance.

You can order the book directly from Black Lawrence Press, Bookshop, Barnes & Noble, or Amazon.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length. The views presented by the interview subject are the opinions of the subject and do not represent the views of the article’s author or this newsletter. Browse the full interview archive here.

THE USONIAN: Habitat is an exciting novel of interconnected narratives, embracing aspects of science fiction and fantasy. Set in a near future where middle-class people scramble to acquire educational sponsorships for their children, and off-brand clones of a dog starring in a Star Trek-esque TV show are available for purchase, the novel jumps through time and characters in a way that is reminiscent of Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle, David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas, all in a Black Mirror-suffused world that never forgets its strong, struggling characters coming up against the limits of their dystopian reality. What inspired you to write this novel, and how did you come upon Habitat’s innovative structure? Did you write and conceive of these stories separately, or did you plot it all out at once?

CASE Q. KERNS: I didn’t plot it all at once. I had written a novel that was a sci-fi noir with a first-person narrative style similar to Raymond Chandler or Dashiell Hammett, but it was weird—a parasitic mollusk attaches itself to the narrator and then increasingly affects aspects of his life, such as memory and appetite, throughout the novel.

When I finished it, I sent it out to a bunch of agents and presses, and I got great feedback from agents about my writing and use of blending genres, but no one was interested in representing the project.

Instead of sending it out more broadly, I decided to set it aside, because at that point, I hadn’t had anything published. So, I started writing short stories to send out to journals and magazines.

Three or four short stories in, I wrote “Potluck Barbecue,” which became the second story in Habitat. After I finished writing it, I was intrigued by the world. I wanted to continue exploring this world.

Though I considered expanding that story into a novel, I didn’t want to go against my plan to write some shorter pieces and send them out.

So I decided to write more stories set in that world without any initial ambition for them to become a kind of collective piece, like a novel. But after two or three more stories, they started working together, and some of the stories started making connections with each other.

I wrote "Our Day Will Come,” about a mother who, while in prison, donates her foot in order to get her daughter an education voucher. After that, I was curious to write about the people who wanted these body parts. And that’s when I conceived of and wrote “The Man Who Knew the Collage,” which introduces this subculture of people who turn themselves into collages by getting anatomical donations from living donors. Shortly after that, the conception of the company Phyla that clones animals emerged, which plays a large role throughout the book.

From that point on, it became clear to me that this world of stories was moving in a single direction to form something bigger. When I finished rough drafts of the final two stories, “The Salt Box” and “Spare Part,” I felt it was coming together collectively more like a novel than a collection of stories.

Early on, I was listening to the Neil Young album Trans; on that album there’s the song “Like An Inca.” In the opening lines, a condor and praying mantis observe the downfall of a human civilization. Those lines are the epigraph to my novel, with animals being the victims of this world, and witnesses to so much destruction. From then on, I began plotting out the whole book. I thought about what else does this need, and how am I going to develop this further? Then it really started to gel together.

TU: From a near-future tiger safari to various tribes struggling against each other in a post-apocalyptic setting, the novel explores the relationship of humankind to nature. For you, what is it about the concept of “habitat” that unifies these stories together?

CK: My wife helped me come up with the title. I was having a tough time because the book is so fragmented. She observed the many different habitats, real and simulated, throughout and the role they play in defining the book.

One of the things present throughout is the way I illustrate our environmental and ecological crises more explicitly through extinction than, say, climate change. Animals are victims of human civilization throughout Habitat.

There are habitats forced upon people and animals and some that are voluntary. As far as those forced, there’s Jolene’s prison sentence in “Our Day Will come.” Edward, from “The Man Who Knew the Collage”—both his family’s estate and the Phoenix Club itself contain him—both centers of privilege even though he declares what amounts to a culture war against his family. Despite these domestic rebellions, he never disavows his privilege in any way.

The book also features “voluntary habitats.” The biotech mogul Alistair Holt lives in his “Old Dartmouth” recreation [of colonial New England], which provides his escape from the real world.

In the final story, “Spare Parts,” new habitats are established in a postapocalyptic future. There’s the Phoenix Club, the Winthrop Clan, and Holyoke—these different developing habitats are adjusting to a world where all these cloned animals and their descendants are now out and in the wild.

TU: Habitat is told in a spare, direct style, with precise description that also leaves a lot to the imagination. As a storyteller, who are your influences and how did you choose to pursue this style?

CK: My ideas and plots are typically a mix of genres that tend towards the weird. I feel writing in this direct, spare style makes it a little easier to embrace the worlds that I’m creating.

J.G. Ballard has been a big influence on my writing. I admired the way he explored his ideas in different settings and subgenres. He wrote a series of climate fiction novels in the early 60s, and then in the late 60s and early 70s, shifts, starting with The Atrocity Exhibition, and then Concrete Island, High-Rise, and Crash, which focus more on urban and suburban dystopian landscapes and the effects of technological advancements than ecological postapocalyptic settings.

That period appeared to influence his later work as well, but he never stopped tweaking his style and genre to better fit whatever ideas he was inspired by—he never got tied down.

And there’s Jeff VanderMeer, whose Southern Reach novels heavily influenced me. His blending of surrealism with the idea of a rapidly shifting nature has had an impact on my writing.

I also love Jim Shepard’s stories. He writes these great collections of historical short fiction, filled with memorable characters and incredible prose. The historical worlds he creates have influenced my approach to world-building in my own writing.

And there were two books I thought about while developing the structure of Habitat. Revenge: Eleven Deadly Tales, a collection of linked stories by a writer named Yōko Ogawa played a large role in helping me think about the movement and transitions between linked stories. Then, Sequoia Nagamatsu’s novel-in-stories How High We Go in the Dark, which is a series of what would work as individual stories, but together become a powerfully imaginative and chronological narrative.

TU: Several of the stories in Habitat lean into the setting of New England; notably, Alistair Holt, the CEO of the nefarious Phyla company, has a keen interest in the early Massachusetts Bay Colony, collecting Wampanoag artifacts and studying events like King Philip’s War, a 17th century war between indigenous and colonial Americans, a conflict that resulted in the near-total elimination of the Wampanoag tribe. Why did you choose to so richly ground the setting of a futuristic story through a character’s fascination of a distant past in the same terrain?

CK: In Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle [a novel about a world where the Allies lost World War II and the U.S. is occupied jointly by Japan and Germany], many of the Japanese occupiers are obsessed with American culture. When I think about that novel, I think about the antique store [selling U.S. Civil War artifacts to Japanese buyers] and that kind of obsession.

Why would people be fascinated with these objects? It seems like a material fetishization of history—if you just focus on the objects and not the people or events, it becomes almost like a trophy, something you don’t have to think too deeply about.

Having lived in in New England for a long time, the place influences my ideas and my imagination. Ultimately, I’m an American writer who writes stories set in America about Americans, and I want to cover as much of this world as possible. I feel obligated to cover the good and the bad—King Philip’s War and what happened to the Wampanoag might be considered one of “America’s original sins.”

The conflict preceded the establishment of the U.S. government by occupying a culture, and it’s part of the history of the world Habitat exists in. It feels dishonest not to acknowledge it, and dishonest literature attempting to ignore those aspects of history and existence that we’d like to forget is the worst kind of writing.

TU: On a similar note: Time echoes and cascades in Habitat, where characters in one story, like Winthrop, who is trapped in an apocalypse bunker, become legends in the next story, set sometime after. It reminded me of other novels, like the Dune series, where place names change and fragment over thousands of years. How do you think about time?

CK: I had an idea for a collection of linked stories years ago. The idea was that it would be these linked stories all taking place on a specific plot of land over time. The concept of the first story was set on the brink King Philip’s War, and the later stories ended in the future. The plot of land was in New Bedford, Massachusetts.

I had written drafts of a couple stories in that project, but then I read the graphic novel Here by Richard McGuire [later adapted as 2024 movie by Robert Zemeckis], which is this amazing book that covers millions of years in the same concept—this little plot of land in the past and future, and it’s 300 pages of panels set on this single piece of land. It’s incredible.

After reading that, I lost interest in the idea, because I felt it had been done better by Richard McGuire. But I repurposed some of the ideas from that project, especially those focused on the past and future, into Habitat.

I also had an idea that’s connected to Habitat that I ended up not writing or including in the book. In “The Salt Box,” Alistair Holt’s character mentions that he had found a journal in New England that documented his construction of a saltbox colonial house, and that’s what he used to build his reconstruction.

I have this idea to actually write those journals. There’s an incident that happens, creating tension and motion in the story, but within that framework of the journal, he would be documenting his building of this house. However, I didn’t feel it would be good for the book to start with a novella and then have all these other pieces. It’s bouncing around my head, and I hope to write it at some point.

In conceiving some of these stories, I was thinking about what would the past and future of this world be? This led me to develop ideas taking place before and after the near future present that composes most of Habitat, like bookmarks expanding the brickwork of the world.

TU: There’s a recurring theme of the transplantation of body parts in this book—either in exchange for educational sponsorships or to become initiated into a futuristic tribal society—and with companies like Neuralink experimenting with transhumanism, it feels like those ideas are not as far-fetched as they used to be. What drew you to this theme and what do you hope readers get out of it?

CK: As I mentioned earlier, in writing “Our Day Will Come,” I was thinking about the people who wanted these transplanted body parts. Combined with the advancements in animal cloning in this world, it seemed inevitable that there would also be the ability to clone human body parts. And in that case, why would someone choose a donation from a living donor, as opposed to cloning their own body part?

I started thinking about this privileged kind of subculture where the desire to take body parts from living donors when those purchasing the body parts had the means to have their own body parts cloned. It suggests the desire to control and consume bodies—specifically by breaking them down and transforming them into living organic trophies, or in this case, collages of what the purchasers taken from others. And I felt that that was kind of the ultimate and most troubling kind of control—pure control of the physical body as a form of power in this world.

TU: There’s also a fantasy element in the story, one involving a magic (and seemingly cursed) whistle, which is invoked in a couple of stories, most memorably in a suburban barbeque set-piece. What’s your approach to combining different genres?

CK: I just love weird literature and writers like Ballard and VanderMeer, and I like being able to move in and out of different genres. In Revenge by Ogawa, she has very short stories that almost walk into each other, seamlessly—some are fantastical and surreal, and then some are more realist, and they never feel out of place. The tone adjusts from story to story, and it never feels awkward.

Initially I thought it was just going to be in one story, and I had liked the idea of knowing that this thing was present, but never came back. The entity adds layers and texture to the world, blending the surreal, fantastical, and the real.

TU: You mentioned that you are working on another novel. Want to give us a hint about what that might be?

CK: I’ve written only about 20,000 words of a draft for a new novel titled Acropolis, set in a fictional city in New York state called Acropolis, New York, located somewhere between Troy and Ithaca in 1996. It’s a sci fi horror novel about an extraterrestrial parasite that rains down on the planet and creates “hives” of people that are physically connected to each other. It’s so widespread that no government shutdown is possible. So, this little town is forced to deal with the parasite itself, alongside all the small town personalities, relationships and conflicts. The story becomes largely about how the town reacts to the crisis—some people want to destroy the hive, and some people want to preserve it, to see if they can save it.

TU: Sounds like a parable for our times.

Case Q. Kerns is a writer from Buffalo, NY. He received a degree in Cinema & Photography from Ithaca College and an MFA from Emerson College where he served as fiction editor for the literary journal Redivider. His work has appeared in The Literary Review, The Harvard Review, and West Branch. Habitat is his debut novel. He lives in Massachusetts with his family.