A hundred years an architect

The last interview with international architect Athanasios Hadjopoulos

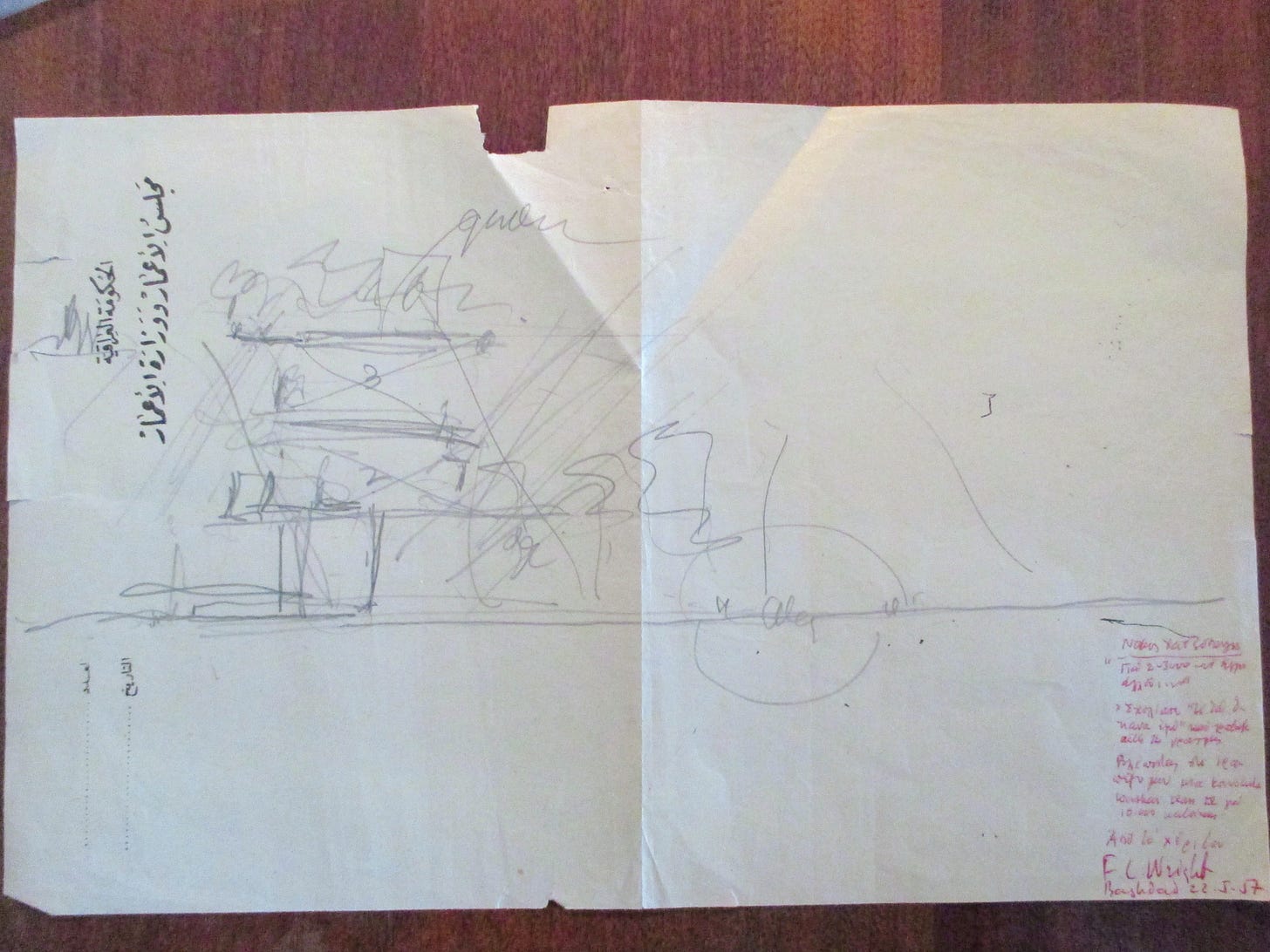

The Greek architect Athanasios Hadjopoulos was almost 40 when Frank Lloyd Wright stood over his drafting table in Baghdad. Wright, ever the irascible American icon, pointed at the plan on Hadjopoulos’ desk and asked what it was. Hadjopoulos explained it was a design for a low-income housing project to be built in the Iraqi capital. “You know, I wouldn’t do this,” Wright said, grabbing a sheet of paper and hastily sketching a three-story building with roof garden. “I would have done it like that.”

Hadjopoulos then did the unthinkable—he challenged Wright. He said that the project was meant to house 10,000 people. What, then, was the capacity of Wright’s plan?

“Two to three thousand,” Wright replied. “What about the rest?” Hadjopoulos asked.

Wright shrugged. The great architect didn’t care.

That was in 1957. In 2018, Hadjopoulos pulled out Frank Lloyd Wright’s drawing and put it on the desk in front of me. The frayed paper wasn’t even in a plastic sleeve, and suddenly I was touching Wright’s distinctive handwriting.

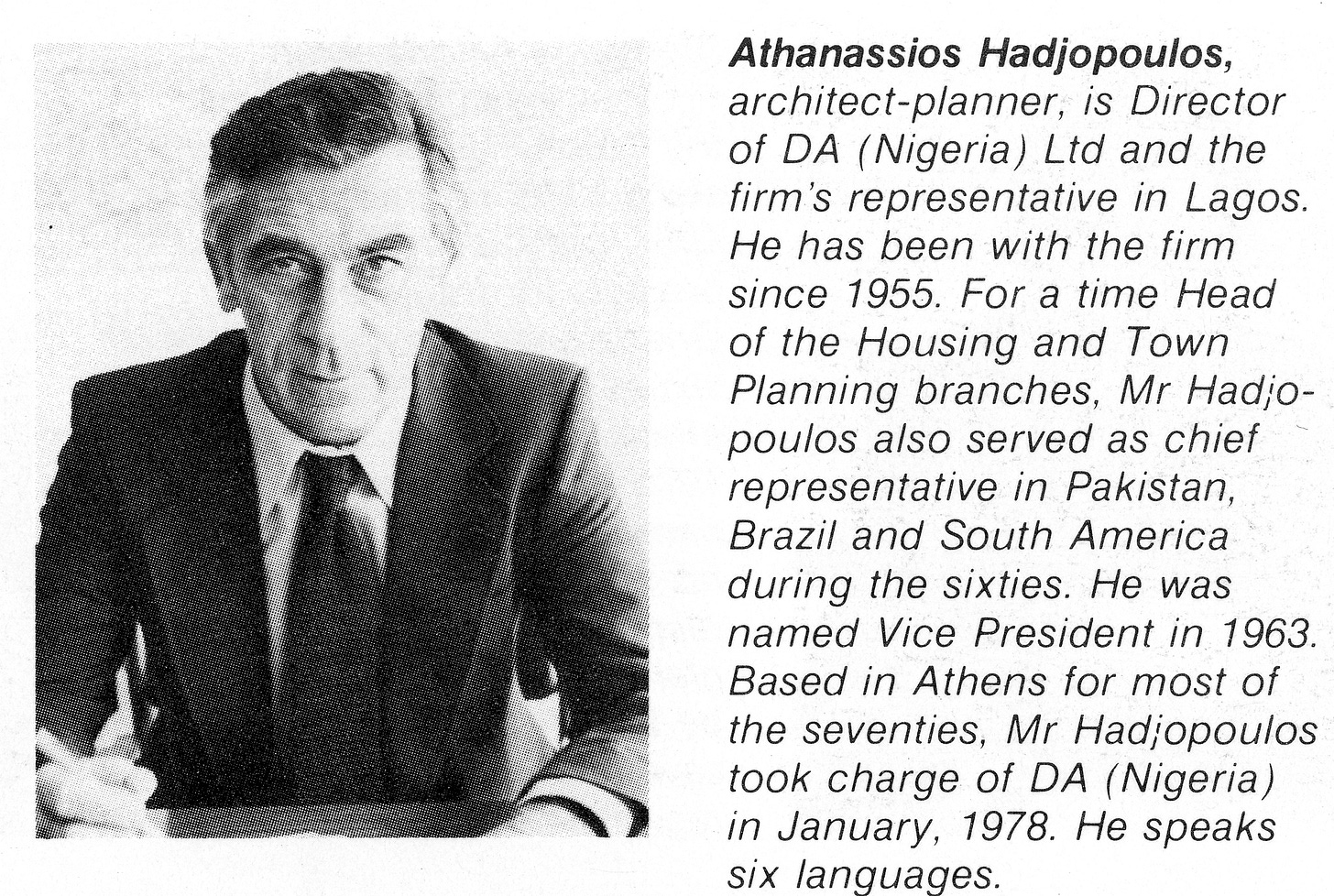

Hadjopoulos was 98. One of the reasons I had come all the way to Athens was to see him. I was glad I did, as the ensuing interview of Athanasios Hadjopoulos was astonishing in ways I could not have anticipated. As an eyewitness to some of twentieth century architecture’s biggest stars—Wright, Le Corbusier, Oscar Niemeyer, and Constantinos Doxiadis—Hadjopoulos possessed a unique perspective to evaluate these key figures and their competing priorities.

In the end, I was extremely fortunate to meet Hadjopoulos—after all, his time was running out.

Athanasios Hadjopoulos was born in 1919 in Faliro, a coastal community now part of the sprawling Athens metropolitan area. Hadjopoulos’ paternal grandfather was a professor of French in Istanbul and moved the family to Greece ahead of the Greco-Turkish war, in which Greece gained and lost territories in Asia Minor; the ensuing exchange of populations, mandated by the League of Nations, led to massive refugee crises in both countries.

As for Hadjopoulos’ father, he was the kind of man interested in everything mechanical; he had a habit of going into train stations and ducking his head under locomotives to see how they worked.

Some of that interest in engineering and systems must have rubbed off on Hadjopoulos. In 1939, Hadjopoulos entered the School of Architecture at the National Technical University of Athens. There he encountered Constantinos Doxiadis, assistant professor of town planning. The young, dashing, and ambitious Doxiadis recruited Hadjopoulos to his project cataloguing all the housing data of the Hellenic state. A year later, Italy, eager to start its own lightning war, attacked Greece; the Greeks repelled the Italian army but were quickly defeated when Germany came to Italy’s aid. Soon Hadjopoulos was a member of Doxiadis’ underground resistance group, collecting records of destruction, placing them in metal tubes, and hiding them in a cottage garden for retrieval by British Intelligence.

Thereafter, Hadjopoulos’ life, in his words, was the result of two phone calls. In 1945, he answered the phone to discover he had won a scholarship to study at the Sorbonne; in France, he later worked as an unpaid apprentice of Le Corbusier, the famed modernist. In 1955, Doxiadis, now a globetrotting architect with projects growing by the day—called him and asked whether he’d join his team in Iraq. Hadjopoulos said yes—and his life took on unforeseen directions and dimensions.

That was because he joined Doxiadis Associates (DA), Doxiadis’ massive urban planning firm based in Athens. During its peak period from 1955 to 1975, the firm worked on projects in more than 40 countries. Most known for designing Islamabad, the capital of Pakistan, DA also worked on notable projects in Nigeria, Brazil, Saudi Arabia, and the United States. In his native country, Doxiadis designed major sections of the Deree College campus, as well as an aluminum company town near Delphi. In that time, Doxiadis was a media star, appearing on Meet the Press, with profiles in The New Yorker and Life Magazine. Doxiadis also went on to found his own design philosophy, ekistics, the science of human settlements, along with a technical school, think tank, journal, and floating conference series on the Aegean to promote it.

But before all that took shape, Doxiadis Associates tackled a national housing program for Iraq’s twentysomething King Faisal II. Frank Lloyd Wright, on the other hand, was hired to build the Baghdad opera house. A year after Hadjopoulos’ encounter with the American architect, the king was assassinated and a sequence of revolutions ended Doxiadis and Wright’s involvement. Hadjopoulos’ brother, Nikolas, who also worked for the firm, was almost murdered by a mob if not for his Iraqi companion, who asserted Nikolas was Greek and thus more acceptable to a society justifiably frustrated with Western imperialism.

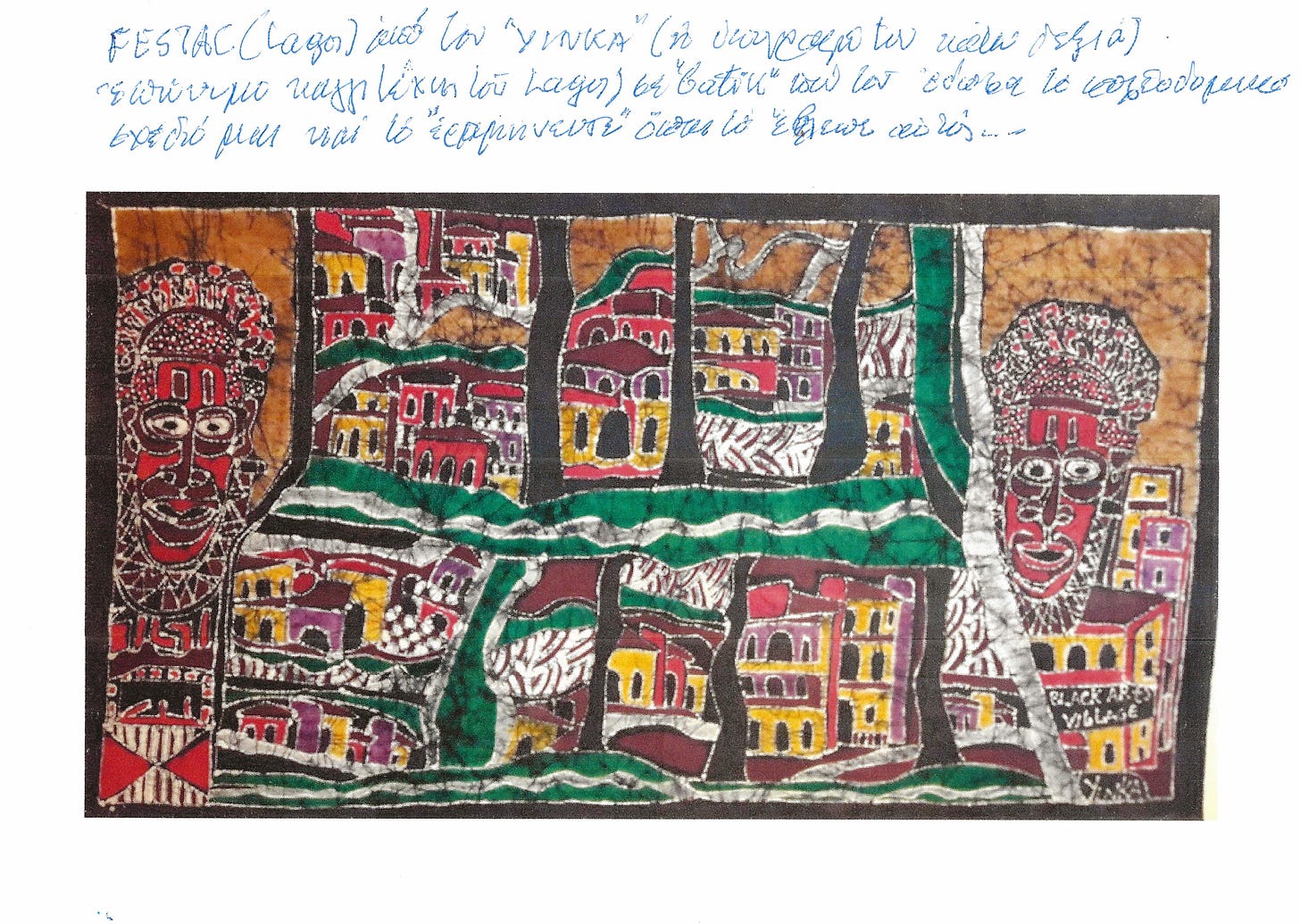

Much of Hadjopoulos’ later career with DA was spent in Brazil—where he became friends with Oscar Niemeyer, architect of Brasilia—and in Nigeria, where he was one of the designers of Festac, a new town built for the Festival of Black Arts.

Decades later, Hadjopoulos welcomed me into his home.

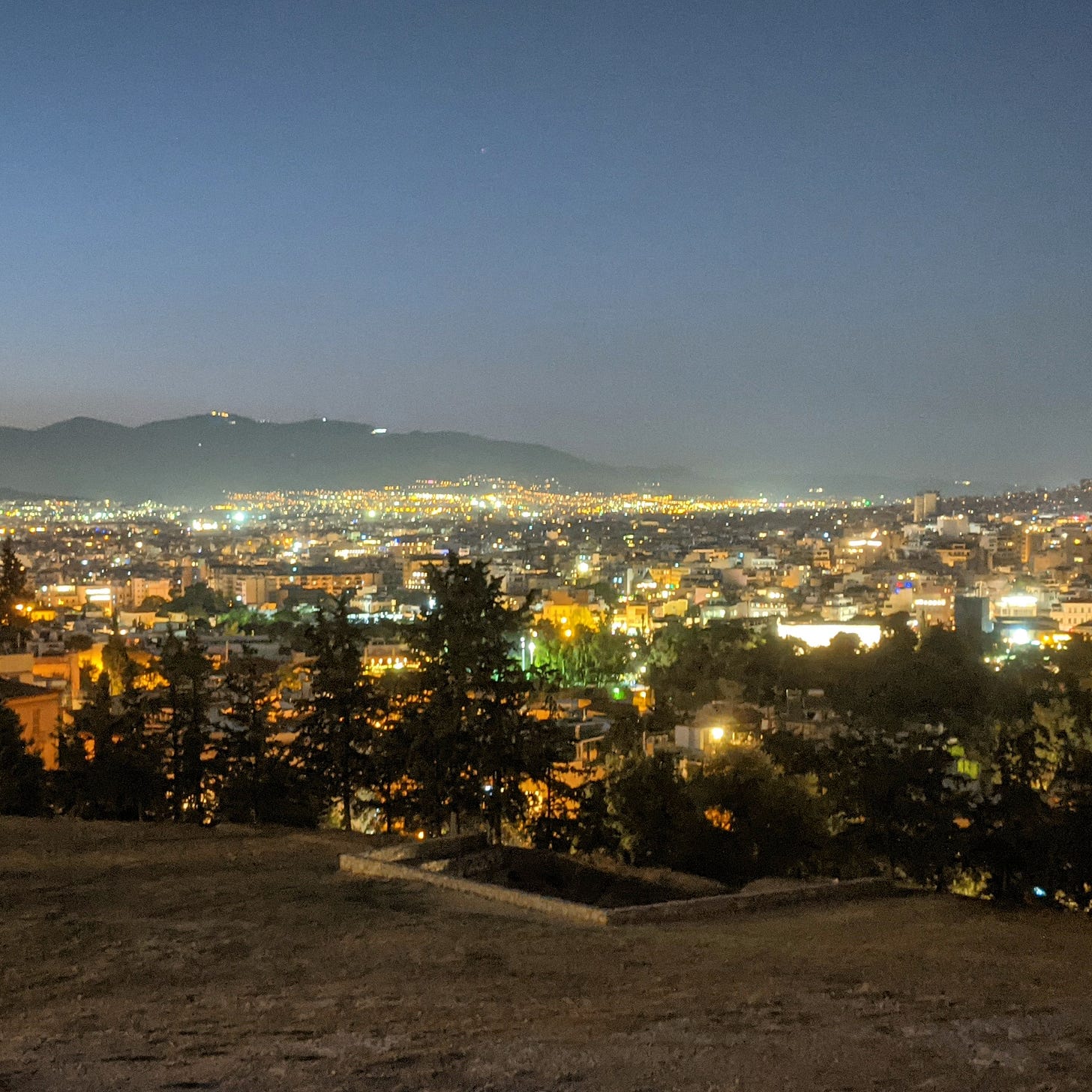

The house of Athanasios Hadjopoulos is in Peania, hometown of ancient statesman Demosthenes. Today, Peania is in the vicinity of Athens International Airport. In 2005, Hadjopoulos built the house for his wife, Odny, on a cliffside with a view of the airport so they would watch the planes come and go, to remind themselves of the travel they loved, a passion they could no longer pursue in old age. Odny had passed away in 2017—the pair had been married for 65 years.

“And a very good time, we had both,” Hadjopoulos said. “A marriage is successful when the two persons are different or complementary.” Interlocking his fingers, he explained that a husband and wife needed to adapt to each other—then you had strength. He took his hands apart. “Like this, you have nothing!”

I had come to Hadjopoulos’ house because of my interest in Doxiadis; I had been researching the life of the planner for several years to write a biography. And so I went to Greece in June 2018 for several Doxiadis-related reasons, but one of the most important was to see Hadjopoulos, who, at 98, was almost certainly near the end.

Indeed, Hadjopoulos’ body was in decline. Not long before my visit, he had fallen, and since then moved with the aid of a walker, in Greece called the “π” due to its similar shape to the Hellenic letter. He relied on the “π” until late in our interview, when he decided to leave it behind to walk around the kitchen—a reckless display which frightened me.

Despite his disability, Hadjopoulos’ mind was sharper than most people, of any age. The first question he asked was whether I was married. I was not. At that point, I was 23.

“You have to enjoy this decade from 20 to 30 and then there is time to marry,” Hadjopoulos said. “Not too late… I don’t think children would like to have a father who is old.”

“Right,” I said.

“You cannot even understand them!” Hadjopoulos said. “You cannot understand anyway…”

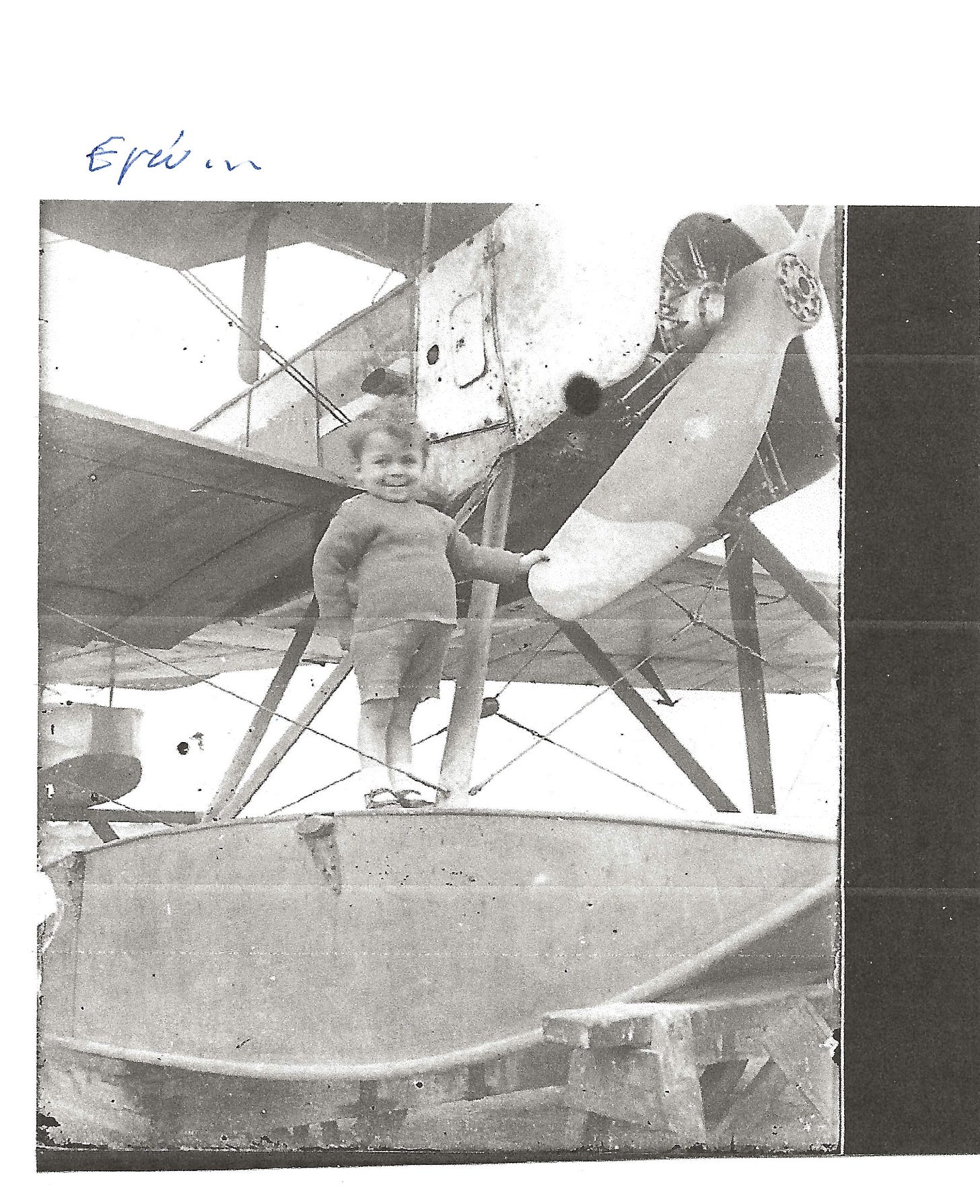

He led me to his office, where he showed me a photo of himself as a child. He was a cute little toddler standing on a pontoon seaplane, his hand holding the stationary propeller, a mischievous grin on his tiny face. When he was a kid, he said, his tinkering father had built one of the first radios in Athens, and when he turned it on for the first time, they mostly heard static—until, in the evening, music started piping in from Italy.

He then took me aback when he said he quite clearly remembered when Neville Chamberlain claimed to have successfully appeased Hitler by ceding to Germany Czechoslovakia’s region of the Sudetenland. “Things like this cannot happen today,” he said. “I think.”

He gave me his business card. In his mind, it was his current one. It read: ATHANASIOS HADJOPOULOS, MANAGING DIRECTOR, DOXIADIS ASSOCIATES (NIGERIA) LTD., VICTORIA ISLAND, LAGOS.

Before Nigeria, Hadjopoulos was stationed in Rio de Janeiro; Doxiadis Associates was then working on a plan for the Brazilian state of Guanabara. One day, a Soviet nuclear submarine made a visit to Rio. Guanabara’s Secretary of Education invited Hadjopoulos to attend an honorary event for the visiting Russians. A Brazilian official introducing the submarine commander added, “We have the pleasure and honor to have here Dr. Doxiadis.” Hadjopoulos was shocked—they couldn’t be referring to him, right? But the Secretary was insistent. She nudged Hadjopoulos. “Get up!”

Hadjopoulos confessed he could not admit the truth, not to the Brazilian official, and certainly not to the Soviet officer. So he went on with the charade.

“One thing that I learned all these years with Doxiadis is that nothing is isolated,” Hadjopoulos said. In his view, other architects, such as Wright, Le Corbusier, and Niemeyer— they designed beautiful buildings, but were uninterested in crafting sustainable systems of communities. For example, when Hadjopoulos worked for Le Corbusier, he was required to follow the golden ratio. Doxiadis, however, had the “Ekistics grid” as his design precept, a system of analyzing scalar levels of community, from a single room to the world-spanning ecumenopolis. “[The other architects] were not interested in this kind of problem,” Hadjoupoulos said.

Doxiadis’ views were evident in his design for Islamabad. Rather than focus on dazzling buildings at the expense of housing for the lower classes—as Niemeyer did in Brasilia— Doxiadis’ plan for the Pakistani capital conceived the city as a system of neighborhoods; he avoided flashy architecture and instead prioritized housing for lower-income groups. “When I say you cannot compare Doxiadis,” Hadjopoulos summarized, “[it’s] not that he is better—he is different!”

Soon, Hadjopoulos turned to more philosophical subjects. The height of the Greek classical period was around 500 B.C., he said, 2,500 years ago. And there are about four generations per century, each twenty-five years. Divide 2,500 years by twenty-five, and it seems we were just about a hundred generations from the golden age of Athens. “So, this Pericles, et cetera, was not very far as we believe,” Hadjopoulos said. “It’s nothing!”

Suddenly, an eerie feeling possessed me. A few days before, I had been standing on the ruins of the ancient road from Athens to Piraeus, and an old man came up to me and said the same thing—we were just a hundred generations from Pericles. We could take one person from each generation and fit them in a hotel ballroom.

Why did these two old Greeks perceive ancient Athens as such a recent occurrence? Was it merely a product of living so much of their life around ruins, or were they hitting on something we in the United States have forgotten? In North America, few reminders of antiquity remain—Ancestral Pueblo cliff dwellings, Mesoamerican pyramids. European conquest and genocide had erased so much cultural memory. Perhaps it took a near-centenarian to urge a return to perspective.

I blinked. I was exhausted. All this talk of history was wonderful, but this 98-year-old man was wearing me out!

The sun was low in the sky when Hadjopoulos asked when the book would be done. I was polite, but I knew I could not finish it in the near future, before he died. He told me he wanted to review the interview’s transcription for ‘misunderstandings.’ To this I agreed. Then he asked me, again, how old I was. I said I was 23. “I am four times as old as you,” he said, laughing.

As my driver took me back into Athens, I observed the neon gas stations along the way and marveled at the encounter I had just experienced. Who had I met? What had I witnessed?

When I returned to the States, I fell into a busy period, exacerbated by a cross-country move to begin graduate school. Weeks turned into months, and I had little time to transcribe the five-hour interview. Fearing the clock was ticking, I ultimately hired a friend to complete the task. By the time the transcript was complete, I needed two weeks to perform the final edits. Then I emailed the file to Hadjopoulos’ son to pass along for his father’s review.

His father would be unable to help. He had fallen the previous night and broken his hip. I was stunned. I knew it was coming, but when it finally came—I was stunned. The irony that I had finalized the transcript just as Hadjopoulos was injured seemed to evoke the poetic justice of classical drama.

Two weeks later, Hadjopoulos entered his eternal rest, after a lifetime of global activity.

In his life, he had met Frank Lloyd Wright, interacted with Oscar Niemeyer, and worked for both Le Corbusier and Doxiadis—perhaps four of the most important architects of the twentieth century. Some would argue that Hadjopoulos’ work for Doxiadis Associates brought sensitive design to low-income communities all over the world.

At the end of our interview, I asked Hadjopoulos if he could reflect on his life—after all, he had more time on this earth, and seen more of it, than most.

“Well, at the end of life, you always find things you should have done, and did not,” Hadjopoulos said, before remembering how much he missed his wife Odny. “Very often, I tell my head, as I am sitting here, believing that she is next [to me]… and I don’t like this house which was built too large for somebody, just as I am, to sit here alone.” Hadjopoulos paused. “On the other hand, I think that she did like very much the house and the veranda. In summer, we were sitting outside…” He trailed off. The sky was dark and it was becoming difficult to see the planes landing and taking off. My driver was waiting for me. Five hours had passed. My driver had his young son with him and needed to take him home.

Hadjopoulos’ daughter took our picture. He told me I was always welcome to come back and see him again. I told him I would try.

This is the second essay in a new series, The World Planner, chronicling my biographical investigations into the life and times of global architect and city planner Constantinos Doxiadis. These pieces take longer to write than the other posts, so they’ll appear on an occasional and quality-not-quantity basis. Keep up with the series on its homepage.